Le Grand Fromage

Whole Foods' global cheese buyer, Cathy Strange

By MM Pack, Fri., Nov. 2, 2007

Tyrophile. It means "cheese friend" in classic Greek. In its 20th century American form, turophile, it's what you call someone who loves cheese.

Cathy Strange, the global cheese buyer for Whole Foods Market, has got to be one of the best friends that cheese has. From the Austin corporate headquarters, Strange orchestrates all cheese operations for the far-flung Whole Foods enterprise – she travels the world in search of the best artisan cheeses and works with farmsteads, cheese-makers, and affineurs (skilled cheese caretakers) to supply all the Whole Foods stores in the United States, Canada, and Britain. She's a tireless advocate and supporter for traditionally made cheeses that reflect their regions and seasons, the animals that contribute the raw material, and the artisans who craft them.

If you have visited Austin's Whole Foods flagship store, you can attest that the cheese display can be richly overwhelming: literally hundreds of cheeses reflecting every style, flavor, texture, color, and origin. Multiply that experience by Whole Foods' 11 regions and 194 stores to get some idea of the scope of the cheese world that Strange inhabits. "I'm personally acquainted with where each of our cheeses comes from and who makes them," she says with quiet confidence. Considering that WFM carries more than 100 national core cheeses plus 250 to 700 additional cheeses chosen regionally for individual stores, that's a lot of cheese, a lot of knowledge, a lot of relationships, and a great deal of culinary traveling. Sounds like a turophile's dream.

Cheese in These United States

If you spend even a little time with Cathy Strange, it's impossible not to be infected by her enthusiasm and vast knowledge; you can't help but absorb good information about cheese-making and what's going on in today's world of cheese.

"Within the past decade, there's been an explosion in America regarding cheese," Strange explains. Why now? Through the 19th century, there were hundreds of American cheese-makers, but the fate of cheese-making paralleled the dwindling fortunes of family farms, and industrialized cheese became the norm for most of the 20th century. Cheese in the U.S., synonymous with Kraft, was young, bland, and nondescript, with some exceptions in Wisconsin, New York, Vermont, and California.

However, as more Americans traveled overseas during the Sixties and Seventies, they discovered the joys of European cheeses and demanded better and different styles for American cheese. The trend has only continued to grow, fueled by increasing interest in nonindustrial food. According to a recent article about artisan cheese in Condé Nast Portfolio, the specialty-cheese market (including U.S. and foreign products) is worth $6 billion, and the demand for artisanal and farmstead cheeses increases by 15% annually, faster than any other dairy-market segment.

Strange talks about the American "goat cheese revolution" of the Seventies, with women in the forefront. "In those days, the best cheese-makers were breeders of goats, although that's not so true now." Some of the pioneers – Judy Shadd of Capriole in Indiana and Jennifer Bice of Redwood Hill Farm and Laura Chenel, both in Sonoma – remain goat-cheese rock stars today. Why women and goat cheese? Strange speculates that it was easier for women to manage goats than cows and that they might be more likely to share husbandry and cheese-making information. She says, however, that "it's difficult to both raise animals and make cheese; you almost have to specialize in one or the other." That's one reason why savvy turophiles honor farmstead cheese: It's such a challenge.

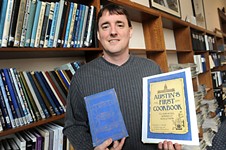

Photo courtesy of Cathy Strange

In Europe, artisan cheese-making has a venerable history, although there, too, market forces threaten small producers' survival. Nonetheless, regional, handmade, and farmstead cheeses are well integrated into traditional food cultures, terroir-based individuality is appreciated, and the role of affineur is a respected profession (this is the patient, trained expert who buys young cheeses from producers and then properly cares for them as they mature). Strange says that these ideas and practices are increasing in the U.S., but Whole Foods "imports because of the great variety and traditional nature of European products. We just don't have the same depth of cheese history here." She estimates that half of her cheeses are domestically produced and half are imported, primarily from France, Italy, Switzerland, the UK, and Spain.

Becoming the Big Cheese

Strange has worked for Whole Foods for 16 years but has lived in Austin only since November 2006. She's pleased to find such commitment here to sustainability and local eating and is impressed by the restaurants. She views Austin as "a pretty dynamic place; there's lots of artistry everywhere, including the food. There are two international languages, music and food. Everybody eats; everybody listens to music. Austin is so dynamic in both areas."

Strange's entrée into food and wine 24 years ago was something of an accident, albeit a happy one. "I grew up in a military family with five kids," she says, "and food wasn't particularly a big deal for us. I was a picky eater, and I probably didn't really experience homemade good food until my 30s."

After graduating in education from the University of North Carolina, Strange taught and coached sports for eight years at Florida State and the University of Tennessee. In 1986, she moved to Durham, N.C., to be near her ailing mother, taking a "temporary" job at a friend's restaurant that evolved into eight years of being sous chef and manager. "I was inspired by the commitment and energy in restaurant people," she recalls. "My eccentric boss was first-generation Italian, so passionate about food."

After the restaurant closed, Strange worked for the American Social Health Association but missed working with wine. She took a part-time job in 1993 in the wine section of Wellspring Grocery, "the Dean and DeLuca of North Carolina natural food," and one month later, Whole Foods bought the store.

Strange's career at Whole Foods took off. From part-time wine person, she graduated to in-store restaurant manager and then specialty team leader (wine, beer, cheese, coffee, and housewares). She helped open new stores in Washington, D.C., and by 1996 was the regional specialty coordinator for a five-state area.

When the global cheese-buying position opened in 2001, it was tailor-made for Strange. The new job was created "because the stores were all over the board with cheese. The purpose was to ensure the highest cheese quality everywhere and to leverage buying."

An example is Parmigiano Reggiano. "Different stores used to purchase it from wherever. Now we buy hand-selected cheeses aged 24 months from five farms in Italy, made with spring and fall milk. The quality of Parmigiano Reggiano is the same in every Whole Foods." Purchasing of imports is built around Denomination of Origin cheeses that meet the regulations of each region: Blue D'Auvergne is raw-milk cheese from Auvergne, France; Morbier is raw-milk cheese from Jura, France; Manchego is from La Mancha, Spain; etc.

To complement imports, Strange says, Whole Foods is committed to supporting and stocking regional specialty cheeses. "In every Whole Foods store," she says, "you'll find cheeses from that area [except in Florida]. This is a requirement."

What Does a Global Cheese Buyer Do?

Photo courtesy of Cathy Strange

Every day, Strange works with cheese coordinators for Whole Foods' 11 regions, as well as directly with farms, cheese-makers, and suppliers, here and abroad. "It's like running your own business inside the corporation," she says. "Much of what I do isn't romantic tasting and travel. I spend a lot of time looking at spreadsheets and reviewing financial performance." (But she still personally unpacks and tastes cheeses that arrive at the Austin store.) She developed the online employee-training about cheese, and she's involved with the Whole Foods' Local Producer Loan Program, which provides microloans to small producers. "We're committed to keeping producers in the business they love; if their cheese meets our quality standard, we'll do what it takes."

When on the road, which is often, Strange routinely inspects cheese-production facilities and warehouses. "If a cheese is in the stores, someone from Whole Foods, probably me, has visited its production site," she says. "Also, I try to go to a different store at least once a month."

On her last trip, Strange attended a company cheese coordinators' meeting in California and flew to Italy to attend the Slow Foods International Cheese Exhibition in Bra ("the premier cheese show in the world") to meet with producers, attend seminars, taste cheeses, and source new products. She drove to Roanne, France, to visit the caves of renowned affineur Hervé Mons (see "Cathy Strange's Seasonal Cheese Picks"), then took the train to Paris to see a new international cheese consolidation warehouse. From there, she flew to Cork, Ireland, to tour cheese facilities and then flew back home. All in 15 days. Whew.

"To do my job," Strange says, "I need to balance the analytical side with a passion built around producers and partnerships, along with a lot of love for the products."

Cheese Activism

Not only is Strange instrumental in the Whole Foods cheese culture; she is active in a variety of cheese-centric organizations, national and international. She's past president of the American Cheese Society, founded in 1969 to support cheese education and promote quality cheeses produced in America (see "Guide to American Cheese Organizations and Competitions"). She regularly serves as a judge in the annual competition, where entries are evaluated on aesthetics (flavor, aroma, texture, and appearance) and technical, dairy-science standards, last held in Vermont in September, where there were 1,400 entries. Strange says this indicates how much and how quickly specialty cheese-making has developed in this country. "At the ACS competition 12 years ago, all the entries fit on two picnic tables."

In January 2006, Strange was inducted into the Guilde des Fromagers/Confrérie de Saint-Uguzon, the prestigious French cheese association that supports the cultural and historical significance of quality cheese-making and encourages and facilitates traditional methods of cheese production. She's one of the few American members.

Strange also supports the Cheese of Choice Coalition and the Raw Milk Cheesemakers' Association (see below), consortiums that promote the production and importation of raw-milk cheeses, working with the Food and Drug Administration on U.S. standards. And it goes without saying that Strange and Whole Foods are committed to supporting organic and bovine growth hormone-free products.

Advice for Cheese Lovers

Cheese business aside, Cathy Strange has a few words of advice about eating and enjoying cheese. "Never be afraid to ask a vendor to cut a piece from a wheel," she says. "Don't hesitate to touch, smell, and taste. Experiment and try new cheeses; we all know we like certain flavor profiles, but you can be pleasantly surprised by something new."

"Only buy cheese you can eat in a few days," she continues. "When you get it home, remove the plastic and wrap it in paper or waxed paper. Keep cheeses cool and away from flowing air." And finally, "Eat it up, and cook with the leftovers!"