Feel the Burn

Austin author and wildland firefighter Mary Pauline Lowry takes readers inside the fire line in her novel Wildfire

By Jessi Cape, Fri., July 24, 2015

Austin native Mary Pauline Lowry has quilted a career out of interesting jobs. She's worked in construction, and with the Texas Council for Family Violence. She is a women's rights activist, and has served as a wildland firefighter on the Pike Interagency Hotshot Crew. Now she spends most of her time writing, and her first novel, Wildfire, has been optioned for film. (Naturally, Lowry wrote the screenplay, too.) We caught up with Lowry (currently living in southern California) to chat about firefighting and the parallels between her own experiences and those of Wildfire's lead character, Julie. (For more on Wildfire, see the review, p.27.)

Austin Chronicle: Your descriptions of the fire line in the book are so vivid that the reader feels like she's in the hot zone with the crew. The fire feels almost like a character itself. How did you find the balance between the characters and the work, nature, and other elements?

Mary Pauline Lowry: I definitely wanted to write about wildfire as a character and as an element in the story, because it's such a part of the story of the American West. And I feel that it's been underrepresented in fiction. The best fiction writing I've ever read about wildland firefighting is by Norman Maclean in his book A River Runs Through It and Other Stories. He fought fire in real life and worked for the Forest Service, and in one of the stories he writes a fictionalized account of his real experience fighting the great fire of 1919 in Montana. There are only like five pages about wildland firefighting, but it's so beautiful. His description of the camaraderie and the bonds between crew members was so beautifully done that I thought, "Why have I never read fiction this good about wildfire?" Wildland firefighters do like to write memoirs, and there are some good ones, but I'm a fiction lover and I wanted there to be more fiction about wildland firefighting. I wanted to share the beauty of this natural occurrence that's actually part of healthy nature, but I also wanted to talk about the people that are fighting wildfire and are doing that for a living. The people who are passionate about that – what they're like, how they act, what their day-to-day life is like, and the relationships between crew members. It's a very polarized environment. There are 20 people living together for six months of the year without much contact with anyone else, and I wanted to describe that world.

I also wanted wildland fire to be this element, this character, and for people to understand that world. I'm from Austin, and most people barely know about professional wildland firefighting. To most people, firefighting is structural firefighting. Growing up, being a firefighter meant going to the fire station and driving the red truck and all that, but wildland firefighters fight more actual fire. A lot of structural firefighters, on a daily basis, respond more to traffic incidents and medical responses, whereas wildfire is big fire all the time. Pretty fun.

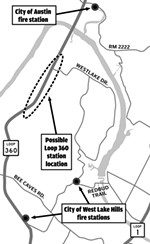

One thing that's interesting about Austin is that now there are what we'd call urban interface areas – urban communities in densely forested areas. Think West Lake. Parts of Austin are at increased risk of wildfire because the temperatures have been heating up in recent decades as a result of climate change. More and more of Central Texas is at risk of fire, so I think it's something that might become more of an issue.

AC: That makes me think of the Bastrop fire in 2011.

MPL: That was something I never experienced in Central Texas in my whole life. If you look at a map of wildfire progression in the last 50 years or so, it's spreading to areas where we didn't formerly suffer this problem. When you look at Bastrop, it was so beautiful, but you'd see these houses in such a nice forested area and you'd think, "What a great place to have a house." You don't immediately think those forests could burn someday. I think people in Central Texas have more of an awareness now.

AC: How much of the story is autobiographical and how did you decide to write from Julie's perspective?

MPL: Well, first off, I was not the only woman on the crew. My first year, there were three women on the crew, and my second year there were two – me and another woman. So right away you can see there are fictionalized elements. I used my experience as a woman who fought fire as a Hotshot as sort of a research jumping-off point. The research had already been done; I'd already fought wildfire. I didn't want to write a memoir. I love fiction, and I wanted to write it using my experience. I used the characters that I knew, my understanding of the culture and that world and the actual work, to write a story that was fictional.

AC: The story has subtle social commentary running through it. You talk about things like the intersection of women and sex and body image, and sexism in the workplace.

MPL: There are a couple different issues. The most obvious one you're talking about is gender and being a woman working in a very masculine world. The limitation of women in certain work fields is so pervasive through many different levels of our culture, and I feel like the world of fire is a great metaphor. Many jobs on different socioeconomic levels, that require different levels of education, are so limited for women, and women are the minority in so many fields to this day. If you go to hospitals, the vast majority of nurses are women. I worked at the National Domestic Violence Hotline, and the majority doing that were women. But there are so many fields where the number of women doing the work is very limited, and it's not just in these obviously masculine, "macho" fields. It's not just in construction work or firefighting. A very small percentage of pilots are female. I like to talk about film because I do screenwriting, too. Only 4 percent of directors in major motion pictures are women – and that's getting close to the number of women that are Hotshots. Only 10 percent of screenwriters of major motion pictures are women. I think with fighting fire, people say, "Women can't hack it," or "Women aren't strong enough," which is not true, but then you see these other fields and it's really not true.

AC: A few years ago, I spoke with professional welder Inez Escamilla about using her smaller size – something her male co-workers gave her flak for – to her benefit. She boosted her career by recognizing her strengths. Have you experienced anything similar?

MPL: That is awesome! Women do bring certain skills. I do want to say that one difference between my experience as a Hotshot and the experience of my fictional character, Julie, is from the top down on my crew, female firefighting was embraced and it was welcomed. That said, I was in an idyllic, best-case scenario, and every day I still had men telling me, "We don't think women should fight fire. We like you, but you're the exception that proves the rule that women shouldn't fight fire." It was a really confusing situation. These guys were my best friends, and they are still close friends. They love me, love having me around, and they could see my work, that I could do it, but they [still] said that women shouldn't do the work. It was crazy no matter what.

And that was best-case scenario where I was embraced, accepted, and loved, and I was still getting that kind of flak. But I have other friends on crews, where, from the top down, the message was very clear that they had been forced to hire women. Those situations were much, much worse. Even recently – I think it was in 2014 – 10 female firefighters filed a lawsuit because they were being sexually harassed and one had been assaulted by her boss. There's this really extreme end, and I was on the happy end, so I'm trying to illustrate someone who was in the middle. Someone who was doing a good job, kicking ass at her work, but also going up against the sexism that's pretty pervasive in the fire world. I wanted to convey that ultimately Julie did find a place of belonging there. I was also trying to strike that balance with the male characters, show why each one was lovable and why each one belonged, and that they ultimately did accept her.