Book Reviews

By Cyrus Cassells, Fri., Oct. 29, 1999

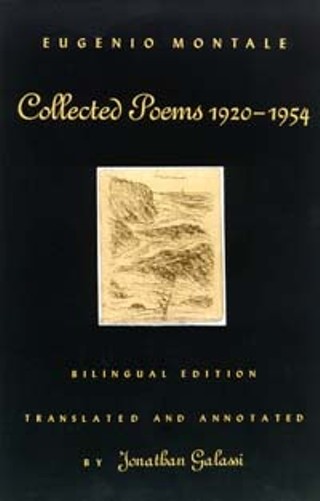

Collected Poems 1920-1954

by Eugenio Montale

translated by Jonathan Galassi

Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 600 pp., $40

For lovers of poetry and Italian literature, Jonathan Galassi's elegant, admirable translations of the Nobel Laureate Eugenio Montale's first three classic volumes, gathered together in Collected Poems 1920-1954, comes as an indispensable, welcome gift, especially since the glimmering, supple, elementary poems of Montale (who lived from 1896-1981) have had a far-reaching impact on contemporary world poetry. Alongside Galassi's astute and sensitive translations, he has also included an insightful essay, "Reading Montale," a helpful chronology, and fascinating, voluminous notes that make it apparent that this masterly collection is a labor of love and dedicated scholarship.Part of Montale's genius in Italian is his signature going against the grain of Italian's innate musicality and emotionality -- there's friction in almost every nuance, every line -- and Galassi goes a long way toward capturing in accessible English some of the crisp, astringent quality of Montale's verse, the dissonance that suggests an anguished, modernist sensibility, particularly in the terser poems of The Storm, Etc.:

The wind picks up, the dark is torn to shreds,

the shadow that you send out on the fragile

balustrade is curling. Too late, if

you want to be yourself! The mouse

drops from the palm, the lightning's on the fuse,

on the long, long lashes of your look.

In the essay, I found particularly useful Galassi's discussion of the power of objects in Montale's poetry; an eel, a lily in a ditch, a twig jutting "like the needle of a sundial," are a few of the objects hallowed by the poet's attention, his rich cataloging that "becomes ever more extravagant and surprising, a constantly transforming series of metaphors spiraling toward an elusive core." Galassi also notes how Montale's quicksilver poetry, so rife with metaphysical and philosophical flourishes, keeps returning to key objects, reassessing them over time, as if they had not yet "betrayed their final secret." The American poet Stanley Kunitz has remarked how each poet has a cache of potent central images rooted in earliest experience that forms the poet's vocabulary: this seems exceptionally true of Montale, whose alphabet of sea, wind, walls, cicadas, storms, mists, and flight is rooted in a youth spent in the renowned Cinque Terre region of the Tuscan coast.

Reading Montale is like reading the restless poetry of a whirling dervish (without the blissful tone) -- everything is in constant motion in his world, and yet there's a paradoxical stillness at the core. The poems are vivid and extremely sensous, yet airy, in flux -- a rich and unusual combination. In the context of Italian culture's deep-seated fidelity to home, family bonds, and security, Montale's questing, untethered spirit seems especially distinctive: an intriguing anomaly.

The effect, for my part, after reading a succession of Montale's poems, is a faint feeling of vertigo, which is what you might expect from a vision that suggests life as if seen from a swift train. In fact, two of my favorite Montale poems are "Local Train" and the following poem:

From the Train

The blood-red turtledoves

are at Sesto Calende for the first time

in human memory. So the papers say.

I've hung out the window, hunting them in vain.

One of your necklaces, another color, true,

bent down a reed and unbeaded.

It flashed for me alone, then fell in a pond.

And its flight of fire

left me blind to the other.

Cyrus Cassells teaches creative writing at Southwest Texas State University and is the author of three collections of poetry, the most recent of which is Beautiful Signor.

The Michener Center for Writers hosts Jonathan Galassi tonight, Thursday, October 28 at 7:30pm in the fourth floor auditorium at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center (21st & Guadalupe).