Defining the Name of the World

Denis Johnson's Latest Novel

By Clay Smith, Fri., July 7, 2000

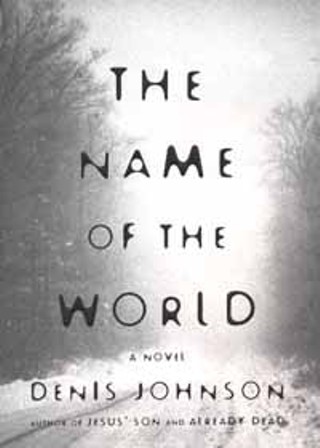

The Name of the World

by Denis JohnsonHarperCollins, 129 pp., $23

Quite early in Denis Johnson's new novel, the narrator observes that "people I hardly knew often suggested, one way or another, that they'd like to help me." Then he explains why. He used to work for a senator: "I was the object of much goodwill, in fact, sometimes because the man I'd worked for in Washington was disliked, and I'd quit him; or, conversely, because he was liked, and I'd worked for him." It wouldn't be fair to call Michael Reed, the narrator, a liar, but soon enough it becomes clear that his explanation is just the convenient, palatable truth. We're not getting the entire story.

Later, he comes right out with it. "People gave me gifts, people liked me, maybe because they sensed I was virtually dead and couldn't hurt them." In Jesus' Son (see related Screens story), Johnson's beloved short story collection, the narrator of "Car Crash While Hitchhiking" acknowledges "not caring whether I lived or died." The title of Johnson's previous novel, Already Dead, comes about because a character has looked himself over and decided that he is "already dead." Already, virtually dead: Johnson likes to situate his characters on the brink of that all-important precipice. Anyone who hasn't done battle with their demons and come out the other side can enter Denis Johnson's world and get a lesson. Those who have will certainly find some understanding.

As for Michael Reed, he feels virtually dead because his wife and daughter are absolutely, positively, and quite suddenly dead. His wife "wore the world lightly, and that was important to me," he confesses. "I didn't think often about that which people called God," he states in one of the blackest moments of the book, "but for some time now I'd certainly hated it, this killer, this perpetrator, in whose blank silver eyes nobody was too insignificant, too unremarkable, too innocent and too small to be overlooked in the parceling out of tragedy." Some time before the present action of the story, the narrator was a high school teacher who decided to write a letter to Sen. Thomas Thom advising him on policy and strategy. Thus he went from being "Mr. Reed the Social Studies person" to "Mike Reed the speechwriter, staff floater, and cloakroom confidant." Reed was able to hang on with the senator until the beginning of his fifth term, when he resigns and begins to think about writing a book that would "witness to power's corrupting influence." "But apparently no such witness was required," he concludes. So he is grateful when offered a position at a university in the Midwest teaching history in small seminars with books he has already read. He likes to think of his time at the university as a "vacation," and he tries to figure out how to extend it, even though four years is the typical extent of the type of position he occupies. He has time to make his own prescient observations about doing battle with your demons:

I like being around people who like being where they are. In the scholarly world, the world of the mind, much more than in the world of politics, it's common to meet people who've truly earned their comfort, at least in a sense, having labored through and left behind parts of childhood so unpleasant for scholars, brains, intellectuals. And here they are, respected and safe at last, while the others slug it out in the marketplace.

Nearly four years after the death of the narrator's family, its sole survivor is taking stock of his surroundings and ruminating, with some time on his hands. There's a muted quality to what he has to say, as if he's been sucked dry. In many ways, The Name of the World seems like the story Melville's Bartleby the scrivener would have told if he weren't so crippled, unable to speak and unable to let us in on his deterioration. Reed's observation above is really quite insightful and in direct opposition to a common notion of academics, which is that they are buffoonish, priveleged, and unworldly people. But what he has to say about them doesn't call attention to itself; it's not grandiose. He writes as if he were just another reporter typing about the incidents at hand.

The paralysis of grief does that to a person, but grief through a poet's eyes isn't grief unadulterated. Grief, to become a story, must have something extra thrown into the mix, so while Reed tends to report the facts, he also knows how to make his confessions quite lush and adventurous. He can also be funny. On meeting a historian from the art department: "A friendly but awkward woman, precise and despairing -- a homely woman, and I think I have the license to make such a remark, because I'm homely, too, and older than she, so I was homely first." Fans of Johnson's tendency to force his characters to hover over the edge of madness, like Gogol but without all the mania, will be heartened by several passages in the book, one of which has Reed visiting a colleague at the university's Forum for Interpretive Scholarship, which is adjacent to a Head Trauma Rehabilitation Unit. People wearing "open galoshes and pajamas under overcoats" are "practicing simple movements with rehabilitated heads":

Just such a person as I've described blocked our path -- a smiling man with one hand raised high above his head -- and said to me, "I'd like to give you my address."

J.J. spoke up and said, "That's fine. But do we need your address?"

The man leaned unsteadily to one side as if fighting a strong wind, his left hand raised and the fingers curled around an imaginary baton, or a small invisible torch. "I'd like to give you my address."

"Okay," I said. "Go ahead, if you want."

"I'd like to give you my address," the man said. "I'd like to give you my address."

Reed seems to be quite decided about how his story should be meted out. Near the end of the book he spends an unsettling day with a student from the university who's a performance artist. He's basically infatuated with her. They're sitting on the grass outside her home when she asks for a sample of his handwriting. This seems quite freaky to him. "I'm not sure," he says. She presses on; she really wants some of his handwriting. "Here I felt our movement toward the unforeseen," he reflects, "in the direction of something that couldn't have been predicted. I don't think I'll try to explain what I mean by that." The refusal to explain magnifies the seeming aimlessness of the journey -- part wanderlust mixed with stunned confusion -- until the journey itself is the story. Moving toward the unforeseen is really the only direction the narrator can take. The Name of the World is poetry that happens to be packaged as prose, so it's not unnatural that the crucial elements of a novel, like where and when it takes place, begin to matter less and less as the story progresses. It's not so important that the book takes place in the Midwest -- this isn't a story about the astringent paranoia of the Midwest -- and it becomes less important that the narrator teaches at a university. The story is larger than a treatise on how debilitating the confines of the academic life can be. Reed says he wants his story to be "luminous images, summoned and dismissed in a flowing vagueness."

Grief is just the "flowing vagueness" part. This story's luminous images come about from battling the befuddlement that grief imparts. The Name of the World is grief told anew, as if we hadn't really known anything about it before. Johnson's typical clarity is in powerful focus here. It's a minute and sometimes wrenching focus that somehow seems to encompass the entire world. ![]()