Shrinking Schools

While the suburbs sprawl, central city schools count their children – and their blessings

By Rachel Proctor May, Fri., May 20, 2005

First came five young Marines, guns and flags erect. Then came the UT band, skipping and waving their horns. They were followed by the very best readers at Zavala Elementary: sixth-graders in tiaras, fourth-graders blowing kisses, a jeep full of little kids spilling out over a hand-painted Leer es Poder sign. As the parade moved past, clumps of students lined up along the sidewalk joined in, until the entire school, plus moms and dads and grannies galore, was parading together down East Third Street in the school's 10th annual Reading Rally.

Among the moms in attendance was Dolores Perez, who wouldn't dream of missing a reading rally. "This is something the whole community takes pride in," she said. Toting a lawn chair, she found a place before the school's mural-adorned amphitheatre and readied her video camera to capture the next hour of cheering, chanting, singing, and dancing in honor of the written word.

Perez attended Zavala, her sixth-grade son attends Zavala, and she's proud as heck to be part of the Zavala community. It's the kind of school that it's sometimes easy for Austinites to forget exists – a good school on the Eastside. Its test scores (if you're into that sort of thing) aren't the greatest, but it's a place where teachers value creativity, where parents turn out in droves for events, and where kids can walk a few shady blocks and hang out with grandma after school.

It's also the kind of school whose future is uncertain. All over East and Central Austin, elementary school populations are flat or declining, even as outer-fringe schools are bursting with children. Of AISD's 74 elementary schools, 19 are already below 75% capacity, nearly all in central locations. Demographic projections suggest that several, such as Campbell, Oak Springs, Allan, and Ortega, will likely shrink further. When most schools on the fringes are full to overflowing – a dozen are at 120% of capacity – these numbers are striking.

On the one hand, the numbers tell a story of gentrification: Lower-income families move to the suburbs to buy double the house for half the price, and are replaced by childless couples, empty nesters, and middle-income families with one child or two, rather than three or four. They also tell a story of sprawl: Inner-suburban school populations plateau when neighborhood kids grow up and younger families choose neighborhoods even further out. Of course, housing trends involve dozens of factors (apartments, for example, usually pump out a fresh batch of kindergarteners each year no matter what neighborhood they're in) so the story they tell will always be complex. Overall, however, their story is one of center-city schools scrambling – even competing – for students.

Outer-fringe overcrowding is a much bigger problem for AISD than shrinking schools. In the short term, beyond adjusting boundaries and finding creative ways to make use of underutilized space, there isn't much AISD can do directly about declining student populations. For individual schools, however, student loss can affect staffing levels, funding, and morale, especially when student transfers to other schools add to the decline. While principals and parents in transitioning areas can't stop gentrification, some hope to take advantage of it – by convincing neighborhood newcomers that an East Austin address doesn't have to mean educational inferiority.

Judging by the Numbers

Ortega Elementary is one of the easternmost schools in AISD. The drive out Ledesma Road, east of Springdale, passes tiny cottages with elaborate yard art and overflowing garages, suggesting that most folks have been living here a long, long time. Approaching the school's wide, sunny grounds, two houses stand out on a wooded hillside to the north. They're brand new, three times as large as anything nearby, and painted in tasteful pastel tones. Change is coming to the Ortega neighborhood.

Meanwhile, change has already come to Ortega. When the final bell rings at 2:45, a few dozen parents gather beneath the school's front awning to meet their progeny. Ortega's student population is drifting downward, to be sure – it's dropped a few dozen students in recent years, with demographic projections showing future decline – but the parents milling around describe a new life in the long-struggling school.

Robin Henry and Randy Todd credit the change to principal Anna Pedroza, whom everyone calls "Dr. P.," and assistant principal Monica Woods, both of whom joined the school this year. As they await their fourth-grade daughter – an impish redhead who wants to be president, a writer, and an artist – the couple describe themselves as "happy for the first time" since their daughter started pre-K. Their daughter "made a painting and it got into an art show. She wrote a poem and it got published. That's the kind of support they're giving her," said Todd.

PTA secretary Nikisha Yarbrough also sees the change. She says parent involvement is on the rise, with about four dozen parents regularly pitching in. ("That's still not enough," she said.) Yarbrough was born in the neighborhood and attended Ortega as a child, and though she's moved elsewhere, her mom is still here, so she still sends her second-grader to the school. She says a lot of the kids she grew up with are doing the same. "The elders are still here, so that brings us back to the neighborhood," she said. "Ortega feels like home."

Another sign of change, Yarbrough says, is this year's revival of the fundraising carnivals Yarbrough enjoyed as a kid. The event included a silent auction – teacher-baked pies, a picnic with Dr. P. – and it raised about $1,700 for the PTA. They'll spend it on books for the library, classroom supplies, and shoes and eyeglasses for children whose families can't afford them.

Almost all of Ortega's students – 92% – are poor. This is not unusual in AISD, where economic segregation is the norm. Of AISD's 74 elementary schools, 43 have student populations of more than 79% "low socioeconomic status" (known in demographer-speak as "low SES"). Another 14 have less than 20%. Only 17 have anything approaching a mixed economic demographic. Not surprisingly, it's the well-off schools that earn the "exemplary" ratings from the Texas Education Agency.

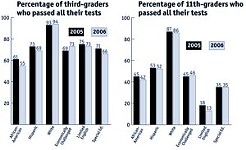

But even though most majority-poor schools earn the mediocre rating of "acceptable" from the TEA, that one-word rating obscures the tremendous variety among "acceptable" schools. Here's how it works: While it's common to talk about schools with "high" or "low" test scores, schools don't actually earn TEA ratings – "exemplary," "recognized," "acceptable," or "unacceptable" – based on how well students do. Rather, the ratings reflect the percentage of the student body that passes each test. A "recognized" school, for example, is one where at least 70% of students pass on every test given. They may barely pass, or they may earn a perfect score – it doesn't matter to the rating (nor to the Capitol test-mavens). In addition, one ethnic or economic group's poor performance on one test in one grade will bump down the rating for an entire school. For example, if only 69% of white students pass the third-grade reading test, the entire school will be rated "acceptable," no matter how well all the other students do on all the other tests; the same will be true of minority or low-SES percentages. This is based on the sound idea that schools shouldn't be able to hide the poor performance of some by the strong performance of others; on the other hand, it also means that trouble with one test can make a school look worse than it is.

That's what happened to Ortega last year. Standing in a hallway decorated with construction-paper portraits and science-project displays, Dr. P., a short, dynamic brunette, proudly shows the colorful graphs of TAKS scores pinned to the bulletin board across from the office.

"We would have been 'recognized' if it weren't for science," she said, with a proud tap of a salmon-colored fingernail on the scores. (Ortega's not alone there – without the science test, which was brand new last year, the number of "exemplary" or "recognized" schools in AISD would have more than doubled, from 23 to 57. In response, AISD spent the year beefing up its science curriculum, which is something even critics of standardized tests can appreciate.) Still, Pedroza said, the campus has many needs that the declining population makes it hard to fill.

AISD staffs elementary classrooms at a 22-to-1 ratio whether there are 22 students or 800. However, shrinking schools are squeezed in other ways. As Ortega's population declines, the school gets a smaller percentage of the district's Title I funds (federal money to support low-SES students). Plus, this year the population fell below 300 students, AISD's cut-off for providing a half-time assistant principal. After much thought, the campus advisory committee decided to use about half the school's $100,000 Title I money to pay for an assistant principal. "We missed 300 by less than 10 students," said Pedroza. "That doesn't take away our needs."

Indeed, Ortega's needs are many, and funding the assistant principal leaves less money for things like library books and field trips. But, says Pedroza, "short of praying that 10 more kids show up," that's all they can do.

Nevertheless, Pedroza stresses that Ortega's small size has its advantages as well. After all, the hot new concept in education is breaking large schools into smaller "schools within schools" as a way to build personal relationships that, in theory, inspire success. With such a small community, Ortega already has that – teachers can get to know their students' families, and many walk over to their students' homes after school for informal meetings with their parents. "As long as the district doesn't move toward closing or consolidation, Ortega will continue to thrive," Pedroza said.

(Despite fears and intermittent rumors to the contrary, consolidation – combining small neighborhood schools into larger regional ones – is probably a long way off for most of Austin's shrinking schools. For one things, AISD recognizes that many of its most successful schools are the small ones. And, outside of the cost of a principal and building utilities, consolidation doesn't really save much money. Students need essentially the same number of teachers whether they're in one school or two; plus consolidation comes with costs of its own, like providing transportation to former walkers. "A lot of people think there's a pot of gold at the end of the school-closing rainbow, but that's not the case," said AISD planning director Dan Robertson.)

Still, a loyal community and strong relationships can't do everything. Pedroza sees the neighborhood aging as families move away, buying brand new three-bedroom homes for $90,000 in Buda. While some, like Yarbrough, use their elders' presence as a way to stick with the school, others are gone for good. Nevertheless, Pedroza has no doubt that if new families do start to replace the elders that now dominate the neighborhood, they'll value her school as much as the current residents do. "As long as I keep my focus on the high academic performance," she asks, "why would you want to send your child somewhere else?"

People Will Talk

A blue-ribbon banner proudly hangs over the brick facade of Blanton Elementary in northeast Austin: "2000-01 Texas School of Excellence," it says. The 625-student school is a few blocks north of 51st Street, and the accelerated rumbling of cranes and trucks at the Mueller redevelopment are sending reverberations through the neighborhood. A run-down, 1,200-square-foot house that two years ago went for $90,000 today can't be had for less than $130,000. Even those are hard to get your hands on: Many get snatched up by investors, who gussy them up for the hardwood-floors crowd and relist them in the $170K range.

Blanton Principal Leslie Dusing didn't think much about the change in the neighborhood until she happened, by chance, to glance at this year's transfer numbers. She found that 47 students from the Blanton attendance zone had departed, their parents choosing schools across the highway, like Bryker Woods or Lee. Since Dusing was used to Blanton being the "good school" in the neighborhood – the one that received transfers from struggling nearby schools like Pecan Springs or Harris – that shocked her.

"It would be one thing if this was a low-performing school with issues," Dusing said. "But this is a national blue-ribbon school!"

Forty-seven students moving about in a district of 78,000 isn't likely to alert the radar of a central office planner, especially when nearby apartment complexes will keep many of Blanton's classrooms full. But to Dusing, who looks out the window and sees tiny postwar homes pushing $200,000, it's handwriting on the wall. Now, she says, her "crusade" is to bring the neighborhood's new homeowners into the school before "Nobody goes to Blanton" becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

If a parent from the neighborhood were to ask Dusing to explain why they should enroll in Blanton, another of AISD's "acceptable" schools, rather than a high test-score school across the highway, she would take them to the school's peaceful courtyard with the Japanese-style pond, where the students raise goats and chickens and fuzzy white rabbits. She would tell them about the fully equipped science lab, the gifted and talented program, and opportunities for bilingual education. If they were to ask about enrichment, she would tell them about African drumming, and after-school golf, or the elaborate two-camera newscast of school announcements that different groups of students produce each morning.

But she can't tell them, because nobody asks. "When I looked at the list of those who had left, only one had come by to see the school," she said. "I want the opportunity to at least show the quality education we offer."

One parent who saw the quality – once he looked – was Martin Luecke. Like many of his neighbors, he had transferred his daughter and son to Bryker Woods, and was perfectly happy until his son, then in fourth grade, lost his transfer. "The day I found out, I thought, 'Holy smoke, we actually have to go to Blanton,'" Luecke said. "When we walked in I realized I'd never been inside the school except to vote."

Luecke has been thrilled with Blanton, and says his son is succeeding like never before. Still, he sees reasons the school might not be for everyone. For one thing, "high-poverty" (89% low-SES) and "high-minority" (80% Hispanic, 15% African-American, and 5% white) are not synonymous with "diverse," if that term means a wide range of races and economic levels. "My son is the only white kid in fifth grade," said Luecke. "A lot of parents wonder, 'Can my kid handle that?' My son can handle it." (Although it's a random and isolated incident, the handgun brought to Blanton by a 5-year-old on Tuesday – now in heavy TV rotation – isn't going to help Dusing make her case.)

In the eternal debate between those who believe in neighborhood schools in principle and those who prefer to shop around, the question of white flight is never far off. Still, AISD's transfer data paints a complicated picture. About 12% of AISD students transfer; their racial composition almost precisely equals the district's. Students come and go from every school in the district, even the most desirable ones – Highland Park kids transfer to Casis, Casis kids transfer to Bryker Woods, Bryker Woods kids transfer to Lee, and so on – and few schools show a net in- or out-migration.

Parents decide where to go based on zillions of factors, from location to the principal to teachers to the feeling they get when they walk in the door. Word of mouth, however, is huge – Deb Lewis, a parent who has yet to set foot in a single AISD school, says she already has plenty of other people's opinions to mull over.

"There's a buzz that certain schools have certain traits," she said. "People call Highland Park 'the homework school.' They call Lee 'the Shakespeare school.' They say Gullett has a good sense of community and the kids go outdoors more. You hear it enough, it starts to become some sort of truth."

While word-of-mouth helps parents shop, some complain that the buzz doesn't always reflect reality. Brentwood, a racially and economically diverse school in North-Central Austin, suffers a mass exodus of students to whiter, wealthier Gullett each year – 61 students this year, out of a population of just under 400. While some have specific reasons for leaving – one parent, for example, tried Brentwood but left because she felt school leaders didn't welcome parental involvement – PTA president Pam Johns believes many never gave the school a chance.

"A lot of them never even come and visit Brentwood," she said. "I think their impression is that Brentwood is not as good of a school, and that we have problems that Gullett or Bryker Woods don't have because of their more homogeneous population."

Ironically, nearly as many students transfer into Brentwood (92) as out (105). Still, when neighborhood demographic change has also left Brentwood only two-thirds full – it's built for 600 – the school could use some of those migrants back. While Brentwood actually gained about 30 students this year, its underenrollment is starting to have consequences. This spring, for example, a group of parents attended an AISD board meeting to plead to keep their "art cottage," a portable they had painted blue and planted flowers outside, and which the district wanted to move to a school with greater need for space. AISD eventually relented, and the art cottage will remain. Still, with the transfer snowball in motion, Brentwood parents worry the battle won this year could be lost the next if they don't hang onto neighborhood kids.

Of course, Gullett, like most schools in pricey, aging West Austin neighborhoods, needs kids too. In fact, without its 175 transfers (40% of the student body), Gullett would be in Brentwood's underenrolled shoes. Another outgrowth of shrunken schools, then, is competition for the students that remain. In that battle, it's the schools with the best buzz that win.

Building the Buzz

Some schools have positive buzz, some have negative, and some simply have no buzz at all. When parent Darrel Mayers, who lives near Blanton but whose home school is Harris, started shopping schools, other parents' opinions helped shape his list, which included Bryker Woods, Lee, Pease, and a private school. Blanton, he said, was simply never on his radar screen. "The Eastside is not necessarily known for its great schools," Mayers said. (He settled on Lee, which he loves.)

Not all Eastside schools are good; indeed, many are truly struggling. However, the word-of-mouth phenomenon means that even successful schools in transitioning areas can have trouble getting noticed by newcomers. And given the wide range of traits that different parents look for in schools, simply getting noticed may not be enough.

Every parent defines a "good school" a little differently. Even as some look for that "exemplary" rating, others look for schools that promise to keep standardized test-prep to a minimum. Parents often look for other involved parents, or cool opportunities for enrichment. Immigrant parents may look for a strong bilingual program. Still, it's hard to ignore the role of economic demographics in middle-class parents' decisions. In addition to the tangible benefits that better-off parents provide – not many PTAs have a $294,000 budget like the popular transfer destination Casis – affluence is also a reflection of parents' own educational levels. As an AISD teacher, Tom Ball knew Blanton's strong reputation but transferred his son to Lee, which is near UT and attracts a lot of university types, in part because of the other students' backgrounds.

"It was important to us that he would be with a lot of academic-minded students, where the level of expectations would be higher," he said. "Peer influence is a real strong shaper of how a kid does." (In addition, Ball pointed out that Blanton kids move on to Pearce Middle School and Reagan High, whose dangerous reputations can scare off even the most zealous neighborhood-schools crusader.)

However, as the wave of gentrification washes eastward, it's precisely that peer influence that Dusing wants to reinforce at Blanton. After all, AISD does have a handful of schools that are both racially and economically diverse, have only "acceptable" test scores, and parents love them anyway. Zilker, for example, is about half poor, roughly mirrors the district's demographics, and accepts so many transfers it's operating above capacity. Maplewood, east of the Fiesta Mart on I-35, and Mathews on West Lynn have similar demographics and inspire similar loyalty.

Perched on a chair in her colorful office, a knickknack extravaganza with a tinkly Zen fountain and shelves overflowing with stuffed animals (pigs on one wall, frogs on another), Dusing mulls her options. She could go to neighborhood meetings. She already tried inviting families that planned to transfer on a school tour, to no avail. She recognizes that she has a hard road ahead, especially when the school was low-performing not so long ago. But with a new principal and almost all new teachers, what matters, Dusing says, is Blanton's performance today. "The district has poured resources of every kind into these East Austin schools," she said. "Many of them have improved. And I think it's a shame not to have people come back."

Small Victories

Sometimes, they do come back.

In the late Nineties, Travis Heights Elementary had nearly 700 students. Although it's located in one of the priciest parts of town, Travis Heights is also a few blocks from a Section 8 complex, so the school is 70% poor and ethnically diverse.

Around 2000, students – mostly middle-class ones – started leaving. It was a time of chaos – the school went through five principals in two years, and had to move all the students out for mold remediation. By 2003, the school was down to 457 students. New principal Lisa Robertson recruited several parents who had stuck with the school to reach out to others. They held house meetings, and invited prospective parents to the school for play dates and coffee chats and pre-K.

It looks like it worked. On this May's Kindergarten Round-up, the day AISD schools enroll their new class, parent Steve Jackobs, who had been front and center in the parent-recruitment effort, was ecstatic. "There are three times as many people here as last year!" he said; the school expects 580 students this fall. Granted, Travis Heights has an easier job than East Austin schools – it was trying to win people back, not attract new neighbors who had never been there in the first place. No one at Travis Heights had to feel like a "pioneer" or a "guinea pig."

Still, as Austin neighborhoods evolve, Travis Heights' recruitment success – plus the continued desirability of AISD's other racially and economically diverse schools – provides some hope. After all, some gentrified neighborhoods are seeing something of a baby boom among the newcomers. If those young parents decide to stay put en masse, rather than migrate en masse, some of the best East Austin schools may emerge from gentrification as strong as ever, with a new population of middle-class kids to add to their diversity.

Of course, the fact that fewer kids are being born in much of central Austin absolutely dwarfs the issue of where their parents choose to send them. Schools like Barton Hills, Lee, Gullett, and Bryker Woods – about half transfers each – woo transfers in part to make up for the largely child-free demographics of their own neighborhoods. And, it's not the elementary school loss, but the loss of students between fifth and sixth grade that district demographic reports calls "particularly alarming." Yet, for those schools located in increasingly diverse neighborhoods, capturing that diversity nevertheless seems a valuable goal.

Back at Zavala, Dolores Perez watches the young readers cheer and chant. All the teachers are in paper cheerleading skirts, and they fling themselves through a series of kicks and chants with engagingly more passion than talent.

Perez has seen new people coming to the neighborhood, ones who didn't go to Zavala as children, and who don't know anyone who did. Two blocks away, for example, right across from the UT charter school, a brand-new mixed-use development is going in. It's part affordable housing, and part "market rate." What changes like this mean for Zavala, Perez isn't sure. Still, she says, the newcomers are coming, and the community must embrace them.

"We need to welcome them, like we welcome them in our own homes," she says. "Working together we will accomplish more." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.