Double Jeopardy

Carlos Lavernia Spent 16 Years in Prison for a Crime He Did Not Commit. Should We Now Send Him Back to Cuba?

By Amy Smith, Fri., Feb. 23, 2001

"Please be advised that the subject is a Mariel Cuban and represents a particularly high risk for assault and escape."

-- INS internal memo on Carlos Lavernia, Dec. 27, 1984

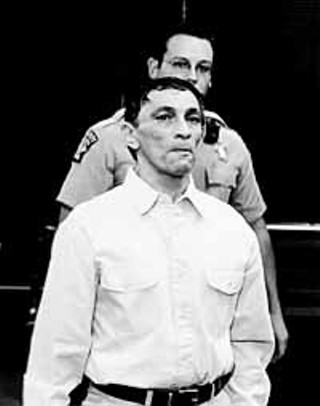

Carlos Lavernia may have considered himself lucky to be alive when he climbed aboard the big fishing boat that brought him to the United States from Cuba more than 20 years ago. But somewhere between his hassles with immigration officials and his dealings with the Austin Police Department, the exiled Cuban's luck went flat. Less than five years after coming to the U.S., he found himself on the judicial fast track to a prison cell in Texas. He was branded a serial rapist, suspected of a "sexually motivated" murder, convicted of sexual assault, and sentenced to 99 years -- all within a few months. Lavernia, it turns out, was a victim of the most common cause of wrongful convictions: eyewitness error.

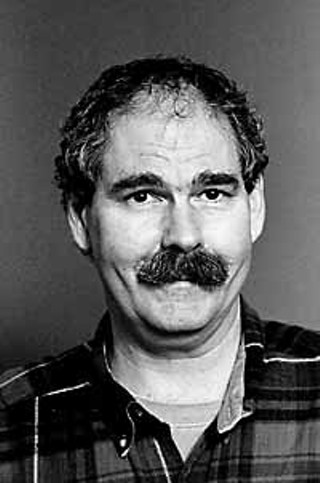

For nearly 16 years, Lavernia continued to proclaim his innocence from his cell in the Eastham Unit north of Huntsville, where he spent the first few months fearing for his life. Sex offenders, considered among the lowest of the low among inmates, are fresh meat when they come into the system. They are beaten, sometimes raped, by other inmates. "I tried to hide it," Lavernia says, "but everybody knows sooner or later why you're in the penitentiary." Lavernia, who is now 50 years old, points to scars atop his balding head, below his right ear, and on his forearm as evidence of the roughing up he received. Once, he said, he was attacked in the showers by another inmate brandishing a shank -- a homemade knife the prisoner had crafted from a spoon. The attacker -- from Austin's Montopolis area, according to Lavernia -- wanted to avenge his sister's rape. He stabbed Lavernia deep in the upper neck, just below his ear, coming within a hair's breadth of his carotid artery. Though Lavernia says it took him a month to recover from the shanking, Texas Dept. of Criminal Justice officials say they have no record of the incident.

On the other hand, they don't deny Lavernia's allegations, either, given the degree of gang activity and general bedlam in Texas prisons in the mid-Eighties, when the murder rate among inmates was at its peak. Eastham, where Lavernia did his time, was considered one of the wilder joints. "The inmates had the keys!" Lavernia exclaims, throwing up his hands incredulously. "They ran the place." These were, after all, troubling times for the Texas prison system. Officials were slowly, reluctantly, implementing reform measures laid out by U.S. District Judge William Wayne Justice in his landmark 1980 ruling in Ruiz v. Estelle, the class-action lawsuit brought by several hundred prisoners.

After his painful indoctrination into prison life, Lavernia hunkered down. He converted to Buddhism, which he credits for giving him resilience behind bars. He learned English and stayed out of trouble. With nothing but time on his side, Lavernia enlisted the aid of self-taught jailhouse lawyers to help him begin his mission of drafting several years' worth of letters and writs he hoped would someday clear him of the conviction.

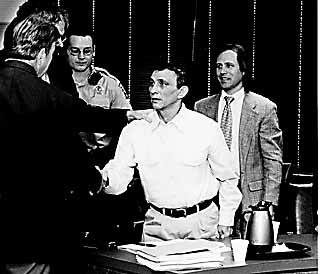

And though it might not have been his prison writ-writing that freed Carlos Lavernia, last year he was cleared of the crime that put him away for 16 years. The Travis County district attorney, whose office had prosecuted Carlos Lavernia, announced his innocence. Just two months before the November election, D.A. Ronnie Earle, who was seeking his seventh term in office, came forward with some startling news: DNA testing had borne out Lavernia's assertions that he was not the "Barton Creek rapist" who had terrorized women hikers and joggers between 1981 and 1983. At the same time, Lavernia was eliminated as a suspect in the March 1983 murder of a woman whose body was found in the greenbelt. "He needs to be out of prison," Earle told reporters at the time. "It's a terrible tragedy for him."

Under most other circumstances, Lavernia would have walked by now. Though the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals set aside his conviction in late November, another barrier stands between Lavernia and the free world -- the Immigration and Naturalization Service. While Lavernia is out of state custody, he remains in the Travis County jail while the INS weighs his fate. A team of lawyers are donating their time in an attempt to free him, and the immigration lawyer on the team has requested a hearing before an immigration judge in San Antonio. If granted the hearing, Lavernia's attorneys will argue that their client deserves a chance to return to society a free man.

This isn't Lavernia's first encounter with the INS. The federal agency, in fact, had already taken Lavernia into custody nine months before police suspected him in the Barton Creek rape case. In 1982, not long after Lavernia and his new wife and her children had settled into a trailer home in Lockhart, he was accused of exposing himself to a nine-year-old girl in South Austin. He pleaded guilty to the charge, a third-degree felony, and was placed on probation for 10 years. At the time he entered the plea, neither Lavernia's attorney nor the judge warned him that the offense was considered an excludable, or deportable, offense in the eyes of the INS, an agency known for being especially hard on Marielitos -- Cubans who migrated to the U.S. in the massive 1980 boatlift out of the country's Port of Mariel. Of the 125,000 Marielitos who came here on the so-called Freedom Flotilla, about 1,700 remain in "indefinite detention" -- sort of an INS version of the Bermuda Triangle. Diplomatic relations are nonexistent between the U.S. and Cuba, which usually doesn't allow the repatriation of its nationals. So these deportable or excludable "Cuban lifers," as they are called in the county jails where the INS rents space to house them, serve a second sentence after they have paid their debt to society. A small number go home: A 1984 immigration pact with Cuba gives the U.S. some deportation privileges. Last year, the INS returned 82 Cubans, 70 of whom had criminal convictions.

Lavernia's pro bono attorneys -- immigration lawyer Karen Crawford and criminal defense lawyers Chip Waldron and Bill Allison -- are trying to win Lavernia the freedom they say he deserves. "This poor guy has lost everything," says Waldron. "He needs to get his life back." The ultimate goal, adds Crawford, who earlier this month hand-delivered a motion to the INS district office in San Antonio, is to convince an immigration judge to grant Lavernia asylum -- or at least permanent residency -- in the U.S. His 27-year-old stepdaughter, Rosalinda Longoria, who lent moral support to Lavernia throughout his incarceration, is prepared to take him into her home and help him start a new life (his wife divorced him while he was in prison). "In every letter he wrote me from prison," Longoria says, "he always said he was innocent and that he would prove it someday." A skilled cook, craftsman, and carpenter, Lavernia shouldn't have any trouble finding employment, Crawford says.

The sticking point in securing Lavernia's freedom is his 1982 conviction. While acknowledging that an indecency case involving a child is not as forgivable as, say, a shoplifting offense, Lavernia's lawyers argue that their client has paid his debt to society many times over. Not mentioned in the Chronicle's interviews with the lawyers is the fact that if Carlos Lavernia had been born in Austin, New Orleans, Newark, or anywhere in the U.S. he would today be free to go about the work of rebuilding a life destroyed by a wrongful prosecution. "Prejudice and poor advice -- or no advice at all -- have all but destroyed Mr. Lavernia's life," Crawford wrote in her INS motion, which makes an impassioned plea for her client's release.

The document also provides a historical account of Lavernia's hardships, both in the United States and in Cuba, where in the late Seventies he was a political prisoner of Fidel Castro's regime. Lavernia says he joined the Cuban army as a teenager because he was excited about the prospects of the revolution. Years later, he says, he grew disillusioned with communism and tried to leave the army. He was sentenced to three years -- two in prison and one on probation -- for treason. "Castro likes to play with your mind," Lavernia says matter-of-factly, sitting in a small cinderblock room at Travis County's Correctional Complex in Del Valle. He went on to explain how in prison he was placed alternately in hot and cold cells as a method of punishment, and fed only two meals a day. After his release, Lavernia took a job as a cook at a beachside motel, but it wasn't long before state security officers showed up at his workplace and gave him 24 hours to leave the country on the boatlift. According to the motion before the INS, "Castro warned [Lavernia] and others who had left the army as a matter of conscience that they would be killed if they were ever to return." The legal document goes on to enumerate nearly every wrong ever inflicted upon Lavernia. "We want to look beyond the legal facts of this case and appeal to emotions," explains Crawford, the former legal director of the Political Asylum Project of Austin, a nonprofit group that provides services to low-income immigrants. "Humanitarian reasons are the most compelling reasons why Carlos should be released."

How this humanitarian argument will play before an immigration judge, assuming that Lavernia is granted a hearing, is something of a crapshoot. "Immigration law judges," explained district spokesman Denton Lankford, "are fair and impartial, and I want to emphasize the word 'impartial.'" He was quick to add that the INS doesn't look favorably on undocumented aliens who run afoul of this country's laws. Lavernia, he says, "does have a criminal history." Before he was charged with indecency, Lavernia had some prior scrapes with Austin police, though they didn't amount to much. The INS, however, doesn't discount those run-ins with police. In one, Lavernia was busted for breaking into a car at Auditorium Shores, but the charge was dropped when he copped a plea on the indecency indictment. In another incident, Barton Springs Pool employees complained to police that Lavernia had exposed himself to pool patrons. By the time the police showed up, though, the witnesses had gone home, and nothing ever came of the matter.

"Barton Creek rapist sentenced after quick conviction" -- Austin American-Statesman headline, January 1985

Late on the afternoon of June 2, 1983, a 24-year-old woman set out on her daily walk through the Barton Creek Greenbelt -- and returned home a victim of a terrifying assault that turned her life upside down. Until the rape, the native Austinite, who is not identified here to protect her privacy, considered herself fortunate to live in an apartment so close to the greenbelt, where she had only to go a short distance to enjoy the sanctuary of the rich green wilderness that spread for miles before her. When she testified at Lavernia's rape trial a year and a half later, the woman described the day as beautiful, warm, and sunny, as she headed east from her apartment on Spyglass Drive toward Gus Fruh Park. She crossed a rock bridge held together by chicken wire and headed out on a dirt trail alongside the creek, which veered eastward for a ways before continuing its flow south. She walked for another 150 yards when she saw a man heading westbound in the opposite direction. He was Hispanic, she would later tell police, with a dark complexion, about 5'6", in his early to mid-20s. He was wearing a maroon shirt and baggy maroon polyester pants. The two passed each other without speaking.

The woman walked along the trail for another half mile, then turned around to head back home. Out of nowhere, the man fell into step behind her. "I thought I just passed you going the other way," the woman said, picking up her pace. "Why are you walking so fast?" the man responded, before grabbing her from behind and pressing a knife to her throat. She pleaded with him to take her jewelry and her watch. "You know what I want," he replied, and dragged her off the trail, where he forced her to perform oral sex, then placed her on her hands and knees, struck her on the back of the head, and sexually assaulted her. When the ordeal ended, the woman testified that she let loose with a string of obscenities, hoping to scare off her attacker and attract the attention of other hikers. The man ran off, heading east and carrying the knife. Frantic, the woman pulled on her pink jogging shorts and ran for about a quarter of a mile before she spotted a sunbather, a UT student from Houston, who escorted her back to her apartment where the two called police.

It was the sixth rape along Barton Creek in two years, all with the same M.O. -- which involved the suspects threatening the victims with a knife. Only three months earlier, a Johnson City artist, Sally Tullos, was found stabbed to death in the same area. Police suspected a link between her murder and the series of rapes.

Details of the June 1983 rape were gleaned from police reports, newspaper clippings, and a transcript of the one-day trial. The Chronicle made several attempts to contact the victim through the district attorney's office, but she apparently did not respond to phone messages. Assistant District Attorney Bryan Case, director of the appellate division, said the woman is understandably distraught on two counts: sending the wrong man to prison, and living in fear that the attacker could strike again. After learning of the DNA results last fall, the woman told the Austin American-Statesman: "I pretty much want to crawl into a fetal position and go away." Her life wasn't any more peaceful before the DNA test, however. According to an Oct. 11 account in the Statesman, the victim said she moved out of Austin after the assault, and developed physical symptoms related to the stress and emotional trauma.

For Mike Cox, a veteran cop reporter for the Statesman at the time Lavernia was convicted, the Barton Creek rapist story was just one of several high-profile crime stories he filed for the afternoon paper, back when the daily published morning and evening editions. At the time, Cox recalls, newspapers generally placed more emphasis on crime news, so there was more incentive for reporters to ferret out a juicy banner headline story for the "bulldog" -- the early press run geared toward street sales and newsstands. "Austin hasn't been a sleepy little college town since the Fifties or early Sixties," said Cox, an author, longtime spokesman for the Department of Public Safety, and now director of member services for the Texas Press Association. "I wrote a jillion rape stories," Cox recalled of his early newspaper days, "and any time someone is prowling a public area and preying on women, the story has significant local interest. But did the Barton Creek rapist case paralyze the city? I think it would be overbroad to say that it did."

A seventh rape followed the June 2 attack, and then the attacks stopped cold. In the last incident, the victim gave police a decidedly different description of her attacker; he wielded a knife, as in the other assaults, but this one stood 5'10" -- several inches taller than the suspect described by previous victims -- and had dark, wavy hair, as opposed to earlier reports that the suspect had straight hair. Despite these discrepancies in the two assaults, Lavernia was charged with both rapes, but he only stood trial for the June 2 incident.

The height differences, among other things, "should have been a clue to us," said Assistant D.A. Case, who, while he did not prosecute the case, recalls certain details of the trial and the sometimes overblown news accounts of the Barton Creek rapist. "In reality," Case says, "there were only three completed sexual assaults, four attempts, and one murder." He now believes it wasn't just one perpetrator who committed the crimes.

Looking back, Case is today as perplexed as anyone in trying to understand how Lavernia could have possibly fit the description of the attacker. One of the first things one notices about Lavernia is that he's short. Police records peg him at 5'4", but 5'3" seems to be more accurate, as Case agrees. Plus, the prosecutor says, Lavernia had other well-defined features -- tattoos on both arms and a silver star in his tooth. Another glaring discrepancy centered on Lavernia's inability to speak English, requiring an interpreter to sit beside him at the defense table. Even now, when Lavernia repeats the question the Barton Creek rapist asked on June 2, 1983 -- "Why are you walking so fast?" -- the words are heavily accented, yet police reports never mention the suspect's distinct accent.

Additionally, it appears that the victim only noticed the suspect for a few seconds, when she passed him on the trail the first time. According to the offense report filed by the investigating officer: "She closed her eyes when he first put the knife to her throat and kept them closed. She told him she had her eyes closed and didn't want to see what he looked like and didn't want to see him again. She told me that she said this because she was afraid he was going to kill her and she wanted him to think she hadn't seen him."

"All those things were explained away," Case reflected recently. "In hindsight, we should have said, 'He's not the guy.'" How, then, did Lavernia become "the guy" that jurors were so quick to convict? There are a few reasons. First of all, Lavernia frequented Zilker Park, sometimes with his family and sometimes alone, so police, by now familiar with him, singled him out for questioning a few times during their investigation. In August of 1984, an Austin police investigator was sifting through some old dispositions on felony cases, when he came across Lavernia's indecency case and noticed that his photograph resembled a composite drawing of the rape suspect. The investigator, figuring that the INS had already deported Lavernia due to the indecency conviction, began rather hastily connecting the dots. "It also occurred to me that we [APD sex crimes division] had earlier in the summer discussed that the rapist had either been sent to prison for something else or moved away from the Austin area, thus accounting for no new cases this summer," the investigator wrote in his narrative. He added: "Carlos did fit in this category."

As it happened, Lavernia had not been deported, but was in INS custody in Atlanta, so he fit neatly into the theory the sex crimes division had developed about the identity of the Barton Creek rapist. While police filed the necessary paperwork to have Lavernia transferred to their custody, investigators assembled a photo lineup of suspects and tossed Lavernia's mug into the mix. It was the third time the woman had reviewed a photo lineup. This time, she picked out Lavernia immediately. As it happened, the other suspects in the lineup looked absolutely nothing like the composite drawing, while Lavernia, as the woman herself testified, was the only one who "anywhere near resembles" the drawing.

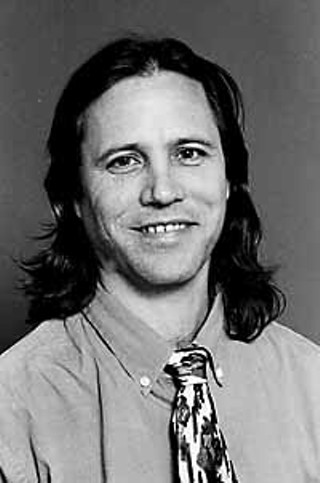

"The inherent psychology in photo lineups is that the eyewitness is trying hard to find the person who most resembles the suspect," explains criminal defense attorney Bill Allison, one of Lavernia's three lawyers. "We've always known anecdotally, and scientifically, that eyewitness identification is shaky, and yet it is a bedrock of criminal prosecution," he says. An eyewitness who is also a victim makes the case that much more problematic, particularly if the case is built solely on the victim's identification, as was Lavernia's case. "Here you have a genuine victim and you want to believe the victim, who has been hurt and traumatized," Allison says. When the victim turns to the defendant in the courtroom and identifies him as the perpetrator, he adds, the jurors are in a serious hold. "It's very, very powerful."

And in some cases very destructive. In a June 2000 op-ed piece in The New York Times, Jennifer Thompson, who was sexually assaulted in 1984, wrote about her own experience of identifying the wrong suspect. She identified her attacker in both a photo lineup and a live lineup, and also in the courtroom when the case went to trial in 1986, where the man, Ronald Cotton, received a life sentence. The case was retried a year later because another man had bragged that he was the actual rapist. But, Thompson wrote, she was absolutely certain she had identified the right man the first time, so Cotton was again convicted and sent to prison. Eleven years later, a DNA test proved that he was not the rapist. Her attacker was the man who had boasted of his deed in the first place. "If anything good can come out of what Ronald Cotton suffered because of my limitations as a human being," Thompson wrote, "let it be an awareness of the fact that eyewitnesses can and do make mistakes." Last summer, Thompson came to Texas to try to convince Gov. George W. Bush and the Board of Pardons and Paroles not to execute Gary Graham, who was to be put to death based on the account of one eyewitness. They listened, but Graham was put to death anyway.

Apart from the identification error, Case believes Lavernia was his own worst enemy in the courtroom. During the trial, he couldn't hide his anger over being wrongly accused, and jurors interpreted his anger as something more sinister. When Case recently called the jurors to inform them of the DNA test results that got Lavernia out of the state's prison system, Lavernia's harsh demeanor still stood out in the jurors' minds. "I personally talked to about five of them," Case says, "and what they remembered was how he glared at the victim. And, of course, he wasn't guilty, but the jurors -- they're there taking everything in. They just didn't like him. They positively didn't like him."

"Sally Tullos, a Johnson City nature lover slain as she walked along Barton Creek, may have been the latest victim of a man responsible for raping six women along the creek in the past two years." -- Austin American-Statesman, March 3, 1983

In the end, persistent police work and the profession's obsessions with cold cases had far more to do with Lavernia's exoneration than did the letters and writs he wrote from a TDCJ prison cell. In the fall of 1999, more than 16 years after the crime, Austin police Detective J.W. Thompson began looking at Lavernia as a suspect in the 1983 death of Sally Tullos, the woman whose murder had been linked to the Barton Creek rapist. Tullos' attacker had delivered a single stab wound to her neck, covered her up with brush, and then left her to die on a dirt trail between Barton Springs Pool and Campbell's Hole. Thompson took a DNA sample from Lavernia, which eliminated him as a suspect in the case. Lavernia told him that another DNA sample would also clear him of his rape conviction. Thompson could not ignore the ring of certainty in Lavernia's voice. The police officer ran the request by Assistant D.A. Case, who thought it would be worth a try.

But he knew that because the case was 16 years old, locating the evidence would be tough. "I checked out our evidence room at the police department and there was no evidence," Case recalled. A check of the district clerk's office turned up empty as well. By now, Case and Thompson were ready to give up on the search, and had discussed writing Lavernia a letter to inform him that the evidence had disappeared. But as a last resort, the two decided to search an old warehouse where they found what little evidence there was crammed into a single manila envelope. Inside were the victim's jogging shorts, a rape kit, and a blood sample. "Neither one of us thought that it was going to come back clearing him," Case said. He drew up a motion seeking the DNA test; a sample was collected and sent to the DPS lab. On Sept. 8 of last year, Case got the call. "They said, 'he's excluded,' and I'm going, what? I was completely shocked. He's a lucky fellow, I guess."

Other Texas inmates might soon be equally lucky. Police and prosecutors, chagrined over the serious errors that caused Lavernia to lose 16 years of his life, are committed to reviewing hundreds of post-conviction cases involving rape and murder, to determine whether others had fallen through the cracks. They've reviewed about 100 cases so far, with about 300 left to go. Shortly after Lavernia's DNA results were announced, another piece of startling news followed, this time based on the work of the Wisconsin Innocence Project: A DNA test conducted on Christopher Ochoa, one of two men convicted in Travis County and serving a life sentence for murder, showed no connection between Ochoa and the crime scene of the rape and murder of a Pizza Hut worker in 1988. These stories, of innocent men serving decades of jail time for crimes they didn't commit, have influenced legislators, and this session several DNA bills have been filed in the Texas Legislature (see "New Forensics, New Laws," below).

Mark Gillespie, director of forensics for the Austin Police Department, can't say enough about the wonders of DNA. "It is one of the best investigative tools available to us," he says. APD's reliance on the Department of Public Safety lab for DNA testing will soon be a thing of the past, Gillespie adds, because the department is establishing its own lab to conduct any number of tests. "I believe we should use the available techniques as often as we can," he says, "regardless of whether it's a low-profile or a high-profile case."

"The only part of 'due process' Mr. Lavernia has known is 'process' -- he has been quickly and expeditiously 'processed,' to his detriment." -- Motion to reopen Lavernia's INS case, February 2001

When Austin attorney D'Ann Johnson first read the news report that a DNA test had cleared the way for Lavernia's exoneration, she knew that another set of legal problems awaited him. "I saw the story and I thought, 'This guy's going to have problems.'" Johnson should know. She has represented a number of INS detainees and understands the difficulty of dealing with the INS bureaucracy. As the executive director of the Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association, Johnson also knew she wouldn't have time to take on a case like Lavernia's. So she called on lawyer Chip Waldron, who speaks fluent Spanish, to do the job. Soon Bill Allison and Karen Crawford, who also speaks Spanish, were on Lavernia's defense team as well. Together the trio has spent more than 100 volunteer hours on the case. "Some days, I think we can really win this, and other days it's like hitting a brick wall," Crawford said.

If worse comes to worse, Lavernia reasons, he would rather spend the rest of his life in a U.S. prison than return to Cuba. Should he be deported, Lavernia -- like other exiled Cubans -- genuinely believes that Fidel Castro would order him killed. "Like that," Lavernia said with a quick snap of his fingers. "Like that," he snapped again.

"I rather die over here." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.