The Sound and the Fury

The Alamo Drafthouse's Silent Film Series

By Jerry Renshaw, Fri., Sept. 10, 1999

The house lights are still up as the crowd files into a feed store hastily converted into a movie theater. As people find their seats, the pianist takes his place behind a big, black Baldwin and carefully arranges the stack of sheet music on the piano's music stand. A din rises from the audience as they wait restlessly. At last, the house lights dim and the crowd becomes quiet. The first flickering images appear onscreen, and after the applause dies down, the pianist begins playing a tinny melody. The score being played, written to complement the film scene by scene, is not an intrusion, but rather an integral part of the film experience for this 1911 audience, setting mood and atmosphere, and enhancing the emotional content of the movie. Sounds quaint, doesn't it? Like something that went out of style along with handlebar mustaches and high-button shoes, a bygone ritual that goes with Iowa church ice cream socials, barbershop quartets, and evening concerts in the park where gentlemen ride around on high-wheel bicycles. Certainly all are from the same era, an era that saw Paris audiences dive under their seats when the Lumiere brothers debuted the first films of trains barreling into the station. Ditto for the opening shots of The Great Train Robbery, in which a mustached bandit levels a cap-and-ball Colt six-gun at the camera and fires away at audiences who initially ducked from the hail of imaginary bullets. Call it a primitive, turn-of-the-century equivalent to the IMAX experience. When Al Jolson's The Jazz Singer came along in 1927, that all changed in a hurry.

Almost overnight, silent films and their tinny, tinkly musical accompaniment became a musty anachronism -- relics -- harkening back to the days of buggy whips and hand-cranked Model T Fords. In fact, film audiences were so enamored of the new "talkies" that their silent counterparts languished in film vaults as their notoriously unstable nitrates broke down and they turned into useless, brittle junk. Only a small fraction of the films made in the silent age even survive today; many disintegrated in the cans or went up in flames, while others were recycled to recover the silver nitrate from the film stock. Entire bodies of work have simply been lost to the ages.

Given this, it would seem logical that silent films, let alone silent films accompanied by a live musical score, would have gone the way of T. Rex. Not so fast. Last August, Austin's Alamo Drafthouse Cinema screened a restored print of Fritz Lang's silent classic Metropolis, featuring a score composed and performed by local Kraut-rock combo ST 37, to wildly enthusiastic, sold-out houses. Lang's sci-fi masterpiece about a dystopian society had been mangled and manhandled a few times over the years; different soundtrack treatments having been tried. One of the more recent efforts, a score written by Italian synth prodigy Giorgio Moroder and executed by such Eighties luminaries as Freddie Mercury, Pat Benatar, Loverboy, Billy Squier, and Adam Ant, met with mixed results.

The hypnotic strains of ST 37, on the other hand, proved to be the perfect complement to Metropolis' soulless, dehumanized world -- a place where little happiness or hope exist. Alamo Drafthouse co-owners Tim and Karrie League had tried the concept of silent films and live music before, in the theater they owned in Bakersfield, California.

"We had wanted to do it," explains Karrie League, "because at our other theater, we had done it with The General, where we had somebody come in with a piano and just compose on the spot. That was a lot of fun. Then we started thinking, "Wouldn't it be kind of neat if we had more of a modern score instead of the stereotype tinny piano?'

"We were just throwing that around with some of our employees, and one of our guys who's a drummer came up with the whole Metropolis/ST 37 idea. So, we wound up approaching them through the one employee whose idea it was, and they were all for it."

The long-running local band became Lang devotees for a summer, reading the monocled director's weighty biography and studying the film over and over, while taking copious notes on index cards for the purpose of composing a a scene-by-scene structure on which to build a score around. Eventually the index cards expanded into 40-plus pages of notes.

"Eventually, I condensed 700-some-odd scenes into 40 different moods," explains ST 37's Scott Telles. "I took a bunch of notes, wrote some new things, and cadged a few bits from some stuff we were working on."

Case in point: The band gleefully lifted bass lines from both Motörhead's and Kraftwerk's song versions of "Metropolis," submerging the riffs deeply enough in their own hypnotic drone that no one would notice. Laid over robotic rhythms were washes of synthesizer noise and tape-loop effects to heighten the air of alienation and dismay that pervades the movie. The band's painstaking work paid off, the end result being a different take on Lang's classic -- a runaway success for the band and the theater both, and the beginning of a series of similar projects for the Alamo Drafthouse.

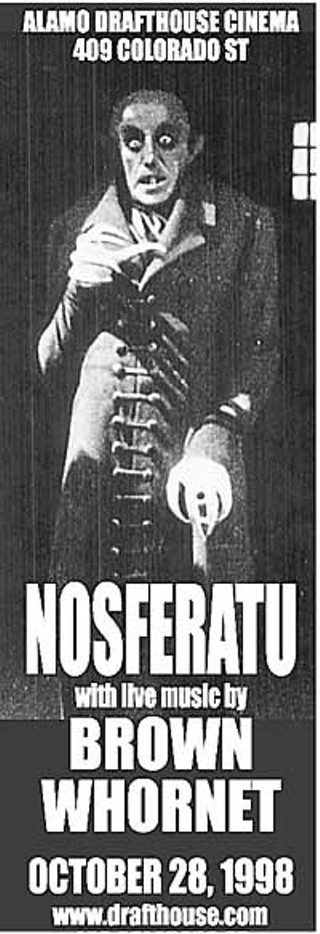

Next up, Austin's Brown Whörnet (see accompanying feature) provided the musical accompaniment for F.W. Murnau's 1922 classic, Nosferatu. The band was posed with the problem of coming up with something fairly quickly, since they had just come back from a tour and only had two weeks to pull together a full musical score.

"Someone loaned us a copy of the movie and we watched it many, many, many times,"says Brown Whörnet's Jimmy Burdine. "The key for us was just to learn the film as much as possible. Then the goal was to enhance it. The music was not necessarily what we would sound like live."

With the band's eight-piece lineup, Burdine says it was somewhat of an undertaking to get everyone pointed in the same direction and come up with a coherent end product.

"It was a little stressful getting ready for it," he recalls, "but once it came down to the final rehearsal with the film playing, we could see it come together."

Brown Whörnet's interweaving lines, alternating between atonal and melodic, elegant and dissonant, proved to be the perfect complement for the eerie, Expressionistic aura that shrouds the first-ever vampire film. Murnau's unforgettable images of the grotesque, ratlike Count skulking through the streets of Bremen were perfectly suited for Brown Whörnet's instrumental skronk. Again, the teaming of silent film classic and live musical accompaniment was a resounding success, enough so to book the event again this October.

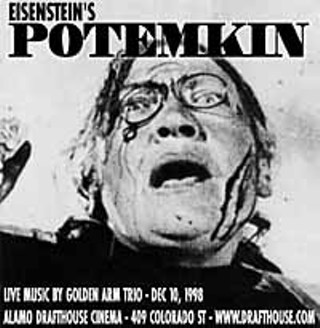

Avant-jazz concern Golden Arm Trio got their chance next, paired with Eisenstein's seminal Battleship Potemkin. The ever-revolving local band's mainstay, Graham Reynolds, notes that he made it a point not to listen to the original soundtrack -- a piano score by Shostakovich; in scrupulously avoiding musical cross-pollination, Reynolds was able to come up with something drastically different and highly original. For the project, the band's ranks expanded to a 10-piece, the compositions leaving less room for improvisation and therefore a more exacting execution. The jazzoid grooves of Golden Arm Trio went somewhat against type for the film, but somehow it worked perfectly. In fact, nothing less would have worked.

Potemkin is so pivotal to film history and so profoundly important that it should be seen by wider audiences than film-school types huddled in campus auditoriums. It set forth ideas on editing, montage, and the subtexts of film language that have been the subject of exhaustive academic work and have influenced every narrative film to come down the pike since then. Reynold's Golden Arm Trio sought to provide an alternative to the original score, rather than try to reinvent it, and pulled it with panache. By doing so, they exposed new, grateful viewers to Eisenstein's remarkable film.

If Golden Arm Trio's treatment of Battleship Potemkin was something akin to a seminar in film history, then local bluesman Guy Forsyth's score for Buster Keaton's classic The General, screened in January, was like a Saturday afternoon matinee: pure, unbridled fun. After viewing the comedic tour de force over and over and over, Forsyth says he saw his challenge as composing a score that supported the film instead of upstaging it.

"I wanted to get as far out of the way of the movie as possible," he explains. "It's a film that would be totally entertaining to watch in complete silence, so everything had to have something to do with the action going on so it wouldn't detract from the film. We had to try to be as invisible as possible. To do that, we had to try to stick closely to elements of style, quoting Civil War-era songs and staying with traditional Americana instrumentation; of course, most of my musical experience is in weird old American music, instruments like the dobro and fingerpicked guitar, harmonica, and whatnot."

Like Brown Whörnet, Forsyth's busy schedule meant he had to pull something together quickly, so he wound up using a song or two from his regular set. More in keeping with the traditions of such films, he and his band wrote themes for various scenarios, such as when the locomotive would appear, love themes, chase themes, etc. It all had to be written, though, keeping the The General's tremendous forward momentum in mind. The group's string-band lineup was augmented with a sample of bass drum sounds, a rain stick, a musical saw, and a variety of percussion instruments. The band's predilection toward l9th- and early 20th-century American music and the vaudeville background of a performer like Buster Keaton resulted in another perfect marriage of sight and sound. In fact, Forsyth and crew can't wait to be teamed up with another film for a repeat performance at the Alamo.

While Forsyth and The General was perhaps the funnest teaming of the series, Kamran Hooshman & the 1001 Nights Orchestra performing alongside Thief of Baghdad was the most exotic. The film's plot involves a princess being courted by three suitors -- a Chinese man, a Persian, and an Indian envoy -- while Douglas Fairbanks plays a swashbuckling con artist who naturally captures the prize. Given the Austin-based orchestra's instrumentation -- zither, hammered dulcimer, Persian drum, sitar, and other indigenous instruments -- 1001 Nights' tightly scripted performance came up with themes that corresponded to the nationality of each suitor, while Fairbanks (of course) had his own heroic theme music. The results were so successful that the 1001 Nights Orchestra has considered taking the show on the road, especially considering the amount of time that was devoted to putting the score together.

Following up Thief of Bagdad, which local audiences gave clamorous standing ovations, The Unknown, a melodrama with the great Lon Chaney as an armless man with an unrequited love for Joan Crawford, was chosen for its odd history.

"A French film collector died and donated his stuff to some sort of governmental film-archive entity in France," explains the Alamo's Tim League. "He had about 500 film cans which were labeled "unknown,' and one of them actually had a print of The Unknown in it! Anything that was incomplete or he wasn't sure what it was, he just labeled "unknown,' and among them was this pristine print. That's when they struck all the prints that are out there now."

The film had literally not been seen by anyone for decades, until the chance discovery. The Alamo brought the film to the screen in June. Since the movie is set in a gypsy circus, the Gypsies seemed a natural choice for the score, with traditional Gypsy arrangements and instrumentation and vocals in Gypsy dialect.

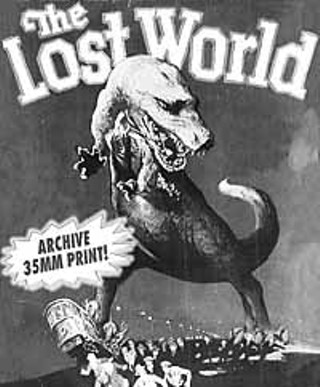

Which brings us to today, September 9, and the Alamo's latest screening, The Lost World, a seminal early sci-fi film from 1925. Taken from a Sir Arthur Conan Doyle novel, The Lost World boils down to a group of explorers laid siege to by a nest of stop-action-animation dinosaurs. After languishing in the dust of film history for decades, the film was rescued in 1991, with private contributors such as Hugh Hefner paying out a sizable sum to restore lost footage that had been discarded in previous edits and bringing the film back to its original length after 72 years. With exacting attention to detail, even the color-tinted segments of the original film have been replaced. Better still, The Lost World has only made the rounds of a few select cities, making its Austin stand a rare event; a second screening has just been added for the following Thursday, September 16. Given the Alamo's previous track record with such screenings, Brown Whörnet and Golden Arm Trio will be putting their heads together and assembling a 25-piece orchestra for the presentation. The results should be interesting.

So, for that matter, should be the Alamo Drafthouse's continuation of this series. Believe it or not, the drafthouse-cinema concept is not unique to Austin; movie theaters with similar formats have sprung up in Atlanta, Chicago, Minneapolis, Orlando, Portland, and a number of other cities. What is unique is the Alamo's marriage of live, contemporary music and 75-year-old silent films. Sometimes we Austinites tend to be a bit self-congratulatory, nearly dislocating our shoulders from vigorously patting ourselves on the back. We do, however, have a vibrant music scene, especially compared to many other cities, and the local community at large has an awareness of the film world that's somewhat above the norm. The Alamo has been able to come up with the perfect nexus of the two arenas, appealing to music fans and movie lovers alike -- not that they're mutually exclusive to begin with.

In fact, the Alamo folks have been nothing if not adept at marketing, inviting such personalities as Rudy Ray Moore, Doris Wishman, and even bustploitation king Russ Meyer to put in appearances during screenings of their films. They've been able to pull off concession tie-ins for some films as well, such as the all-you-can-eat spaghetti platters to go along with Italian Westerns, or the free 40-oz bottle of Schlitz Malt Liquor to accompany blaxploitation films. The theatre's current cannibal film festival, complete with goodies such as beef jerky cooked up specially, should be yummy. With the silent film series, though, the theater has been able to pull off something that has a much deeper importance.

Currently, we live in a time when there are hordes of moviegoers flocking to see the latest Jim Carrey vehicle and who can hardly be made to watch something that's in black and white, let alone silent. Read viewer comments in the Internet Movie Database and you'll find people who dismiss the work of Welles, Wilder, or Wyler as "boring." When people are spoon-fed drivel while never being exposed to anything else, their scope becomes limited and they accept mediocrity as the norm. With their ongoing series, the Alamo Drafthouse has brought new relevance to films that have an important place in movie history. It's proven enough of a success, certainly, to have it continue; future screenings include Peter Pan for the younger set of music fans, Charlie Chaplin's The Gold Rush, Harold Lloyd's Safety Last, and more Buster Keaton movies. Tentatively scheduled for November 18 is a screening of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, with a score by the Friends of Dean Martinez.

Considering the age of silent movies, the rights to many of these films will soon slip into public domain, which will make it much easier to exhibit them; the Alamo ran into problems when they received a cease-and-desist order from the executor of Chaplin's estate when City Lights was up for a screening. The music of popular Austin acts like ST 37, Brown Whörnet, Guy Forsyth, and Golden Arm Trio help expose movies to new audiences that may never take two hours to sit down and experience them otherwise -- audiences who may never have even seen a silent film before -- turning something that would otherwise be considered archaic into a kinetic and fresh experience. ![]()

The Lost World, with live musical accompaniment by Brown Whörnet and Golden Arm Trio, screens twice tonight, Thursday, September 9, at 7pm & 9:30pm; and next Thursday, September 16, at 7pm & 9:45pm