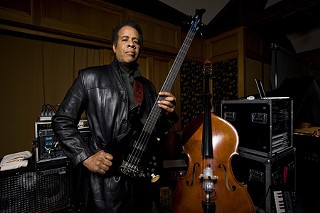

Bomb the Bass

Stanley Clarke, sexy acoustic bassist

By Thomas Fawcett, Fri., May 23, 2008

Stanley Clarke speaks in cool measured tones. That is until you suggest that some find the guitar a sexier instrument than his beloved bass, an instrument Clarke revolutionized with hit instrumental albums like his self-titled 1974 Epic debut and 1976's School Days. It's the guitar, he suggests, that lacks sex appeal.

"The bass is what's happening," he insists.

Clarke, 56, was among the first to realize the four-stringed ugly duckling's swan potential, bringing the bass out of the musical shadows and into the spotlight. Building Larry Graham's slap technique, the Philly-born Clarke transformed the bass guitar from supporting role to leading lady, playing alongside jazz greats Art Blakey, Stan Getz, and Pharaoh Sanders before teaming up with Chick Corea in seminal fusion band Return to Forever. As the RTF lineup fluctuated throughout the 1970s, Clarke remained a permanent fixture. Not even an invitation to join the band of a leather-clad Miles Davis could lure him away from RTF.

Recently his music is heard in movie theatres as often as concert halls, Clarke having written and performed the score for numerous films, most notably 1991's Boyz N the Hood. His latest album, last year's The Toys of Men (Heads Up), is an anti-war anthem that finds Clarke switching between his two loves: acoustic and electric bass. After all these years, they both sound plenty sexy.

Austin Chronicle: How did the RTF reunion come about?

Stanley Clarke: It was actually a very long process. I would say it's technically been going on for over 10 years. In the last year or two, there were some promoters in Europe that made some serious offers for us to get together, and we were talking more, particularly Chick and myself. I met Chick in France, and we decided that we're going to do this thing. It's a funny thing with the band, because all the individuals are uniquely different. I think that's one of the assets of the band besides the good music and work ethic. All the guys are really different from one another. This reunion is going to really be nice. We're doing it in really Return to Forever style. All of us have been practicing and getting our parts together, because the music is demanding even at this point to me.

AC: In the 1970s, there was some turnover in the band, and you had other opportunities come up. What kept you and Chick together for so long?

SC: Chick is a really unique individual. I was remembering the other night, I was playing in New York with a piano player that I played with in the Joe Henderson band – the great saxophonist – and I met Chick when that keyboard player couldn't make it. Joe said, "Look, this guy Chick Corea is going to play with us." Sparks flew, and we hung out later that night and listened to John Coltrane music after the gig. He was telling me about how he wanted to put a band together and how he wanted to present his music, and it was very similar to what I had in mind because jazz was changing at that time. There were younger musicians that were coming into the scene who grew up listening to and loving Miles Davis and John Coltrane, but they also listened to Jimi Hendrix, Cream, and James Brown.

So you had that mixture, and around that time period, those were a lot of the components that went into so-called jazz-rock. The music we did was called jazz-rock, not fusion. Fusion is a term that came later when the bands split off and saxophones and trumpets were brought in. The design and instrumentation of our band was much like a rock band without a singer. We had guitar, bass, drums, some keyboards, and no singer. Chick and I had similar goals. I recorded with lots of other people, but Chick was a guy that I loved to play with. We were both involved in Scientology, we liked similar music, and he's fun to play with. Of all the keyboard players I like, he rates up there at the top. There are a few guys – a Top 5 – that when I play with them, it's killer. I love it.

AC: Who are the other five?

SC: There's Chick, McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock, George Duke, and Hank Jones, Elvin Jones' brother. Those are the piano players I enjoyed playing with the most.

AC: You mentioned the word "fusion." What do you think of the term?

SC: It's a general term. It's a term that you can use to talk about food or about anything. It's also a scientific term. It comes out of science fusing things together, but it's not very specific. Whoever coined that term picked up on the right thing. People can understand it. Usually when music is categorized, the intentions have to do with commerce so they can sell the records. These are fusion records; these are rock records; these are jazz records; this is R&B; this is soft rock. The initial writers and people that interviewed us and reviewed our music – if you go back and look at some of those things – used the term "jazz-rock." That was a little more specific because me, Chick, and Lenny [White] – not so much Al [Di Meola] – we are jazz musicians. That's what we are, and we're nothing more than that.

We understand that we have certain tendencies in other areas like rock and definitely classical, but look at Chick's history. He's played with Blue Mitchell, Stan Getz, and Miles Davis. I played with Dexter Gordon, Art Blakey, and Stan Getz. Lenny played with Freddie Hubbard, et cetera, et cetera. Al was the only guy who was more rock than jazz, but Al had a lot of technique, and even today he's considered a jazz guitar player. Our music was called jazz-rock because we played as loud as any rock band out there, but our solos were jazz solos. We know how to play on changes. We know how to use different kinds of phrasing that you would hear with Coltrane or Davis. We started out playing shows with David Bowie, Bruce Springsteen, Bachman-Turner Overdrive. We did many shows with Fleetwood Mac, all the way up until they had their big album Rumours. We played with Teddy Pendergrass. So we were a jazz-rock band, but when the saxophones came on the scene, the rock went away, and it was easier to call it fusion.

AC: Why did jazz purists and critics have a negative reaction to what you were doing?

SC: Well, because they probably didn't like it. Whenever something new happens, there are people who don't like it. Some people didn't like Charlie Parker; some people definitely didn't like Coltrane. Not to compare ourselves with those guys, but there's a precedent in music history that when something is new, it's easy to stick to the mold. A great example is when Wynton Marsalis came out and all those kids playing with him put on suits and ties and all that, all the jazz critics loved it. To be quite honest, it was almost a carbon copy of the music from the 1960s. The stuff that we did was a stretch; it was different.

Some of the stuff we do is difficult to play. It may not sound it, but it's difficult. Return to Forever, out of all the fusion bands – Mahavishnu Orchestra, Weather Report, Tony Williams, Larry Coryell – our band was more compositional than all those other bands. I think sometimes writers tend to overlook that, but if you listen to it, it was all compositional. It was very well-written, and we spent a lot of time doing it, and a lot of thought went into it. It wasn't just like playing [Charlie Parker's] "Billie's Bounce" and playing the head and then soloing, which is an art, and I don't put that down. At the same time, it's not correct to put down music that's seriously put together and takes skill to do. So, personally, I never paid any mind to it, because I knew that those guys couldn't see it, and that's fine.

Now it's funny that a lot of those critics that hear we're coming back are going to be in the audience. They're going to say, "Man, you guys are great." My thoughts are that music has to move forward. You're really in trouble when you're stagnant. I was very tough on writers and reviewers. I remember Leonard Feather – may he rest in piece – when he was here in L.A. writing for the Los Angeles Times. He loved to talk to me because I would really go to battle with him. I thought he was naive on [fusion]. Just because you don't like something doesn't mean it's not good. It just means it's not your cup of tea. That's what I tried to get through to him, but he didn't want to see that.

AC: The bassline from "School Days" is one of your signature riffs. What are a few basslines from other artists that you really like?

SC: I like the Larry Graham basslines, Sly tunes like "I Want to Take You Higher." I like James Jamerson's basslines on some of the Motown stuff. Even if it's something simple like "My Girl." It's so simple, but it's classic. As soon as you hear it, you know what the song is. That's the thing for me: if I hear a bassline where as soon as I hear that bassline I don't need to hear anything else to know what the song is. Like Anthony Jackson on the O'Jays' "For the Love of Money." You just know right away that's Anthony and that's that song.

AC: Why do you think the guitar is seen as a sexier instrument than the bass?

SC: I don't think it is. If you look at the charts today and music that's on the radio, the guitar has completely disappeared in contemporary music today. To really hear some good guitar players, you have to go to a station that plays oldies, and you may hear a guitar solo. But if you turn on a radio station that plays hip-hop today, you won't even hear the guitar. If you turn on a smooth-jazz station, which are the only stations that play instrumental music, the only time you hear a guitar solo is a little acoustic solo for four bars. So I beg to differ. Maybe it used to be sexy, but I don't know what's happened. They gotta get some new clothes for the guitar, get another look or something. I don't know what happened.

AC: So the bass is big sexy now?

SC: The bass is what's happening. I went to see Marcus Miller the other night, and it was like a bass band, and the place was packed. That was unheard of when myself and Jaco [Pastorius] were on the scene. I had a band, but there were hardly any other guys out there. At one point I was the only touring bass player that had a band. I remember playing a show one time in Indiana, oddly enough, and I'll never forget this. This promoter brought me into a 2,000-seater, and my album Journey to Love had just come out, and the place was packed. The promoter after the show said, "I had to see this to believe it." It was like it was an illegitimate gig or something. It was really funny. It didn't dawn on him that a guy that played bass could stand at the front of the stage. I was thinking about that the other night when I saw Marcus. You can hear every single note that he plays, and I just thought it was great. That's just really cool. The bass has made the biggest leap in instrumental music in my opinion. When I started out, there was only a handful of guys that made albums, and now there's over 1,000 bass albums out there. I can't say they're all good, but they're out there.

AC: How does your technique change when you go from the electric to the acoustic bass?

SC: For me it's a totally different instrument. Electric bass is a guitar. It's a guitar technique with bass sensitivities. There's a lot of cool techniques with the slapping and the tapping and all that. The acoustic bass you think about the same way you do cello and violin. It's Old World European, and to play it correctly, you have to go through that curriculum. The fingering is different on the acoustic. It's a totally different instrument to me.

AC: You've collaborated with everyone from Art Blakey to Pharaoh Sanders to Chick. Is there anyone out there that you haven't played with that you'd like to?

SC: No one that I can think of. But I wouldn't mind dancing with Beyoncé.

Return to Forever slaps, taps, and debuts its reunion at Austin's Paramount Theatre, Thursday & Friday, May 29 & 30. Somebody invite Beyoncé.