Gung Ho

Patti Smith

By Jody Denberg, Fri., March 31, 2000

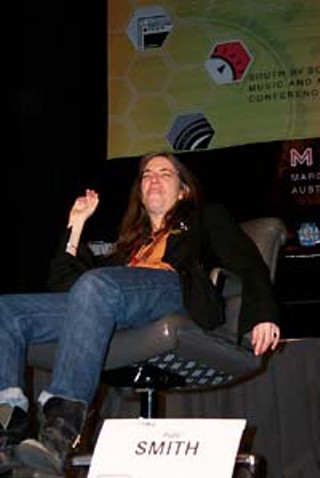

Last March, after South by Southwest, the Chronicle printed an interview that 107.1 KGSR Program Director Jody Denberg had done with music festival headliner Tom Waits, who the longtime local deejay, writer, and music scenester had helped lure to the conference in the course of their conversations for a promotional interview disc released in conjunction with the singer's then-new album, Mule Variations. Lo and beholden, this year, while producing a similar interview disc, Denberg once again managed to entice a music-industry legend to Austin for SXSW -- this time, the one and only Patti Smith. Having run a short excerpt of their interview in one of the three Daily Chronicles produced for the conference, we thought post-SXSW a good time to share with our readers the full, unexpurgated, Gung Ho interview.

Austin Chronicle: I wanted to wish you a belated Happy New Year, Happy New Decade, Happy New Century -- Happy Birthday! I wasn't sure if those traditional ways of looking at time mattered to you.

Patti Smith: I enjoy a revolutionary point of view that breaks tradition apart, but I also do love tradition. I love history and I saluted the new century joyfully. So I'll go along with it.

AC: The last major work you did was in 1998, a compilation of your poetry and lyrics called Complete. Now that you have a new album out -- Gung Ho -- Complete isn't complete anymore.

PS: Well, it's [laughs] -- yeah, it's incomplete. I'll have to do one called Completed. We did update the paperback with as much of Gung Ho as I had ready at the time. And what we will do is, on the new album, include all of the lyrics for those who want them. So I did the best I could to get them in under the wire for the paperback.

AC: The album title Gung Ho has so many implications. What were you trying to communicate with the title?

PS: Well, it's got two things. One, it's a play on words, because the title cut "Gung Ho" is an overview of the life of Ho Chi Minh, looking at what drove him as a patriot and a person who foresaw and worked all his life on creating an independent Vietnam. He was a very special man, but he was also a very common man. And I thought of him sort of like Gunga Din, who had those qualities. So it has that "gung-ho" sort of play on words.

But also, when I was a kid, my father fought in World War II, and my mother always used to use that term, gung-ho. It was used for someone who was putting their whole heart [into something] and really believing in what they were doing and even going into a difficult task with positive, idealistic energy. I decided that I wanted to enter the new century like that. We have so many things that are wrong, so many difficult things. I wanted to go into the new century in a positive, work-oriented frame of mind.

AC: There's also the fact that "gung-ho" is a Chinese expression, and you've been outspoken in trying to preserve Tibet's cultural heritage and return the Tibetans from exile. When did your interest in Tibet begin?

PS: When I was about 12. I think I must have seen the movie about Shangri-La when I was a child. Ancient civilizations and ancient religions and Buddhism have always interested me, so I started doing a report when I was 12. I was in school and the teacher said, "Everyone choose a country. You must spend a year doing a report." I chose Tibet. She said, "You can't choose Tibet. Nothing ever happens there. You have to have current events. You have to cut out articles in the newspaper. No one knows about Tibet." I said, "I want Tibet." It was January of 1959. Kids were laughing at me and teasing me, but I stood my ground and just couldn't find hardly a thing. I used to pray, "Oh, will something please happen in Tibet so I could write my report."

Well, in March '59, they were invaded by the Chinese, and the Dalai Lama, who I had gotten very attached to in my studies, was feared killed. It was not exactly the news that I was praying for, but I became very aware of their situation. What really struck me was my father, who had fought in World War II. He explained that he had fought in it to set an example and help the world be free. I couldn't understand how my father had done all of this work, and I thought all the wars were over. I couldn't understand why a country's freedom was being taken away and nobody seemed to care. So it's been on my mind for a long time.

[Still], never in my life, as a skinny 12yearold with a passion for Davy Crockett, did I ever think one day I would be doing even some small help for the Tibetan people, but I had the opportunity to meet and talk with His Holiness. It just shows, you know, life -- it's unbelievable, life. If you stick around long enough, the most wonderful things will happen to you.

AC: Calls for activism and awareness in your music are nothing new, and on the new album, you continue that tradition. Do you feel it's your calling as an artist to try and inspire righteous change?

PS: Well, I'm not a politician. I'm not articulate, politically. But I do find that I seem to have a calling to at least speak out. I'm an American citizen and that's part of the responsibility, I think, of being an American. We're free. We have freedom of choice, and we have a responsibility to that.

And also, I look around at other people and the work that they do. For instance [Gung Ho's opening cut], "One Voice" was inspired by the work that Mother Teresa did. I look at this little woman, you know, this one small woman and the tremendous impact she had on thousands and thousands of people. Not only with her hands-on work, but the way she inspired others to perform simple acts of charity throughout the globe that will mean so much to a person. Great or small, the idea is that they're all appreciated.

AC: "Glitter in Their Eyes," from Gung Ho, comes across as kind of a rage against the rampant consumerism that's going on right now.

PS: Well, actually I co-wrote "Glitter in Their Eyes" with Oliver Ray. It was Oliver's concept, based on things we talk about all the time, and it's pretty much exactly what you said. The concept of the song -- it's actually addressed to young people -- is, "Look out kids, the gleam, the gleam." It's sending out both a warning and a caring salute to young people, who are constantly being exploited by business. They're targets. Children aren't children anymore, they're a demographic. They're a consumer demographic. And like you said, it's rampant consumerism. Not just on the part of the consumer, but on the part of people who see people as potential consumers.

AC: Along with external-looking songs on Gung Ho, there are also songs that look within. I was wondering if the new "Lo and Beholden" was your own current romantic situation set behind some poetic veil?

PS: Well, it's not -- not really. This is a real classic Patti Smith/Lenny Kaye song, because the music is so much like Lenny. It's taken from the point of view of Salome, who has been exploited by both her father-in-law, King Herod, and her mother; King Herod because he's after a piece of her youth and beauty, and her mother, because she wants the head of John the Baptist. So this beautiful girl has forever been tainted. She's known as one of the villainesses in the Bible, because she was always a simple, beautiful girl, asked to dance and used by her mother to get the head of John the Baptist.

That's what it applies to directly. Indirectly, [it's about] how we're also exploiting youth and beauty these days. Girls are being exploited terribly. And people are being exploited because of their desire for celebrity and things like that. They're being exploited by these talk shows like Jerry Springer and stuff. They'll reveal anything about themselves or make up things about themselves to seem important.

AC: There's a beautiful harp on "Lo and Beholden." For the last 25 years, you've played mostly with the same core group of musicians. Is it simply a matter of loyalty for you or is the idea of being in a long-term rock & roll band part of what gets you off?

PS: I never came into recording as a musician or anyone with any training or even any desire to do records. I really came into recording as a performer who was concerned about the state of rock & roll. My only concept of performing was that people had a real group, like the Rolling Stones. I thought, when you have your group, that's your group.

The only reason I've made changes in my group at all was if a person was ill -- had to leave for a while. In the Patti Smith Group, we had our core group. To me, that was a rock & roll band. That's what I had, a rock & roll band. There was no pretenses of us doing anything else. I was completely untrained and just going on instinct and also sort of an idealistic idea of what a rock & roll band was, which includes the loyalty, the camaraderie, and you know, the struggle. That meant more to me than trying to make things technically perfect or having the optimum guitar player or something. I just liked the people that I worked with. We all believed in the same things.

Lenny Kaye and Richard Sohl and I started together. Richard Sohl was a very gifted piano player. He was classically trained, just a wonderful person to work with and improvise with, who I thought I'd work with my whole life. But he died of congenital heart failure in '91. Which was really difficult for me. Jay Dee Daugherty is the only drummer I've ever had. Lenny Kaye has always been my most avid supporter and continues to help in all different aspects of the work. He brought in Tony Shanahan when I did Gone Again. He's a very gifted musician and has some of the musical temperament that Richard had, even though he's a bass player. And [guitarist] Oliver Ray, who has ... who has a real revolutionary spirit, and also brings youth into the group.

We started struggling together on Gone Again, and believe me, it was a struggle because we were at all different levels of experience. I hadn't played for like 15 years. But we have struggled in the past few years and this is our third album together. I really feel like now we're a true rock & roll band, and that's really all I want -- just a true rock & roll band.

AC: Except for a couple of songs, most of the material on Gung Ho was co-written with one other band member. I was curious how you decided which of your band members you were going to bring a lyric to for collaboration on?

PS: I rarely write lyrics first. I improvise in the practice room. Lenny brought the music to "Lo and Beholden," and the band played it. I just improvised, and the song -- how the song felt -- is what I gleaned from it. "Gung Ho," [the nearly 12-minute title track that closes the album], was written because I was studying Ho Chi Minh. I had read several books about him -- read, read all of his works. I walked in the practice room and they were riffing, you know, the band had this riff and I listened to it and I loved it. It just drew me to the microphone. And I started improvising what became "Gung Ho." That's pretty much how I work.

AC: Parts of Gung Ho are a little more fleshed-out and full than the approach of 1996's Gone Again or Peace and Noise from 1997. Was that a result of working with Gil Norton, who had produced the Pixies, among others, and how did you choose him?

PS: Well, I think it's two things. First of all, Gil Norton and his engineer, Danton Supple, are great. They're really great to work with. They're highly respectful. They allowed for us to be who we were, but give us, you know, their expertise and ideas about sound. But they never were invasive. They just enhanced everything that we did. Working with them was a really great experience. It was tough, but really great.

I think the other thing, why this record sounds better and seems even more fully realized, is that now we, as a band, have spent four years together. Gone Again was made just as best we could; Fred ["Sonic" Smith, Patti's husband and guitarist for the MC5] had just passed away, and I was greatly dispirited -- I didn't really have a band and it was hard for me to even want to record. [Gone Again] was really an act of a lot of people coming together, keeping my spirits up. Lenny, Tom Verlaine came in on it. All of the same band members.

And Peace and Noise, I was still getting my feet back on the ground and relearning how to record and perform myself, as everyone else was learning. We were learning to play together and getting to know each other as people. Now, we've been through all kinds of things together and I think this album reflects the trust and the strength that we've built with a lot of struggle. I think it reflects that. But much, much credit to our producer and engineer.

AC: Before Fred died in 1994, he was giving you guitar lessons, even though you'd been using a guitar onstage since the early days. Now I see you wrote two songs on Gung Ho solo. I'm thinking you're still keepin' up with the six-string.

PS: In the Seventies, I got very involved in the sonic aspects of the electric guitar. I worked really hard. I wasn't interested in chords. I didn't bother learning chords in the Seventies. I was totally interested in feedback, sound. Fred actually helped me with that. He helped me wire a Fender Twin [amplifier] in a special way, 'cause he was the king of feedback. That was my essential interest in electric guitar, the sound.

In '94, I really had the desire to write my own little songs, because these Appalachian-style songs were coming into my head. And Fred promised me he would show me chords if I practiced hard. I had an old Gibson from the Thirties, an acoustic guitar, which I still have. He showed me every chord, except we ended and I never got a B chord. But I know all the other chords. That was the last thing that Fred taught me, rhythm, getting a good rhythm, and my chords. Since then, I've actually written several songs. I always think about that, you know, it was like the last gift he gave me. And I've used it well.

AC: Keeping up with your clarinet playing?

PS: Oh yeah. I play a lot of clarinet, and within the band structure, I play a lot of clarinet. I'm actually really proud of my clarinet playing. Fred also introduced me to clarinet, of course. Bought me my mouthpiece and gave me my first clarinet lessons.

AC: You've explored so many avenues of expression over the years, besides poetry and music, beginning in the early days with theater and photography, drawing, painting. I also heard you were working on a novel at one point. Does alternating media keep you fresh?

PS: In some ways it's very difficult, because I have a restless nature going from one to another and it makes it harder to finish things. I'm very lucky to be able to express myself in a lot of different genres, but it's also hard. It's a mixed blessing. The one great thing about it, I've found, is that if you work hard on one skill, it will often permeate the other. You know, I find that if I'm working on the clarinet quite a bit, it helps my singing, it helps my breathing. It takes a lot of discipline for me to finish all of these lyrics and go through the whole process of making an album. But it proves to me, again, that I can finish something. So then, when I go to a book project, when I get dejected or I get, you know, bored or demoralized, I can access the fact that I can finish things if I stick to it.

AC: It seems the artistic vibe also permeates your household and in your family. The last album's title Peace and Noise was conceived by your daughter Jessie. I think I read that she plays some piano, as well. On Gung Ho's "Persuasion," your son Jackson plays guitar.

PS: Well, first of all, Jessie's 12. She's a 12-year-old girl, and she's exploring many things. She writes. She's really looking at the whole world right now. She's curious about the whole world.

Jackson is 17. He really picked up guitar after his father passed away. He was about 12 years old. And Jackson actually has a lot of his father's gifts. He didn't know that he had them. He didn't show any real interest in music until after his father passed away. He really wanted to be an ice-cream man for a long time. But he has his father's gifts. And he spends a lot of time, you know, studying different guitar players and different styles of music. Everything from Renaissance music to Danny Gatton. He's very involved in the playing of the music and learning. He's not interested in the music business or anything like that.

I really think that the things Jackson and Jessie do or find will be by their own volition. They were well brought up, and there were a lot of different types of things open to them musically and artistically. I think both of them will make their own decisions. As their surviving parent, I can only influence them so much. I really am more interested in being an influence in how they take care of themselves and how they treat other people. In terms of their work, they'll make their own decisions.

AC: Not only does "Persuasion" feature your son on the guitar solo, it's credited Smith/Smith. Did Jackson co-write that or is that a song that, you wrote with Fred a while back?

PS: Fred and I wrote that song for Dream of Life originally. We were addressing album length and we had too many songs, so we never actually recorded it. For this particular album, because it was the last recording that I was going to do in the 20th century, I wanted Fred represented one more time. And I always thought it was a really great song. We put it together as a band; Oliver one day said, "You know, it's Fred's song. We should have Jackson play the solo on it." And Lenny Kaye, who would have normally played it, was delighted to step aside and have Jackson play the solo, and he did a great job. Just came in and did it.

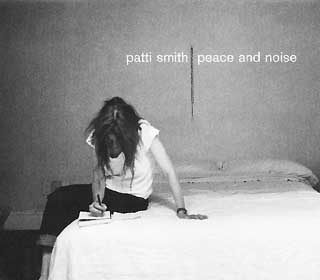

AC: The vision I have of you during the writing process is a spartan one. I think it's brought about by the cover of your last album, Peace and Noise, because there's that blackandwhite picture of you, pen in hand, writing on paper that's resting on a book on the bed. The room is totally unadorned, except for a rosary hanging on the wall. Is my vision accurate or am I forgetting about your typewriter? Have you moved on to a computer?

PS: I do most of my writing by hand. I'm not computer friendly, yet. I do have a couple of acoustic typewriters -- a couple of really old typewriters. Mostly, I write by hand.

In that shot, I was writing. Oliver Ray took that shot, and I didn't even realize he was taking the picture. I was deep in my writing. Mostly I write in notebooks. When I'm writing for the band, like I said, a lot of it starts out improvised, and then I go off with myself and start struggling with the connective tissue of the song -- right up to the last minute. I'm sort of a nightmare for everyone, because at the last moment, I'm still writing lyrics or improvising in the studio. I almost never have lyrics finished. It's just every once in a while. There's just a handful of songs that I actually have had finished lyrics for. It's always right to the wire.

AC: Whether it's lyrics or poetry, what motivates you to write? Is it the process? Is it the end result? Is it the immortality of the work?

PS: It's always different. I mean, I've always written, as long as I can remember. I fell in love with books; it was like love at first sight. I've loved books since I was a small child. As soon as I learned that one could write a book, that one could write their own book, I became interested in writing. I read Little Women and there was Jo the writer, and it occurred to me, yes, I can do that. I've been writing all my life and I write for various reasons: In reaction to things, out of sorrow, out of joy, or out of duty. I record my dreams. I have many reasons why I write.

AC: Is there anything specifically you feel the closest to or that you feel represents you the best?

PS: Well, I really feel this particular album represents me well, because I think I'm at the top of my game in lyric writing. There's always a song or two where I feel like I failed lyrically, because I wasn't ready or the words didn't come. I feel extremely proud of this particular work. Like probably all artists, I can get pretty hard on myself, but I've allowed myself to be happy about this album.

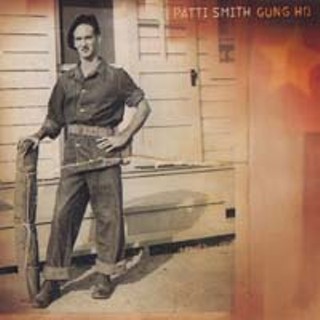

AC: Gung Ho features a picture of your father on the cover. Your sister Kimberly makes an appearance on the new as well. Your late brother Todd was the head of your road crew. Your mom has been known to correspond with your fans. I could be wrong here, but I get the feeling that "China Bird" from the new album has a family connection.

PS: Yes, there is. My father actually passed away in late August, and I was very close to my father. Oliver wrote the music to "China Bird" several months before my father passed away. I heard the music -- he was playing acoustic guitar, and it was the most beautiful music. I said, "I have to have that music. Please let me write some lyrics to that." And I had been struggling with it, because sometimes music is so beautiful it seems like there are no words for it.

I went home to see my father, and my father had a china bird collection. It was a little shelf, and he sent his check every month and they would send him a new porcelain bird. My father loved birds and fed birds all the time. And I looked at the china bird collection and I was just moved to, to write -- something. I was moved by my father's little bird collection and I thought of my father, because it's the style of song he likes. His way of unconditional, abstract love is part of the theme in that song. It's also a love song.

I thought of my daughter, as well. Often two or three people will be within a song. That song incorporates a few people that I love in one little song. We decided to put my father on the cover, because I had this great shot of my father in Australia during World War II, because he served in the Philippines and New Guinea. Just a great shot of him in his late 20s, you know, idealistic, ready, "gung-ho" as my mother would say, with his black beret on.

And the beautiful thing is, because he's so young, I could see my brother. He so resembles my brother. It's like having both my brother and father on the album cover. Both of them were highly supportive of what I do. So I thought it was a nice positive salute.

AC: There was a period of almost 17 years, between 1979 and 1996, when you only released one album, and that was Dream of Life in 1988. One of the reasons you've cited is that you were raising your family at the time.

PS: It's always humorous to me when people say to me, "Well, you didn't work in the Eighties." You know, I worked harder in the Eighties than I ever did in my life. Not only tending to children and washing diapers and all of the different tasks that one performs in raising a family, but I spent hours and hours developing my craft as a writer, studying so that I would have new points of view, new things to say, a better understanding of humankind.

I mean, I even studied sports. I didn't know anything about sports. I learned everything about sports. I watched many Masters tournaments. I knew everything about golf. I learned about basketball. I went through all the [Detroit] Pistons' wins. You know, I did all kinds of things. I learned about subjects that I wouldn't normally be interested in for the sake of comprehending what our society likes and what they do and who they are. I also studied various aspects of art history, religions, the Bible.

So I spent the Eighties, as you said, replenishing myself as an artist and also evolving as a human being, because there is nothing that will stunt one's growth more than staying too long in just being a rock & roll star. It was time for me to evolve as a human being, so I did a lot of work on myself and on my skills in the Eighties.

AC: Gung Ho is your third album in four years. How do you account for your current prolificness?

PS: One thing is my children have gotten to a point where they're old enough that they don't need as much tending to, so I have a lot more time. I've always been a prolific person, but privately prolific. I do a lot of work that no one sees. But I think the real reason is because I've had a lot of input and energy from other people.

Doing albums, for me, has always been a collaborative effort. Even though I enjoy being respected -- having my name respected -- my body of work as a person who does records has been, basically been, collaborative. Right now, I'm working with a very energetic situation.

I had a very difficult period before I began Gone Again. My children were young, my husband was ill. We were struggling, in various ways. Not only with difficulties such as that, but you know, financially. I had a lot of responsibilities. I've had a lot of support from '95 on -- from friends and colleagues and people I didn't even know. People like Michael Stipe. And it's just been, you know, a really good period. I mean, even somebody like Bob Dylan, who I was greatly influenced by and admired from afar, invited me to open his tour in late '95 or '96, I can't remember. I sang with him and he also gave me words of encouragement. So many people have put so much belief in me to help me get back on my feet. I could do nothing but produce work to earn all of their support, all of their energy, and all of the belief that's been put in me.

AC: Now that Jackson and Jessie are older, do you think you might tour more than you have over the past few years?

PS: Probably. Not like Metallica or somebody [laughs]. I can't do that, nor do I have the desire to do that. The way that we perform, every night is different. We really collaborate with the people and the energy of the night. I improvise a lot and it's physically taxing work. We'll probably tour more than on the last two albums.

AC: The last time you visited Austin [before SXSW] was in 1979 on the Wave tour. I'm hoping that if you do some shows in the near future, you'll come our way.

PS: Well, I have to tell you that I have a very cool booking agent. His name's Frank Riley. I said, "I want to go" and then told him the places that we often go that I like. I said, "But the place I really want is Austin, Texas. Can you get me to Austin, Texas?" And he said, "That's a great town." And I said, "I really want to go back to Austin, Texas." And I have three concrete reasons. One is because the people were great. I have the greatest memories of Austin, Texas, because in the Seventies, they had a revolutionary and -- I felt -- responsible and caring radio station. You gave me the name of it earlier.

AC: Right, it was KLBJ.

PS: KLBJ. And didn't Lady Bird Johnson, that was her station? The [deejays], they were given a lot of freedom. Those people still cared about radio as a communication and cultural base, and that was fast fading at the end of the Seventies, so I really felt that Austin, Texas, was holding onto, you know -- you know, keeping the torch burning. Also, I have my happiest American hotel memory staying in the LBJ suite at the Driskill, which it was just really great. I just felt like I was on the top of the world then. So I have really, really happy memories of Austin. I hope that the people will want us to return so that I can get a job there.

AC: Locals always used to tell me, "Ask Patti if the white dress she wears on the Wave cover was bought in Austin."

PS: Yes, my brother Todd bought it for me. I always liked white dresses. I mentioned that I wanted to wear one on my next album, if I could find one, and my brother found one. You know, it was an old-fashioned look, like a sort of prairie girl dress. It was a really thin white cotton. I still have it. It's folded up in a little chest and I still have it.

AC: Yours has always been a concerted effort to make the issue of gender meaningless in rock & roll. Then Lilith Fair came along and made it an issue again. Did you feel like that was a step backward in some ways?

PS: That's not mine to judge. I'm sure they did a lot of positive things for women performers who find it important to be known as a woman performer. That's an important thing to people. For me, I mean, I'm an artist. I feel like I don't want to be genderized as an artist. People don't genderize male artists. You know, they don't call them "male artists." I've said this over and over, but we don't call Picasso a male, white painter. In terms of my work, I don't want to be known for my gender or my race or anything. The work stands on its own.

But that's how I look at things. I can't presume my philosophy on other people, but I'm not going to change mine.

AC: Musicians who came to prominence during the Sixties are often asked if their upheaval really changed anything. Do you think that the mid-Seventies punk scene changed anything?

PS: I can't really answer that. It's not really ... it's not my beat. For myself, I wasn't even trying to change things. What I was trying to do was make people aware of things, to wake people up. I think before you can change anything, you have to be awake. That was always what I felt my responsibility was.

There's always change. Some change is for the better. It seems like in everything, whether it's issues on censorship or race or gay rights or hunger, all the things that we're constantly trying to make strides in, we keep going back a little and then we make strides and we go back a little, because there's always new generations, new people who have their own opinions of things and their own way of interpreting things. So I can't really give you a specific, sociological answer, because I'm just an artist.

AC: As an artist, you've just released Gung Ho. You want it to communicate to people. Is there a hope that radio stations are going to open their airwaves to this album?

PS: Well, I hope so. But I'm always optimistic. I always think that radio stations are going to like certain songs. I don't see how they can resist some of the songs that we do. Certainly not on this album. People make the decisions. I'm hoping that people will embrace some of the ideas on this album.

Also, I think that for me, more than any other album, there's beautiful sound on this record. I don't know exactly why some things sound better. Obviously, we had a brilliant engineer and producer. But I really make records for people. I don't make them for the music business or for radio stations. I make them for people and they'll make the decision.

AC: Though I didn't read it, there was a recent unauthorized biography written about you that I heard you didn't approve of. What was it about the book that upset you?

PS: That it was unauthorized. You know, if I'm ready to go though my whole life and share it with people, I'll do it on my own.

AC: You grew up having your share of heroes: Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison. How does it feel now that you're a hero to people -- when they come up to you and tell you how you changed their lives?

PS: It's an honor when people do that. Sometimes it's embarrassing, you know, but not in a bad way. What I always hope is that I've done some kind of work or done something that's inspired people or made them feel less alone. They can use it and then discard it and go do things on their own. I wouldn't want people to be so obsessed with what I did or what my band did that they didn't have their own life. I think they should use it to their advantage and go and be the best they can.

AC: There's a song on Gone Again called "Farewell Reel," for which you wrote, "We're only given as much as the heart can endure." You've suffered a lot of losses since 1989. Do you still believe that statement is true?

PS: Well, I think the human spirit's pretty resilient. I mean, I'm determined to always feel that, because I'm determined to go on as long as I love life. And I'm determined not to let anything beat me down so much that I no longer love it.

Also, I think that our heart is continuously being replenished. Even by the people we lose. I mean, my heart felt extremely dark at a point after my friend Robert [Mapplethorpe] and Richard [Sohl] and then Fred passed away. But when my brother Todd passed away right after Fred, after I experienced the initial shock, what I experienced was that my heart felt light and beautiful and joyful, because that's the kind of guy my brother was. I felt filled with him. So he helped replenish my heart to get it ready for other things it would have to experience. I guess the answer to your question is yes.

AC: You also once sang, "Outside of society, that's where I want to be." Now you're 53 and you've got two kids. Is that still where you want to be?

PS: Well, it seems like that's often where I am, anyway. I'm just that kind of girl, you know.

AC: I was thinking of titling this interview disc One Common Wire. That's a line from your song "Grateful" on Gung Ho. I'm assuming that's about Jerry Garcia.

PS: It was inspired by Jerry. You know I was learning to play the acoustic guitar, and one day I was feeling a little blue, because I was being teased about my newly sprouting gray hairs. And usually, those kind of things don't bother me. But this particular day it, it sort of made me blue. I had sort of tears in my eyes and I was standin' alone. And I shut my eyes for a minute to regroup, and I saw Jerry! I know that sounds really funny, but I saw Jerry Garcia. He smiled, and he tugged on his long, wiry, gray hair and just gave me a wink.

And I opened my eyes and this little piece of music came in my head. I took my little acoustic guitar, and that one of those rare songs that I wrote right off. I wrote the music and I wrote the words without any struggle. And it made me feel better. After I'd finished it, I was really grateful. So I decided to call it "Grateful" in honor of Jerry. And I am. I'm very grateful. ![]()