Urban Tejano

Grammys beckoning, Tortilla Factory reopens for the next generation of business

By Margaret Moser, Fri., Dec. 24, 2010

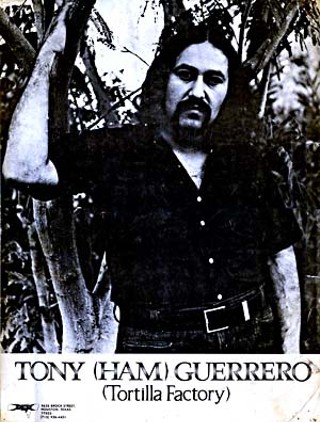

Tony "Ham" Guerrero's story begins in San Angelo, the real cotton fields of Western songs. Its chapters are soundtracked by time-worn vinyl records – treasured artifacts of another age. Illustrated by a half-century stash of photos, posters, clippings, and mementos, Guerrero's tale embodies Chicano pride told through family and band.

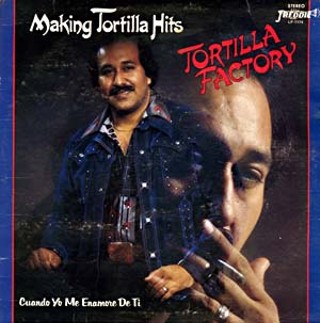

Tortilla Factory birthed a new kind of Latin soul from 1973 into the 1980s, somewhere between Doug Sahm's Westside San Antonio gang and Santana. Funkier than but closely related to the 1960s Latino hybrid of Chicano soul (see "A Browner Shade of Black," Dec. 28, 2007), Guerrero, the trumpeter, built red-hot rhythms, white-rock influence, and brassy Tejano melodies into one explosive sound. Tortilla (as the band's affectionately known) even claims roots with the kings of Texas Tejano, the legendary brothers Hernandez, Little Joe and Johnny. Finally, Tortilla Factory slapped down its very own trump card in ace singer Bobby Butler.

By the late 1980s, Tortilla Factory posted a "closed" sign. Age and time had taken its toll, and trends in music shifted elsewhere. Guerrero and his family operated a club in Downtown Austin – Club Islas – for four years. And like the seasons and fashion, what goes away usually cycles back around in one form or another.

Guerrero reopened his Tortilla Factory in 2000, reuniting with Butler and introducing his son Alfredo Antonio Guerrero into the band six years later. Their 2008 CD, All That Jazz, received a Grammy nomination – grand affirmation of his decades of work. When Guerrero's health buckled, Alfredo stepped up and took over, bringing in a secret weapon: his sister Laura. Alfredo and Laura now reinvent their father's once-revolutionary sound with contemporary beats that sizzle on Tortilla Factory's 2010 release, Cookin.

Topping it off early this month, Tony "Ham" Guerrero received an early Christmas present. Cookin landed Tortilla Factory its second Grammy nomination for Best Tejano Album.

The Tejano Freddie Hubbard

Tony "Ham" Guerrero's North Austin abode houses tales of untamed musical youth.

His chair backs thronelike to a dark wood-paneled wall that splays out various framed photos and awards like rays of the sun god. He and Bobby Butler were inducted into the Tejano Roots Hall of Fame, and he's recognized as a Pioneer of West Texas Music at the West Texas Hall of Fame. Certificates and awards also honor his wife, Norma, named Bilingual Teacher of the Year in 2002 for Texas. "She oversees all our compositions and corrects all the grammar," chuckles Tony with great affection.

At 66, he's a handsome old lion, his once-bushy mane tamed into a ponytail. Talking with oxygen tubes in his nostrils, his breathing is as measured as his phrases, wheezing faintly. He tilts his head toward the speaker, musician-deaf, but the memories are sharp, clear, and being coaxed out for his autobiography.

Guerrero developed his musicianship first on the cornet at 8, and by the age of 12 he was playing with the San Angelo Symphony. During his teens he won gold medals in university competitions, began playing in local bands, and studied trumpet with Pablo Martínez in Houston. He was offered a scholarship to Berkeley and recieved an education in San Francisco by day while playing salsa at night.

"They called him the Tejano Freddie Hubbard," notes local trumpeter Jeff Lofton, repeating the oft-cited comparison. "I got a chance to sit in with him. He had the tightest group!"

Emphysema robbed Guerrero of his ability to perform with Tortilla Factory on a regular basis, so now he manages and produces the band, a role he's content with but admits to still singing a little and sometimes picking up his horn.

"We almost lost him a while back," admits Alfredo Guerrero, leaning over and offering to help his father settle into the chair. Tony Guerrero rebuffs him.

"My dad gets that name 'Ham' for a reason," says Laura Guerrero, grinning as she relaxes on a nearby sofa. "You sit here an hour, and he's got you laughing, just being himself."

Her father smiles. He still hears a great deal. He's seen even more.

Arriba

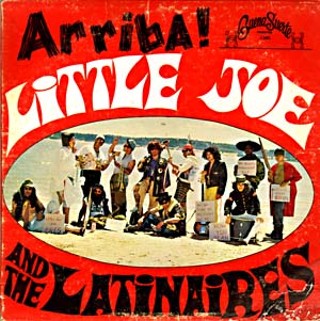

The year 1967 marked Tony Guerrero joining Little Joe & the Latinaires as a young-buck trumpeter. Many young players had broken away from the old-school Latino bands that wore matching suits and greased back their hair, harmonizing to songs their parents loved. Latin music had long held sway with rock & roll, even before Ritchie Valens or the Champs' "Tequila," but the 1960s colored it anew.

The marching, charging call of Latino garage rock in the mid-1960s issued most famously from California with Cannibal & the Headhunters' "Land of 1000 Dances," in Saginaw, Mich., with ? & the Mysterians' "96 Tears," out of Dallas with Sam the Sham & the Pharaohs' "Woolly Bully," and via San Antonio with the Sir Douglas Quintet's "She's About a Mover." Much of this music was driven by the Vox or Farfisa organ, hip replacements for the unhip accordion. The Latino-based organ sound echoed across rock & roll and entrenched itself in psychedelia.

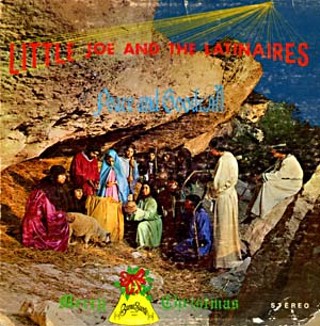

This Texcentric beat was echoed by countless Latino touring bands of the day, Little Joe & the Latinaires among them. The Latinaires, wrote Sunny Ozuna of the Sunliners in liner notes for vinyl recording Arriba, were "a combination of Latin soul and English variations." A few years later, he might have called it Tejano. The band's charismatic stage presence in the form of Temple-based singers and brothers Joe and Johnny Hernandez made them formidable and hugely popular.

From their home base in Temple to the nonstop circuit of fairs, weddings, dances, and events, Little Joe & the Latinaires toured the U.S. constantly. Guerrero's collection of vinyl records speaks volumes that go to 11, archived in worn cardboard carrying cases. Here's the Latinaires, dressed in matching suits and slick coifs, arranged for a studio pose with stiff expressions, clowning for the camera, surrounded by women. Here's Tortilla Factory, sometimes 10 pieces, sometimes just a photo of Guerrero. Here's La Familia Inc., precursor to Tortilla Factory: Guerrero with Johnny Hernandez and producer Luis Gasca. They're young, handsome, virile, flaunting hair long in curls and 'fros, hirsute displays of mustaches and beards, dripping with testosterone in their proud stance atop la Onda Chicana.

For the Latinaires, touring meant making money, a small fortune largely frittered away on high living and fast times. The Latinaires played night after night, accruing untold amounts of cash, according to Guerrero.

"Little Joe would send me sometimes to pick up the gate," he waves. "Once at San Jose Fairgrounds on a Thursday night, I was too stoned, but the manager wasn't there so I went to get the money – $17,000, in cash. In 1971. That was every night. Some nights it was $25,000 or $30,000. I wish I hadn't been such a fool financially"

In 1973, Little Joe "fired us, the whole damn band. Too many snobs – he thought we weren't listening to him." The pink slip from the Latinaires stung, but it turned out to be Guerrero's ticket to the Tortilla Factory.

The 'M' Word

Tortilla Factory suffered growing pains early. In 1974, half the original members quickly left while the other half relocated to the Bay Area with Guerrero. The bandleader rounded up a new lineup for his vision of Tejano, a muscular cross section of rancheros, boleros, and the occasional polka, with thick threads of rock and jazz. They thrived, and the good fortune of Latinaires days came back around to Tortilla.

"Starting in '74, we were grossing a million a year," nods Guerrero. Memories flood.

"We went from Tejano to Latin rock," Guerrero explains. "We moved from Texas to Oakland, playing at the Orphanage in [San Francisco's] North Beach, hanging out with Tower of Power."

The Orphanage provided a surreal setting for a moment of panic in California. As Guerrero lit up a joint outside that night's venue, a stream of cops raced toward him. He stuffed the lit cigarette in his mouth and swallowed it just as the police ran past him. That's when he realized he'd stumbled into a location shot for The Streets of San Francisco.

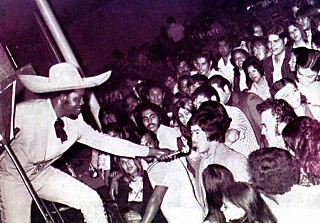

Tortilla Factory was in high-powered Latin rock company in the Bay Area. Besides Santana, Malo, War, and Tierra spicing up the West Coast, Texas had Doug Sahm's Tex-Mex outings. Under Guerrero's direction, Tortilla Factory with its wicked horn section and Texas roots was minor royalty of the peaking genre. Tortilla also had singer Bobby Butler, nicknamed "El Charro Negro," the black cowboy.

"As the Latinaires," recalls Guerrero, "we had trouble in the 1960s, checking into hotels down in McAllen. [In Tortilla Factory], we'd have to hide Bobby. We don't talk about it, but those things happened. Driving through Georgia once, we stopped in a restaurant where the sign said, 'No blacks.' There were 12 of us, and I grabbed Bobby by the arm and walked in anyway. 'Let go of me, fool!' he said. Waitress came up and says, 'Where you from?'

"'We're from West Texas!' She freaked out. She saw white boys, blacks, a bunch of Meskins, hippies, long hairs. 'What are you doing?' she said, and we said, 'Eating!'"

Guerrero tosses off the "M" word – "Meskin" – casually.

"So in the confusion, we got service. After we left, Bobby said, 'You're one damn crazy Meskin!'"

El Charro Negro

Bobby Butler doesn't remember things that way at all. From his home in San Angelo, the retired 73-year-old singer says that despite being the only black in a band of Latinos, "I never ran into any problems.

"I was the drummer for a group out of Temple before that, and they were all Latinos too," he reveals. "But I never had any racial problems or nothing like that.

"I was brought up on old-school Tejano, from the cotton fields and the barrios, in Arkansas, long before I came to Texas. I must have been 8 or 9 years old – me and Mom and my brothers out in the cotton fields picking cotton. At that time, they brought up workers from Mexico to help with the cotton harvest.

"They'd sing out in that sun all day, and I fell in love with the sound."

The presence of El Charro Negro distinguished Tortilla Factory in a way nothing else could. Butler adopted the charro hat and mariachi style of dress for the stage. His soulful croon is as authentic as the beautifully accented Spanish he taught himself. Still, the number of black Spanish-language singers fronting Tejano bands is so minuscule as to warrant unused fingers on a single hand.

"Tejano – Tejano," emphasizes Butler, "that's the music I like, and that's what I sing. That modern Tejano – that's not me. I don't really care for it. I don't knock it, but I just don't like it. I like the rancheros and the mariachis. That's my type of music.

"People expect me to sing R&B and rap, but I don't care about that. They expect me to sing that and then I start singing in Spanish. Nobody dances – they all gather round the bandstand [to listen]. Makes me feel good. The first couple numbers I do, I've got butterflies in my stomach. After that second number is like: 'Hey wow, there are some people here. These are Mexicans out here, and they're all looking at me!'"

That's what Tony Guerrero banks on as he ticks off plans for the next recording and "creating new Tortilla heads." The bandleader foresees "a minimum of four songs for Laura, four for Alfredo, and four for Bobby. Bobby refuses to do the modern Tejano. I don't blame him. He's famous for what he does. Bobby remains the one and only Charro Negro."

El Charro Negro laughs at the plans. "They better hurry. I'm not getting any younger."

Rock-a-Bye Coltrane

Back at Casa Guerrero, seated kitty-corner to his father is Alfredo Guerrero – young, good-looking, talented, and committed to not only catching the torch hefted to him by his father but carrying it forward proudly.

"My father used to put me to sleep in the crib to Coltrane," he nods. "Growing up, Tejano didn't attract me musically. I'm so used to melody, pretty chords. I didn't see myself in a Tejano direction, so I went with R&B and salsa. My father hooked me up with Art Guillermo, and I was like: 'Oh my goodness, this is it. Let's do this!'

"My father called it 'Urban Tejano.' It's like nothing out there."

Like many a modern young Texan, the younger Guerrero has a cowboy boot in hip-hop culture. He's currently collaborating with Kanye West's partner Haskel Jackson for starters. That's not his father's realm, but as a veteran musician, Tony Guerrero understands mass appeal and the importance of common languages, especially to a younger audience.

"Today, the Tejano industry is minuscule, tiny," stresses Tony Guerrero, looking across to his son, who in turn nods. "In the Sixties and Seventies, this market was huge. On Friday night we'd play to a packed house in Galveston. Saturday, Houston. Sunday, El Campo, to 2,000 people! Monday night in McAllen, Tuesday in Brownsville – five nights in a row to packed houses.

"Now, getting 1,200 on a Saturday night is a hat trick."

Tony Guerrero turns and looks to his daughter, the dark horse in the band's comeback. He has plans for her. Laura, regal and spirited in the boisterous world of Tortilla Factory, is a singer and prefers it that way.

"I don't know if I could ever get into the production part of it," she shrugs. "As far as writing songs, I haven't given myself that opportunity. What I like about Tortilla Factory is our roots are Tejano. We're never going to turn away from it."

Her background in sales and real estate came in especially handy when her father was at a loss for new musicians in the revived band. Laura's answer was Craigslist. While her father and brother still marvel at the results – a new Tortilla Factory – Laura's unfazed.

"Everything happens for a reason," she nods.

Stocking Stuffer

Stockings are hung by the chimney with care in the family room of the Guerrero house. Actually, they're crowded across the mantle, reds and greens overlapping one another, bunched in a friendly, homey hodgepodge. They're a big family, the Guerreros; no matter how many, there's always room for one more. So many celebrations take place in this room that a colorful "Happy Birthday" sign is permanently fixed.

Framed above Tony Guerrero's head is the 2009 Grammy nomination for All That Jazz.

"We were excited and flew there for it," he says. "It was hard to not win, but after a while, we knew the honor."

Alfredo Guerrero believes Tortilla's Urban Tejano is key to this year's Grammy nod.

"Stylistically, urban means hip and different, so the four songs of mine [on Cookin] have vintage Tejano horns from a chart. But it also has my R&B and my salsa singing mixed together with the Tejano. It's something completely different. The song we released as a single is blowing up like a bombshell in the Countdown USA 25 Top Tejano songs. It's number four.

"My father let me go and do big things on my own, and I didn't see myself coming back to these roots," he continues. "This last summer, when I got back the arrangements, I listened to them and I was like, 'I'm a Tejano now!'"

Those words might be the greatest gift Alfredo Antonio Guerrero ever gives his father.