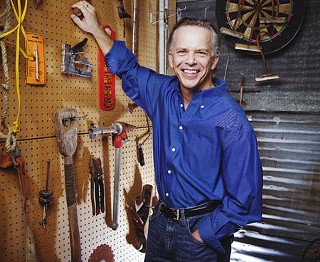

Working Playwright

Steven Dietz just wants to get in, roll up his sleeves, and make the words better

By Robert Faires, Fri., Nov. 7, 2008

Some mornings, just before he dashes off to the University of Texas campus to teach a playwriting class, Steven Dietz will get on Google, type in his name and the title of one of his 30 plays, and find as nasty a review as he can – you know, one that's downright toxic and really excoriates his script, that flays the dramaturgical hide off his literary creation – then he'll print it out, bring it in, and share with his students every bit of abusive invective down to the last lacerating adjective.

Now, he does this not to lord it over the reviewer, dissecting and dismissing his critic's ignorant cavils with the sneering superiority of the creator. Nor is it the self-flagellating impulse of a theatrical masochist. Rather, it's Dietz's way of showing his charges one of the hazards of their chosen occupation: Invariably, someone won't like your play – indeed, may hate it and express that loathing in the most demeaning terms – and that's something you as a playwright need to deal with. It goes with the territory; it's part of the job.

You read that right: job. Some playwrights may consider themselves mystics, channels to some holy writ of drama that they transcribe and deliver to theatregoing masses hungry for the word, but not Dietz. He comes at it from more of a blue-collar perspective, as work – and not work in the sense of a chore, of the soul-numbing 9-to-5 that you endure to pay the bills, but work as honest labor, a trade in which you take pride and from which you derive a sense of accomplishment, of service.

"He talks about going to work as a playwright the way anybody goes to a regular job, and that is a very refreshing ethos," says Suzan Zeder, head of the playwriting program at the UT Department of Theatre & Dance. "So it's not in all these esoteric terms. And it's not a devaluing of the art. It's getting art in the right category: It's a thing we make with our hands, and we do it together."

Zeder is part of the reason Dietz is in Austin now. A few years ago, the Department of Theatre & Dance and the Department of Radio-Television-Film teamed to hire a writer to teach both playwriting and screenwriting. It was, Department of Theatre & Dance Chair Robert Schmidt says, "a reflection of our understanding of the realities of the businesses, which are less and less disconnected from each other these days." The departments wanted this writer to be a major player, and they had the financial backing of the university to secure one. Zeder calls it "an opportunity that comes along once in an academic career. I knew we had to not screw this up."

Dietz fit the profile of their major player. His output is prodigious, some 30 plays in 25 years, and at a point when other playwrights might be winding down, he still steadily generates a couple of plays a year. He seems able to write in almost any style, from ensemble comedy (Becky's New Car, his newest work) to topical docudrama (God's Country) to literary adaptations that run the gamut from Goethe (Force of Nature) to Go, Dog. Go! (adapted from the P.D. Eastman preschool classic with his wife, playwright Allison Gregory). His plays are regularly lauded with honors: the Kennedy Center Fund for New American Plays Award for Still Life With Iris and Fiction; the PEN USA West Award in Drama for Lonely Planet; the Yomuiri Shimbun Award – call it the Japanese Tony – for his adaptation of Shusaku Endo's novel Silence; the Edgar Award for Drama from the Mystery Writers of America for Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure, adapted from Arthur Conan Doyle's stories and William Gillette's play; a Pulitzer Prize nomination for Last of the Boys. And he is not only acclaimed but is, as Schmidt notes, "as produced as any other living playwright, which is pretty astonishing." And the fact that he is still so busy, being commissioned by and working with such leading institutions as Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago, McCarter Theatre in Princeton, A Contemporary Theatre in Seattle, and Denver Center Theatre Company in Dietz's old hometown, just added to his luster. Here was a writer who was still active in the field, who could bring his current professional experiences into the classroom.

You don't build up that kind of curriculum vitae and enjoy that kind of demand without being able to deliver the goods reliably and consistently, in short, to do the work. It's a quality that leaves his peers thunderstruck, even the one who lives with him. "First of all, the guy is a freak," insists Gregory. "Total freak. He writes, like, two plays a year. Every year. Only I think this year he wrote three. That is in addition to the teaching and the workshops and speaking and directing and extensive traveling and the parenting he does. He writes as if it were his job, whether or not he feels like it. He doesn't wait for inspiration – he told me once that if he waited for inspiration, he'd never write a damn thing. He decides he's going to write a play about something, and then he does it. It's weird. I believe that's called discipline."

Zeder, who has 35 years as an award-winning playwright to her credit and is on leave this fall to work on her 16th play, says: "Now that I've been back to being a full-time writer, I absolutely am in awe that Steven is able to keep the kind of professional career that he's had going with the load that he carries at UT. I don't know how he does it. He's in production around the country and is very thoughtful about getting to those rehearsals, but it's never at the expense of his colleagues or his students here. He's got to be three people."

This industrious dramatist will tell you how he came by this work ethic. His father was a Colorado railroad man whose job required him to be on 24-hour call, who might have to plow through a Rocky Mountain blizzard to get to a train. "I grew up with the notion that work is necessary," Dietz says. "Work is a celebrated thing in my family and my upbringing. My parents' mantra essentially was: Be useful." That principle is so deeply embedded in his bones that he considers the word "workmanlike" – a term many a playwright would bristle at – an honor. "I'm much more comfortable with the phrase 'working playwright' than 'professional playwright.'"

Wendy Bable, a grad student in the M.F.A. Drama and Theatre for Youth program who's directing the production of Dietz's Still Life With Iris currently running at UT, feels a kinship with the playwright: "I know that his dad worked on the railroad. My family are all steel-mill workers from Pennsylvania. I'm the first person in my family to go to college, so both of us have very working-class, blue-collar backgrounds. I've talked with him a bit about it, and it's not magic; it's work. There are days when you're not going to feel inspired, and you go and get the work done anyway. You stay at your craft until the work is done."

Craft. You don't talk about Dietz for long without that word coming up. "I have always admired his plays because I think they're some of the most solidly crafted plays [I know]," says Zeder. "There's nothing trendy about Steven's work. It's there for the long term. It's like going into a really beautiful furniture store and seeing hand-done craftsmanship in the way his plays are put together."

"Steven is a craftsman," echoes Gregory. "And just like in the days of old, he takes great pride and deep pleasure in the fact that theatre is made by hand. Playwriting is about as anachronistic as it gets, and that's just fine with him."

But to hear it from this old-school artisan of the drama himself – who, by the by, never saw a play until he was in high school, never went to grad school, never took a playwriting class – this attitude was something he picked up from other playwrights before he set pen to paper. At the Playwrights' Center in Minneapolis, he was able to work as a director with writers such as Lee Blessing and August Wilson as they were developing new scripts. "I was watching these writers just do their work," he recalls. "And I assumed that's what a playwright did: got in, rolled up his or her sleeves, and made the words better. Made the story better. It wasn't until later that I realized, no, a lot of playwrights don't do that. A lot of playwrights are arm-folders. They walk into the room, and they fold their arms, and they don't want to collaborate."

Such self-importance doesn't stand with Dietz. "A lot of people dine out on the idea that what they're doing is so special and so difficult," he says. "That stuff makes me sick. I try not to tolerate it in my students, and I absolutely will not tolerate it in myself, nor would my friends let me get away with that. I was lucky enough in my formative playwriting years to have [the romantic notion of playwriting] kicked out from under me and instead to embrace working hard at the part you can control – where the short word goes in the sentence, where you come into the scene – and have patience, tolerance, and forbearance with the stuff you don't control." Like who does his plays. Like those vituperative reviews.

"I grew up playing sports, so I lost regularly," he adds. "Perfect training for being a writer. You wrote today, wasn't very good. Come out and play tomorrow."

He plays – by which, of course, he means works – at every opportunity: "Spending time with my family, my friends, is crucial to me, but that two hours that I can work ... I spend most of my time constructing an opportunity to work." And the points of the process when he works hardest are his favorites. Hearing a play for the first time, he says, gives him "stuff to solve." "I love that. The first reading and first week of rehearsals test the play, and they test me: What do I need to do?"

Dietz considers it the writer's responsibility to answer that question, for the sake of his fellow artists: "If there's something wrong with my play, no matter how it's produced, there's something wrong with my play. The exceptional collaborations that have added to my plays are allowed to happen because I've done job one. I've laid out a text. That's only a percentage of the theatrical event, but you don't get to do less work [because of that]. Someone else doesn't get to run the last 20 meters of the race for you. You have to finish your work so the designers can finish their work. When I was a young playwright, I kept thinking I was done. I'd finish the play, and I'd think I was done. Or get the play staged and think I was done. Now I never think I'm done. And my plays have improved because of that."

He's back to craft, and now that he's in the classroom, he is responsible for instilling its importance in young playwrights. Fortunately for him, they seem eager to learn just that. "Nearly every student that I've interviewed says: 'I want to learn structure. I want to learn nuts and bolts.' So that's what I teach," he says. "I'm trying to fill up a toolbox for them, and my job is to give them more tools than they need. You're going to write that first rock & roll song with those three chords that you know, but eventually you're going to need a diminished seventh, and your craft is going to have to grow with your ideas. As I tell them, my job is to make myself unnecessary. I was not a good teacher of acting when I was younger, because I would make myself so necessary to my students. If I was there, they were really, really good, and if I wasn't there, they'd be really bad. It's so seductive to make yourself necessary to your students. I want to be there for my students, but ultimately [I want] them to say, 'This is mine now, and I don't need that Dietz to tell me where to put the short word in the sentence.'"

Dietz is also intent on showing his students as much of the career they'll be pursuing as he can. "I feel like when my position was created here, it was created to put a professional playwright and the good, bad, and ugly of what goes on in one's career on the faculty. My students are on deadline for something that they have to write for me, and I'm on deadline for a play for the Guthrie Theater, and we have the same 26 letters, and we're struggling with them every day. On the days when you don't have any ideas, you still have to write that play. And when the actors are staring at you, and it's Tuesday, and they're waiting for you to fix that scene, it's a deadline art form."

And he wants the students to see him handle that deadline firsthand. Whenever he's off to a rehearsal for one of his shows, no matter what city it's in, he brings one of his students with him. "It's watching me cut, watching me change, and in some way really demystifying the process," he says. "It's people in a room. Dietz is trying to make his play better."

Zeder sees Dietz connecting as a teacher: "He shares his own battle scars, but he doesn't teach from an anecdotage. There's no distance between him and the students. He's very frank with them. He's very, very tough on them but always from a positive and productive base."

She also sees him taking the lead in a movement within the department to deepen the level of interaction among the major programs, to treat, in her words, "collaboration as not something that just happens in production but something that happens in the generation of work from all the artists that are involved. Steven has been at the forefront of it." He proved that with The Last Hour, an outgrowth of a playwriting seminar he taught last year. Sessions lasted three hours, but he opened up the last hour to all of the new actors, designers, and directors in the department, "and they just made work together," says Zeder. "It really was blazing a new trail."

Schmidt concurs. It's helped foster "a sense of genuine and productive collaboration – and not just among the faculty but among the students – that I haven't seen in a long time. And that I think you don't see in a lot of schools. Or in a lot of theatres, for that matter."

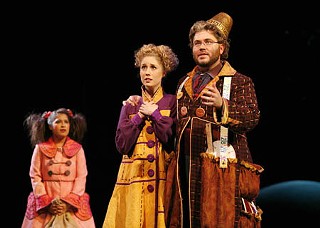

For his first two years here, Dietz pretty much limited his activities to the Winship Drama Building. But that began to change last spring when he ventured beyond the 40 Acres to direct John Patrick Shanley's Pulitzer Prize-winning Doubt: A Parable for Zach Theatre. (The show was a sold-out hit and won the B. Iden Payne Award for Outstanding Production of a Drama.) This season, Dietz will return to Zach to stage the premiere of his new romantic comedy Shooting Star. (Full disclosure: Chronicle contributor Barbara Chisholm, who is married to this writer, is cast in that production.) And local audiences are getting more opportunities to experience this craftsman's stories; this week, two plays of his are in production: The Nina Variations, his riff on Chekhov's The Seagull, as mounted by Gobotrick Theatre Company; and Still Life With Iris, his award-winning 1997 play for young audiences that's being given an enchanting production at UT. It's encouraging to see that Dietz is becoming more deeply woven into Austin's cultural life.

Maybe the hardest thing about Dietz's move here was leaving Seattle, his home for more than a decade and a place where he and his wife had deep personal and professional roots. Zeder reports that on a recent trip there, she ran into actors, playwrights, and directors who kept asking her: "How's Steven doing? How's Steven doing?" "And in a way they were so disappointed to hear that things were going so well because they really want him back."

Just to be clear, those folks don't want Dietz back because he writes well-crafted plays. They miss the guy who isn't on the star trip, who isn't folding his arms, who isn't telling you how difficult it is to be a playwright. They miss the guy who rolls up his sleeves, who does the work, and who keeps smiling as he does. "I was so impressed with his personal generosity as well as his accomplishments as a playwright," says Robert Schmidt. "He's a great playwright but a really nice guy."

"He's very centered," adds Wendy Bable. "He's very matter of fact about his work. He's neither too humble nor too arrogant. He's very straightforward. I think he is who he is and he does what he does."

That, explains Dietz's partner in art and life, Allison Gregory, is because "Steven is so well-built as an artist, so beautifully put-together as a human being. He is nearly perfectly balanced between left and right brain, between intellect and invention, head and heart, and that balance manifests itself brilliantly in his work and in the way he works his life."

Cue the final word from another working playwright, Kirk Lynn of the Rude Mechs: "It's not that Steven Dietz is a fine swordsman in addition to being a great writer or that he can handle a Cessna with the same agility that he directs a play. What makes Steven Dietz well-rounded is that he's a challenging artist of the first degree and a totally normal man who can listen to Bob Dylan and talk baseball. I wouldn't be surprised if he liked to drink Budweiser and lose money playing poker. Meeting someone like Steven who can sit alone in a room and wrestle with the universe before being on time to take his kids to the Spaghetti Warehouse gives me great hope. It gives me a road map to 90 percent of what I think I want in this world. It makes Steven Dietz something more than just a successful writer and director living in our community. It makes him a role model."

Still Life With Iris runs through Nov. 9, Thursday-Friday, 8pm; Sunday, 2pm, at the B. Iden Payne Theatre, 23rd & San Jacinto, on the UT campus. For more information, call 477-6060 or visit www.utpac.org.

The Nina Variations runs Nov. 6-23, Thursday-Saturday, 8pm, at the Dougherty Arts Center, 1110 Barton Springs Rd. For more information, call 708-1893 or visit www.gobotrick.org.