What Would Jean-Luc Do?

In a post-digital world, is cinema dead or just rebooting?

By Marc Savlov, Fri., July 24, 2009

"End of film/End of cinema" – closing titles of Godard's Weekend (1967)

It's not exactly Paris, May 1968, but a Godardian sort of revolution is very much in the cinematic and cultural zeitgeist, both here in Austin and virtually everywhere else. The enfant terrible of the French New Wave is, at 78, no longer a cultural force to be reckoned with (outside of the rarefied hall of film theorists and film buffs, anyway), but the director's blurring of the lines between the personal, the social, the political, and the filmed has never been more relevant. Today, now, here, everywhere, everything really is cinema, in the sense that everything is filmed, recorded, taped, streamed, whether with clear narrative, artistic, or communicative intent – as evidenced by the YouTube, Twitter, Flip MinoHD, pro-sumer, personal filmmaking "revolution" – or by passive devices: barely glimpsed traffic and security cams, closed-circuit television, Google Earth, and all the myriad lenses of the unknown digital observers. Alphaville? Not exactly, nor is it as Orwellian as it appears at first glance. (Although in this brave net world, it helps to think like Godard: Nothing is as it appears at first glance.)

How much content is out there? There is no exact figure available because it's changing by the microsecond, but the news and numbers aggregation site comScore ("The next generation of global digital audience measurement") issued a press release on June 4 titled "Americans Viewed a Record 16.8 Billion Videos Online in April Driven Largely by Surge in Viewership at YouTube." None of those homemade uploaded videos were, say, Pierrot le Fou, of course, but still. The groundswell of the digital filmmaking revolution has turned into a veritable tsunami, heedless of borders, governments, ideologies, and aesthetics. Think of Tehran without Twitter, of Burma without its VJs. The genies of the digital now have exited their proverbial lamps, and the control systems of the analog then are crumbling. Art always happens, as does dross, but suddenly, seemingly overnight, the potentiality for it is in the hands of billions instead of just those with the cash flow and wherewithal to acquire the pricey 1080i production means. Now art is free, or as free as information wants to be.

What does it mean, then, to be a filmmaker when the core tools of the filmmaking process – cameras, editing programs, online distribution networks (or lack thereof) – continue to rise atop a democratizing wave of the ever-more affordable and more available? If anyone can make a film, narrative or otherwise, what does that imply for the art form as a whole? What does it do to the artist? And what does the future hold in store in a world where everything from moviemaking to gaming to journalism to the very concept of personal online identity (or, really, identities) is splintering into a million niche-y fragments in less time than it took for most rural American populations to get the telephone?

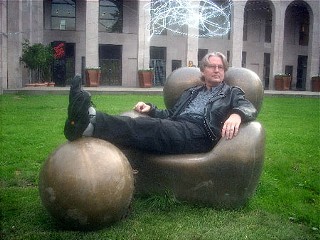

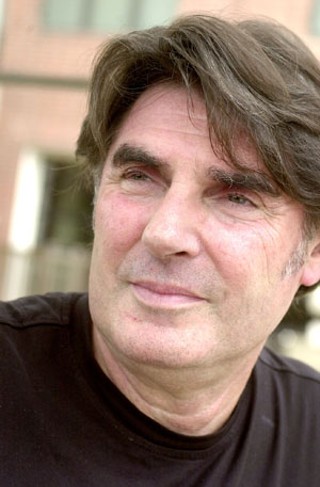

To try and get a handle on how the digital revolution is changing both filmmakers and the world they film, we posed the same questions to four film- and future-related personages. We spoke by phone with filmmaker Richard Linklater and Janet Pierson, producer of the South by Southwest Film Festival; chatted via e-mail with Bruce Sterling, author, futurist, and international design raconteur; and sat down in person with Derek Woodgate, author, revelator, and president of Futures Lab (www.futures-lab.com), then edited the four interviews together for a freewheeling look at the revolution-in-progress.

The end of cinema? Not even close. The beginning of a new nouvelle vague? Well, just maybe.

Austin Chronicle: Digital video is the new film, and even Jean-Luc "The cinema is truth 24 frames per second" Godard is no stranger to it (see In Praise of Love). It's cheaper, it's easier, and by now it's more or less omnipresent and creating seismic shifts across the board, from Iran's Twitter/YouTube moment to the HD flat-screen monitor dominating the collective media room. It's not so much a case of "cinema is everything" as it is "cinema is everywhere," right?

Bruce Sterling: We got to see some exciting handheld clips from the Iranian election, but that doesn't mean all supposedly stolen elections get some popular, universal documentation. It's probably easier to rig and steal elections now than it has ever been. Regimes all over the place do it routinely; skullduggery flourishes, it's not exposed, or if it is, the act of exposing it is of no significance; it gets no audience and no political traction.

Even the stuff that really and truly is video'd all the freakin' time, like downtown London, is not within an archive where it can be smoothly and uniformly assembled and searched. The cops own that stuff. You don't get to ramble through that any more than you get to ramble through the cops' various other databanks. It's not a 1984 situation of universal surveillance, either, because even the cops forget about their own video; they're not aware that it's on, and they forget about its functionality. ...

What happens when you get "seismic shifts"? You don't get universalized visual access to everything; in seismic shifts you get huge cracks, broken foundations, shantytowns, missing stuff, crevasses where things fell into holes. That's what we have. We have a volcanic, seismic landscape, and the closer we get to the digital center of that volcano, the faster stuff burns up.

Richard Linklater: You've got to think that when the Iranian uprising was happening, [pioneering Soviet documentarian] Dziga Vertov was smiling somewhere. That was the full manifestation of what these filmmakers have been striving for over time. Not necessarily Godard; I'm not sure how democratic his intentions were, but there's always been this idea that if everyone had a movie camera, then all this great stuff would happen. Like everything else from any other revolutionary period, it's wildly idealistic, but that doesn't make everyone an artist. You can now just point and capture things, and that's a great thing, obviously, for the world and communication, but it doesn't necessarily equal art.

[Would] Tienanmen Square have been different had there been [Twitter, YouTube, and social media] there? Would the tanks have rolled in? Probably not. I think that's the one thing that kept the Iranian government somewhat in check: Their realization that, you know, "Oh, shit, we're going to look bad." So this is a nice check and balance on oppressive states and situations.

AC: Have the basic tenets of what it means to be a filmmaker changed with the move from actual film to digital media to HD and beyond?

Janet Pierson: What's changed is that the traditional system for distributing and exhibiting films is no longer what it was. And it's not finished changing yet, so people still don't know what the new system is going to be. You have people who are immersing themselves visually in different media for different lengths for different ends, and it exists, but what it actually stands for or means is, at least for now, unknown. I was reading a review of [former Wired magazine Editor] Chris Anderson's new book, [Free:] The Future of a Radical Price, in The New York Times and they talked about the culture of amateurism taking over. That's the only outstanding part of the change that I can see. The culture of the amateur says, "I can do this," and I love the DIY culture attitude as a whole. I'm a big fan of Maker Faire. I love that stuff because it's like, 'Hey, make something; be creative.' Why not, you know? Why isn't that a healthy thing? The question is, how does that get supported, and how do you weed through the mess and the clutter? That's what's really hard.

I worry about the fact that I'm getting my news from Twitter and Facebook from people I already know, so I'm not hearing things that I'm surprised by or being pushed outside my boundaries. In a way, the world has become extremely insular from a technological and communicative standpoint. Several people at South by Southwest this year told me that it was the best festival ever and the films were great, but they ended up at a lot of their friends' screenings instead of seeing all the other wonderful stuff that was not directly related to them or their friends. What it boils down to, I think, is a matter of time. There's so much! How do you weed through all of the screenings and films and events to get the most out of your festivalgoing experience?

Derek Woodgate: A lot of what's going on now with film, or what film is morphing into, has to do with social change, the interaction between the film and the audience and our ability to deal with those changes and interactions. I think the most important is our ability to deal with nonlinear storytelling. I don't think that most people outside of the gaming community are able to deal with that yet, but it's definitely an emerging space in the world of film. Examples of what I'm talking about would be Memento, Timecode, or Requiem for a Dream. One of my favorites was Synecdoche, New York. I think that's a big coming thing, the ability to deal with nonlinear narrative. It's not so much the filmmaking that's changing as it is the viewers, and a huge amount of that change is coming about directly because of gaming and gamers.

There's also the fact that we can all make films now at home or on our laptops or wherever. Final Cut Pro is standard equipment in the teenage bedroom these days. Five years ago, it was virtually unknown. It was a professional tool, now it's a household tool, and one that's fairly easy to use and intuit. Young people are picking this up as they go along without any formal training, and I think that's also a critical element in the digital revolution: self-education.

AC: So in terms of filmmaking – of consciously attempting to create a narrative or documentary film – if everyone with the will to make a movie can now afford to do so, what effect does that have on the concept of being a "filmmaker" and on "cinema"?

Linklater: It's no different from the fact that everyone can be a novelist. Everyone can be a painter. Everyone can be a sculptor. What's great about this is that it doesn't give anyone an excuse. When I was first starting out, it used to be you could just sit around in a coffee shop and talk about all the great films you would make if they would only let you. You don't have that excuse anymore. It's like someone jawing on about all the great novels they want to write. Well, you know, write 'em! If that's who you are, you would be writing instead of talking.

There's a skill involved, and one of the first things people find out in filmmaking is that the skill isn't being able to push a red button on a camera. The real skill is in storytelling. It's a timeless kind of thing. If you really want to make a narrative, that is. I'm not talking about documentary filmmaking, which is the overwhelming amount of the images and what's being done with all this new technology. They're two different things, and I don't think one is better than the other. I'm just saying, without sounding too elitist, that there's a more rarefied skill in storytelling via images, actors, narrative, and all that.

Sterling: There was "cinema" when the act of filming something was a deliberate artistic act, when it required intentionality and the focused use of expensive equipment. When those intentions and limitations go away, we don't get "filmed everything." We get today's different landscape of other intentions and limitations. They have to do with phenomena like storage, archivability, searchability, the willingness of an audience to pay attention and act on the data presented to them, new commercial constraints, intellectual property, collapsing business models, state security.

And, especially, the rapid decay of digital media formats.

Megatons of the "everything" is just plain decaying, vanishing, like the Polaroid snapshot. "Wow, with this Polaroid, I can get an instant picture of everything and anything!" Yeah, sure, pal, sort of: You were there, and you documented it, and it was instant and without much in the way of focused intention on your part, but how long does that unstable image last, and how long does that unstable production system last, and how do you get anybody to sit still and appreciate a freakin' Polaroid? It's a Polaroid; it didn't make you into Ansel Adams. The Polaroid didn't make everything into art-photography. The Polaroid can't handle heavy-duty critical assessment, and neither can a YouTube cat video that takes less time to make and upload than it does to think about.

AC: Assuming that the filmic playing field is semileveled and everyone, including the hooligans, are out on the pitch, is there going to be a point when there are just too many people creating films/content for festivals like South by Southwest to process? Has that already happened?

Linklater: When I first went to Sundance in 1991, I think there were something like 250 films submitted. I thought that was just a staggering figure at that time, knowing what I knew about how much time and money and effort it took to make a feature film. Two hundred fifty indie films made in the U.S.? I'm envisioning personal bankruptcies; I'm envisioning families falling apart; there's only 16 slots, and of those not even that many get distribution deals.

And now it's some insane amount of [Sundance] submissions, like 6- to 7,000? It's crazy. It's good, but it's crazy. Looking back, there were so many bad films that got credit just because you finished them. It was like: "Wow, you made a film? Hell, we'll all watch it." It was such an accomplishment. Now it's like: "You made a film? So what?" And I think that's good because it makes people concentrate more on the content and the quality of the content and the work itself, as opposed to just the fact that you finished something.

It's an interesting time. I think it is the articulation of a dream. But it hasn't quite ushered in this golden age of little personal films and Truffaut's idea of personal cinema. It's created a glut for the Janet Piersons of the world who have to go through so many films.

Pierson: [From the standpoint of a South by Southwest Film programmer,] it's a problem. John [Pierson] is fond of talking about the impossibility of [seeing all the films opening on a given weekend in] New York City, so then how is it at all possible for anybody, even people like us who try to keep up, to see everything that's coming?

I'm a lot more optimistic than some other people because I see it all as a Darwinian process. Everybody can go ahead and try to make a film, but they're not all going to get seen, they're not all going to get appreciated, and I'm going to do what I can to try and filter through and find the ones that are exciting. And there are people all over the world whose whole m.o. is to try and find work that's exciting, so that's happening all the time.

There's lots of films that don't get homes. One could look at that and say, "What a waste," but on the other hand, people want to be creative, and how can you say no to that?

AC: Are microcinemas and streaming minifests the solution, then? And ultimately, how does the medium of cinema – narrative, nonlinear, neo-Godardian, whatever – survive and thrive within and beyond this period of incessant technological flux?

Linklater: How to get things seen and how to work it out so that all these films that are being made can be seen by audiences [is the next revolution]. And that hasn't happened yet. Nobody's quite hit on any one functioning solution. There's niche distribution, online and so forth, but the real revolution has yet to occur. And that's where I tell young filmmakers to focus on. I think the next few years are going to be really interesting in that regard.

Pierson: I guess the most important element to bear in mind when it comes to discussing the state of filmmaking today is that just because there's more doesn't mean there's better. And there's still a magic that some people have in terms of how they organize anything – words, images – that they give it a special kind of ahh!, you know? It's that a-ha! moment that makes you think, "Wow! How was that put together in such a way that's fresh and exciting and is something that I haven't seen before?" And that's really, really hard to do, but a couple of people will always be able to do it regardless of how many people try.

Sterling: The media landscape we see today is a huge Gothic thing of rags and tatters and empty crypts and abandoned battlements and formerly august halls of public debate where today you can hear crickets chirping. And outside, and in the drained moat and on the stairs and in attics are huge brawling flea markets where people are rioting and burning tires and punching each other and just blatantly stealing music, books, video, cinema. ...

They're stapling and nailing and pasting mashed-up ruinations of stuff, like a Godard movie that's turned into a 27-second grainy particle of Godard the size of a YouTube postcard. And yes, you can get that scrappy mess anywhere on the planet for nothing – if you know where to find it. We don't get a billion Godards. We may very well get zero Godards. Or we get about as many Godards as we now have epic poets.