The Devil in the Details

Downtown Great Streets Plan stalled by commuter roadblocks

By Mike Clark-Madison, Fri., Oct. 4, 2002

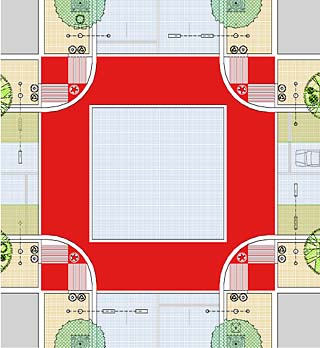

Illustration courtesy of Black & Vernooy + Kinney Associates

"A pedestrian oriented hierarchy of transportation promotes density, safety, economic viability, and sustainability. ... The safety and comfort of pedestrians is of greater concern than the convenience of a driver."

So say the city's Downtown Austin Design Guidelines, echoing more than a decade's worth of policy, planning, and promises about the Central Business District (CBD). This month, the City Council is being asked to give its okay to projects to make downtown streets more urban and ped-friendly -- even if it means inconveniencing drivers.

Are you surprised to hear that people are freaking out over this? You shouldn't be. Leave aside the usual canards about Texans and their cars and alternative transportation being "unrealistic" (file under "self-fulfilling prophecy"). If the council balks, it wouldn't be the first time Austin has failed to put its high-toned, sensible, and supposedly official goals into practice. But when City Hall told its planners to make those goals real, it may have sown the seeds of this downtown vision's own destruction.

The "near-term" package -- ready for the council since July but then postponed -- brings together pieces from several downtown initiatives. Prime among them are the Great Streets Master Plan, which details the look and feel of Austin's ideal pedestrian environment, and the Downtown Access and Mobility Plan, which uses sophisticated computer modeling to identify ways to improve traffic flow. (The package also includes bits of the Seaholm District Master Plan, the Second Street Retail District born out of the CSC/City Hall deal, and the Lance Armstrong Bikeway. See "All Tomorrow's Projects" (p.31) for the complete list.)

Now, it is a near-truism that, if you put architects (Great Streets) and engineers (D.A.M.P.) to work on the same problem, their solutions will be in conflict. And such is the case here -- particularly on the hot-button question of converting downtown streets into two-way thoroughfares. This is a bedrock principle of Great Streets, but it's strongly opposed by the driving set, with support from the Chamber of Commerce and the Real Estate Council of Austin, who cite the D.A.M.P. as evidence.

And so, after a generation of talk about a downtown where pedestrians rule and drivers are the guests, it still ain't a done deal. "There's no longer a consensus on Great Streets, now that the inevitable details are brought forward," says Council Member Will Wynn, former chair of the Downtown Austin Alliance and a longtime advocate for a more urban-and-walkable downtown. "D.A.M.P. and Great Streets were on the same track, headed in opposite directions -- right towards one another."

If We Can Walk to It -- We Will

In 1991, the American Institute of Architects sent a Regional/Urban Design Assistance Team to Austin to assess the state and fate of downtown. It told us, among other things, that the CBD has tons of potential -- which it could better realize, meeting more needs for more people, if it were a place to go to rather than through. Reincarnations of the R/UDAT have returned twice since and repeated themselves. "Many of the benefits of attracting activity and users to downtown are only fully realized if they become pedestrians," said R/UDAT team leader Tom Gougeon in 2000. If new workers, residents, or visitors "don't use downtown on foot, the potential for increased economic activity is limited."

Illustration courtesy of Black & Vernooy + Kinney Associates

Out of R/UDAT was born the Downtown Austin Alliance, which has pushed since its inception for a more pedestrian-friendly, mixed-use, big-city downtown, and for 10 years City Hall has been ever more obliging. After the Watson years -- Smart Growth, the CSC/City Hall and Intel deals, the downtown housing boom, the emergence of the Warehouse District, the Convention Center expansion, and the Downtown Design Guidelines -- God should strike dead any Austin civic leader who claimed the jury was still out on this question.

To the R/UDAT, the DAA, and the city's own planners, a booming downtown and a walkable downtown are pretty much the same thing. "If you create a great pedestrian environment downtown, you've done a lot for anything or everything that can come downtown," says Jana McCann, the city's urban design officer and point person on the Great Streets project. Rather than disproving this logic, the 1990s downtown boom may in fact confirm it -- the more walkable parts of the CBD, like Congress Avenue or the Warehouse District or the Red River strip, saw the most action. The car-heavy corridors -- Lamar, I-35, West Fifth and Sixth, Cesar Chavez, East Seventh -- basically remained the same, despite being far "busier" in the ways developers like.

In due course, downtown advocates -- foremost among them architect Sinclair Black, the "sage of downtown" and "father of the Warehouse District" -- worked out the ideas now embodied in the Great Streets Master Plan. The plan itself was produced for the city's Transportation, Planning and Sustainability Department by a team led by Black, Girard Kinney (designer of the Pfluger Bridge), and other denizens of that rarefied place where urban design and Austin politics intersect. Meanwhile, the city, at the urging of the DAA, started socking away money to pay for the reinvention of downtown's streets.

In addition to proceeds from the 1998 and 2000 transportation bonds and, in recent years, some of Capital Metro's rebated sales tax, a portion of city parking meter revenue has gone into a Great Streets fund since 1996, thanks to lobbying by the DAA. "Generally, that was conceived to help private-property owners make the improvements, because they are expensive," McCann says, citing utility relocations as a particularly big-ticket item. And Wynn notes that "the private sector, not the city, will do the lion's share of reshaping -- and yes, dare I say, improving -- our downtown." Even at that, the near-term package is priced at $17.5 million.

Two-Way Ticket

You can already see, in test-tube fashion, what a Great Street might look like, since walkability was woven into the city's Smart Growth Matrix. Projects that got incentives under the matrix -- including CSC and the Plaza Lofts -- already have the wide sidewalks, street trees, and design amenities that would mark all downtown streets, even though the Great Streets standards have yet to be officially adopted. (Different streets, depending on their function, would have different treatments -- see "The Great Streets System" (p.30) for the complete Great Streets typology.)

Though it may seem intuitive, it's actually a bit innovative for Austin to think of sidewalks, and the people on them, as integral parts of the street, rather than as extensions of the buildings on it. In the words of the GSMP, "The Great Streets typology creates a new and more equitable balance within the overall public right-of-way between the street and the sidewalk." Within the standard 80-foot downtown right-of-way, the actual Great Street would be 44 feet wide, the combined sidewalks 36 feet -- compared to the 60-20 (at best) split typical of today's downtown.

From the get-go, the Great Streets effort has presumed that most, if not all, downtown streets should be two-way. This suggestion, made in all three R/UDAT visits, has been adopted by many cities whose CBD Austin seeks to emulate, including Portland, Seattle, San Jose, Phoenix, Albuquerque, Buffalo, and Cincinnati. "We've been immersed in this issue for years," says DAA executive director Charles Betts, "and our people are enlightened and convinced that one-way streets through downtown are not best for downtown." Yet this one question continues to eclipse almost all other discussion of Great Streets or the near-term package.

Illustration courtesy of Black & Vernooy + Kinney Associates

In itself, two-way operation is not essential to a Great Street. "We can work with either a one-way or two-way street," says McCann, "and we'd absolutely feel comfortable proceeding with the design." But the GSMP presumes that streets would be converted before being rebuilt at great expense, and two-way is deemed by the pros to be essential for the new development, especially retail, that people would want and need to walk to. (Basically, two-way doubles a store's exposure to either walk-up or drive-by traffic.) City Hall has already more-or-less committed to making Second Street two-way through the retail district planned to adjoin CSC and City Hall, at the insistence of its developer/consultant Federal Realty. And again, the few existing two-way streets downtown -- like Congress, Fourth, and Red River -- are where the action is.

Few dispute that a two-way downtown street network would be slower, but no one knows exactly how much slower. "We've been fighting this holy war for six years, but nobody has any evidence either way," says the DAA's Lucy Buck. Even though the Great Streets plan announces flatly that "Congestion is a fact of life in successful urban places," downtown stakeholders were also confronting hateful CBD traffic jams. "As [Great Streets] moved forward slowly, all the other downtown advocacy actually started to work and significant projects started to emerge," says Will Wynn. "Then we started to see that Austin drivers react about as well to construction as they do to rain."

DAMPening Enthusiasm

Thus was begat the D.A.M.P., conceived to provide city staff with a computer model (the CORSIM model: a Federal Highway Administration acronym meaning "comprehensive microscopic traffic simulation"). The model could in theory forecast the effect of new projects -- be they Great Streets improvements, other roadway initiatives, or new buildings -- on downtown traffic. Consultant Butch Babineaux of Wilbur Smith and Associates (the firm that also did the recent downtown parking study) modeled a total of 71 different changes to the downtown status quo. These included various new traffic signals, left- and right-turn bays, extending or closing certain streets, allowing or prohibiting turns -- and converting downtown streets to two-way operation.

The D.A.M.P. modeling seemed to validate, or at least not to damn, two-way Great Streets; afternoon rush-hour delay (per vehicle trip) increased by less than two minutes over the 2000 baseline. For morning rush hour, the increase was less than 30 seconds. In another scenario, where Cesar Chavez remained one-way, morning delays actually decreased, and afternoon delays increased by less than a minute. (It should be noted that this modeling, done 18 months ago, presumed the existence of emerging projects like the Vignette campus -- on Cesar Chavez -- that are now defunct.)

With the D.A.M.P. modeling in hand and several other balls in the air -- Great Streets, the Seaholm plan, the Second Street retail project, and so on -- city staff was instructed by the City Council to turn its ideas into the near-term "coordinated package." The Great Streets plan had presumed phased implementation with the full Great Streets treatment first slated for Brazos, Colorado, Ninth, and Tenth, the least-traveled one-way streets in downtown.

Two other street pairs -- Trinity and San Jacinto, and Seventh and Eighth -- are also recommended for two-way conversion, with the Great Streets improvements to come later. Despite Black's strong desire to see Cesar Chavez be a grand boulevard, staff decided to leave it out, citing the "unacceptable delay" predicted in the D.A.M.P. Instead, Cesar Chavez would become half of a one-way pair with Third Street, so that Second could be a two-way retail corridor.

Everything seemed copacetic until the end of June -- when Babineaux delivered the final D.A.M.P. report and took a double-barreled shot at Great Streets. "The D.A.M.P. consultant has reviewed the objectives and proposals of the GSMP and strongly disagrees that it is necessary to convert one-way streets, especially those serving as primary corridors into downtown, to two-way streets in order to achieve those goals," he wrote in the executive summary.

The Big Wheels Object

Babineaux's off-the-reservation slam might have been dismissed as inevitable from a traffic engineer for whom "delay" is a sin that no amount of good urban design can redeem. But "we started seeing 'downtown advocates' whose barometer for advocacy," says Wynn, "measured exactly how many minutes it took to drive from West Lake Hills to their reserved parking space in a downtown garage. All this vibrancy is fine and good, but not if it slows down the commute time. They rank urban core vehicle mobility over everything else, even when it's the difference between 11 and 13 minutes."

Said citizens found their voice within the chamber and Real Estate Council of Austin, rather than the DAA, and to them Babineaux's comments -- a four-paragraph passage in a 300-page document -- were a message from heaven. Though both groups endorse the near-term package, including the Great Streets pedestrian improvements themselves, they oppose any two-way conversion except on Second through the retail district, and they cite the D.A.M.P. as evidence.

"Certainly, RECA is all about a vibrant downtown that is economically viable, and we very much support anything that is done that meets those two goals," says RECA Executive Director Janice Cartwright. "But we were just unconvinced that the conversion was necessary. The D.A.M.P. demonstrated that all the Great Streets improvements can be successfully done on one-way streets." "Speculated" would be more apt than "demonstrated," but the political die had already been cast.

The chamber's position is somewhat harsher, calling two-way conversions "experimental, expensive, and somewhat counterproductive to improving mobility" and declaring that "there is no clear balancing of interests, no established priorities, and no defined exit strategy" in case the streets need to be switched back. (To which the DAA's Betts responds, "If the changes cause problems, we'll all know it. It won't take a computer program to tell." However, the city does own the CORSIM model.)

Were it not for the chamber and RECA, the City Council might have already moved forward with the CBD package, but in the face of "controversy" and already swamped with the Stratus deal and then the budget, City Hall punted. Nothing has really changed since then, and "consensus" has certainly not re-emerged. "It's caused a lot of irrational hysteria; you'd think we were taking away somebody's child," says Jana McCann.

"We feel comfortable that it's not going to destroy anybody's life," McCann continues, but even when confronted by the D.A.M.P. data, foes "just feel it'll be a 'disaster.' They give delay as the reason they object, but they don't accept the proof of the model, and they oppose it even though we're not proposing to change the big workhorse commuter streets, and even though we'd proceed slowly and delicately. It's been a stubborn, irrational stance."

"Irrational" is a good word for what is now, pretty nakedly, a philosophical rather than practical dispute. Both sides are right -- two-way wouldn't destroy anyone's life, but it's not the only way to make streets more walkable, and Great Streets improvements will proceed regardless, and downtown can survive and probably thrive either way.

But how many times has City Hall murmured that it values people more than cars? Two-way conversion is the first thing Austin would do that proves the point -- even the Great Streets improvements, elaborate though they may be, would elevate pedestrians to equality with, but not necessarily superiority over, cars and their mobility. Both sides know this, and each is fighting not over what two-way streets do but what they represent.

So the City Council faces unpleasant reality. If it implements what it's pretended for so long was a consensus vision, it's still going to hack a bunch of people off. If it caves on the two-way question, it hacks a different bunch of people off -- and calls into question the soundness of its downtown commitment. "If we start cherry-picking" the least controversial ideas, says Will Wynn, "we defeat the whole purpose of looking at downtown from a larger perspective, and the transition to a more dense, much more vibrant downtown becomes too painful. Then everybody loses." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.