Victory Gardens Redux

A Resurgence of Urban Agriculture

By MM Pack, Fri., Feb. 20, 2009

Eating is an agricultural act.

– Wendell Berry, 1990

Eating is a political act.

– Alice Waters, 2001

Victory Gardens offer a way to enlist Americans, in body as well as mind, in the work of feeding themselves and changing the food system.

– Michael Pollan, 2008

Growing vegetables at home is agricultural, political, practical, and symbolic – a personal, take-charge stance during economically precarious times, when the quality of commercially produced food can be less than desirable, and food "safety" isn't exactly what we believed (think peanuts).

Throw in fresh air and purposeful exercise, add the satisfaction of eating the results, and you have many Americans newly engaged in digging up lawns and planting vegetables. Seed companies report 2008 sales increases up to 40%; the National Gardening Association expects even stronger growth in 2009.

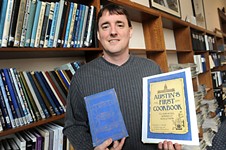

City gardening with political overtones isn't a new idea. Urban agriculture has been around since the 18th century; its popularity waxes and wanes with economic tides. We associate U.S. "victory gardens" with World War II, but the term was coined near the end of World War I as the Allies began winning. Previously, patriotic plots were called war gardens or liberty gardens (and sauerkraut was renamed liberty cabbage). Five million gardens were planted across the country in 1917 to 1918, producing food worth $875 million.

Austin did its part for the Great War. A 1918 Housewives' Bulletin states: "The War Gardens Committee reports ... ninety percent of the men, women, and children of Austin have planted gardens. ... They are not only making the patriotic response to the Allies and our Government's appeal for an increased food supply, but they are robbing the doctors of spring patients, and reducing the high cost of living."

Urban gardening declined between wars, but only 12 days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, a National Defense Gardening Conference revived the victory garden idea. By 1943, Americans planted 20 million gardens and produced 8 million tons of food (40% of all vegetables consumed nationally). In solidarity, Eleanor Roosevelt tended carrots and peas on the White House lawn.

Eleanor's vegetables weren't the first on the White House grounds. Early presidents had to fund their own households; John Adams planted the first garden in 1800. Thomas Jefferson and John Q. Adams added fruit trees; in 1835, Andrew Jackson built an "orangery" for tropical fruit. This was razed in 1857 for vast greenhouses (demolished by Teddy Roosevelt in 1902 to construct the West Wing). Woodrow Wilson grazed sheep on the lawn during World War I, and his wife grew vegetables. And there's been a small vegetable garden on the White House roof since the Clinton administration.

Today, there's a groundswell movement promoting a garden on the White House lawn. Roger Doiron of Kitchen Gardens International has collected 10,000 signatures for his petition (www.eattheview.org), and the White House Organic Farm initiative (www.thewhofarm.org) has gathered 10,000 more. In the New York Times, Michael Pollan called for "a new Victory Garden movement" seeking victory over "high food prices, poor diets, and a sedentary population. ... How America's first household organizes its eating will set the national tone ... communicating a simple set of values that can guide Americans toward sun-based foods and away from eating oil."