The Art of the Business of Art

Gallery owners David Berman, Steve Clark, and Wally Workman on promoting artists and selling art

By Sam Martin, Fri., July 30, 2004

Visual artists of all ilk have a thing with money. Most don't have enough of it, at least not enough to live on while they produce their art. And many more don't know how to get it, short of working a day job that comes nowhere close to holding their hearts like the sound of a paintbrush as it dances across a canvas or the satisfying slice of a knife making its way through a fresh hunk of clay. In short, most artists go blank, get nervous, or give up when it comes to dealing with filthy lucre.

Luckily for them (or at least those who manage to get representation), there are galleries and gallery owners. Like a musician's manager or writer's agent, a gallery owner can make the difference for an artist who is selling work and one who isn't. These men and women are promoters and facilitators, but most of all they are businesspeople. If it's the artist's job to make good art, it's the gallery owner's job to sell it.

Interestingly, many artists are not only baffled by how to make money with art, but they tend to look distrustfully at those who would profit from their creative energy. (Most galleries take at least a 30% cut of sales, and some take as much as 50%.) But as any "successful" artists will tell you, having work in a gallery is beneficial, meaning higher prices for the work, the possibility for added exposure in other cities, and someone actively selling one's work on a daily basis. Most importantly, though, is the fact that by having their work in a gallery, artists can leave the business side to someone else and focus on creating.

Aside from what galleries can do for artists is the question of what they can do for the Austin arts scene. Even though the owners profiled in this article are all businesspeople first and art lovers second, each has a real commitment to art, artists, and how they affect Austin. It goes without saying that all gallery owners want to see the visual arts scene here get more attention and draw in more admirers/customers. But no one says they chose to spend their lives around art because they wanted to make money (cue laughter). It's because they have a deep appreciation for how art can enrich, excite, and educate individuals and the city as a whole.

These people welcome anyone and everyone into their galleries, whether or not the reason they're there is to buy art. That's because they're aware of the synergistic character of the Austin art scene (what Austin Museum of Art Executive Director Dana Friis-Hansen calls "art ecosystems"): It's not one museum or one artist that's going to make this town a visual art destination on par with Santa Fe; it's the fact that we're all in this together. As a result, many local galleries and museums pay dues to be part of a collective called In the Galleries Austin, which prints a brochure and hosts a Web site to spread the word about current art shows and pitch Austin as a place to come experience art.

The spaces covered in this article are all established galleries showing primarily midcareer artists, but the scene is also home to a strong contingent of alternative spaces for artists just starting out. Those will be covered in a future installment of this ongoing series on the personalities behind Austin's visual arts scene. (For the first installment, see "Talking Art at the Top," July 2.) For now, David Berman of D Berman Gallery, Wally Workman of the Wally Workman Gallery, and Steve Clark of the Stephen L. Clark Gallery have a lot to say about artists, the business of art, and art in Austin.

The Philanthropist

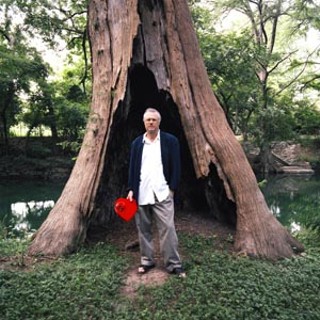

To know David Berman, you have to know that he lives on about 100 acres near Wimberley in a beautiful limestone house surrounded by porches. It's a short golf-cart ride down to a dammed creek where the swimming is heavenly and about 50 minutes by car to 1701 Guadalupe, where you'll find his art gallery, D Berman. For the 50-something Berman, who spent 25 years owning and operating a film business in Houston, the Hill Country is something of a paradise. Owning an art gallery (and working there four days a week) is pure gravy.

Berman has a slight build, gray hair, and a mild-mannered presence that is offset by the striking opaque yellow round glasses he wears. Although his voice is soft, he speaks with confidence, and when you get around him you can almost feel the success that has followed him all his life. While he's a relative newcomer to the art world – his gallery opened in 2000 – he is entirely engaged in and excited by what's happening to the visual arts in Austin, even more so than some longtime gallery owners around town. That could be because he's the new kid on the block, but it could be that he brings a fresh perspective to the city and its art.

Born and raised in Brooklyn, Berman moved to Houston at age 18 when his father changed jobs. After a year at Lamar High School, he came to UT to study film. That's where he met his wife, Ellen Berman, a painter known for her oil still lifes. (Ellen was represented locally by LyonsMatrix Gallery until its closing in 1999.) The two married in 1968 and after college moved to New York for a year before returning to Austin to try to eke out a career in the film business. When that went nowhere, Berman took a job at the NBC affiliate in Houston. Five years later, he opened his own film company, which he ran until retiring in the early Nineties.

After moving to Wimberley in 1998, Berman still had a lot of energy to do something, though he wasn't sure what. In Houston he'd been an infrequent art collector but had always been aware of the Austin art scene because of Ellen's involvement here. He also thought that the art scene in Austin could be improved. "I felt that Austin didn't have a lot of good quality galleries, at least the kind of galleries I was used to growing up in New York and living in Houston," he says.

So when he learned that Camille Lyons was set to close LyonsMatrix, he went and looked at her space to see if it would interest him. It didn't, but on a walk around the neighborhood he ran across Galeria Sin Fronteras, a showplace for contemporary Latin American art run by UT professor Gil Cardenas, currently a provost at Notre Dame. The natural light, tall ceilings, and open space of the corner gallery appealed to Berman, so he asked Cardenas if he was interested in leasing the space. He was. "Within a few months, all of the sudden I was doing this," says Berman.

Now, D Berman Gallery shows contemporary regional art by artists living in Texas. In the four years it's been open, the gallery has won two awards from the Austin Critics Table, one for best group show and one for a solo installation by internationally renowned artist and local treasure Michael Ray Charles. Berman just had his most successful month ever, largely because of the incredible response to Lance Letscher, whom he represents and whose work he showed concurrently with Letscher's AMOA exhibit "Books and Parts of Books."

Still, the business of running a gallery hasn't been necessarily profitable. Berman realizes that the art scene here still has a long way to go before galleries like his can make it year after year and before artists are able to make a living without having to move away. "At the beginning of this year, I wasn't sure we were going to be able to operate past our five-year plan," he says. "If I were to add up the profits and losses over the four years I've been open, I would see that I've spent far more than I've taken in. But after last month, I have hope. Plus, there's no doubt we have a great community here. The MFA program at UT provides great energy. Dana Friis-Hansen at AMOA is a great advocate, and with the growth of the Blanton, things are only going to keep growing."

This optimism has led Berman and his wife to start a foundation to support the arts. So far they have given money to AMOA and have put together an advisory committee to look into future projects that might give grants to individual artists. "I think our artists deserve to be compensated for what they do, and I think it's a sad commentary that so few of our artists are able to support themselves on their art," says Berman. "For me, art can personalize and enrich an environment. You establish a relationship with something in a gallery, and then you take it home and it becomes a part of your life." Plus, says Berman, the visual arts are good for Austin. "There's a million reasons why a vibrant art scene is important to a city, and the visual arts is an area that I think Austin has been negligent in taking advantage of," he says. "Art attracts business, and it makes the city a more interesting place to live. We're not going to be Houston. We're not going to have a Menil Collection or a de Menil family or the Nashers in Dallas or the Basses in Fort Worth. But Austin has an opportunity to be a center for art."

Until then, Berman will continue his commute from his patch of paradise among the oak trees and the hills.

The Soccer Mom

The way she tells it, Wally Workman's adult life as a single mother trying to support two kids while running an art gallery hasn't been that tough. After her two sons were born, Workman would bring them into the gallery to sit among the prints and oil paintings while answering phones and talking to designers and other customers. As infants they probably made a little noise, and as toddlers they most likely got into a few things. But owning a gallery was what Workman wanted to do, so that's where you'd find her and her kids. Now that the boys are 13 and 16 years old, she has a bit more time to commit to selling art but not much. As it's always been, being around art is a labor of love for this gallery owner.

Born in Europe in the 1950s, Workman moved to Arlington, Texas, when she was a year old. As a child she would go to the museums in Fort Worth and stare at the new art being created by an increasingly experimental international art scene. She remembers being inspired by color-field painter and Bauhaus artist Joseph Albers, and after the show she and her brothers and sisters ran home to paint large colorful squares in the family garage.

As a student at UT, Workman studied art history, and not long after graduation she began helping a friend run his art gallery on Anderson Lane. Early on it was apparent to Workman that he didn't know what he was doing, and he soon lost interest, selling the gallery to Workman in 1980. Three months later she moved the Wally Workman Gallery to its present location at 1202 W. Sixth.

In the beginning, Workman sold mostly prints and serigraphs, but soon she started to take interest in local painters. Now, original art is all she deals with – most of it paintings. Most important to Workman, though, is that her artists are still all based in Austin. "Of all the galleries in town, with the exception of Bill Davis', we're the only one that shows mostly Austin-based artists," she says.

Like all good galleries, Workman has cultivated a particular aesthetic for her space that can be best described as impressionistic. One of her artists is watercolorist Gordon Fowler, husband to singer Marcia Ball. His superb depictions of stone houses and landscapes from the French countryside could easily pass for light studies from the 1890s. Another is Will Klemm, a popular artist who uses pastels to create moody natural scenes with long shadows and sunlit breaks in dark clouds. For Workman, representing Klemm, who was unknown before Workman began hanging his art and who now regularly sells out shows in New York, has been one of her proudest achievements.

"I love working with artists from the beginning of their careers," she says. "You start by showing someone's work and touting them, and they start to sell their work, and sometimes they sell so much, they can start to do their art full time. It certainly doesn't happen overnight, and sometimes it takes years of both the gallery and the artist working to make a career. This job is very cumulative."

According to Workman, the same can be said for the arts in Austin as a whole. Having watched the scene from her end of Sixth Street for almost 25 years, she says things have improved, but there's still room to grow. She also thinks that the galleries here can play an important role. "Getting people to come to the galleries is part of the whole process of growing the arts scene in Austin," she says. "If they can't get out and look, then they won't get the appreciation or the desire to start collecting."

And for Workman, that is also what's going to help get her two boys off to college.

The Art Preacher

When you walk into the Stephen L. Clark photography gallery on West Sixth, a sneaker's throw from both Waterloo Records and the gnarled-but-not-dead-yet Treaty Oak, the first thing you see is Clark himself seated behind a laptop computer at his large rustic wooden desk. Even before any words are exchanged, you'll notice his car salesman's smile and his insistent eyes staring at you through round wire-rimmed glasses.

If a gallery's purpose is to sell art, then Steve Clark has found his calling. The 57-year-old native Texan grew up in Houston and went to Southwestern University in the mid-Sixties before opening his first successful business – the original Waterloo Ice House – in 1976. There he booked bands, sold food, and even hung local artists' art on the walls. After selling the restaurant in 1991, he started looking around for something to do. Having always been a photographer himself, he figured he'd try shooting CD covers and rock shows, until a photographer friend asked Clark if he'd try to sell his work. He agreed but not before going to see another friend, screenwriter and photographer Bill Wittliff, to ask for advice. "Bill said, 'Not only is this the right thing to do, but you're the right person to do it,'" Clark says. "Then he asked me if I wanted to sell his Lonesome Dove stills." The photographs, which Wittliff shot while the television movie was being filmed, were part of Clark's collection when he opened the doors of the gallery in 1996, and they are still his best sellers.

In short, Clark has a knack for knowing a good thing when he sees it, whether that's a need for a restaurant in town or an art gallery selling quality photography. He's direct, enthusiastic, and a born salesman. He believes in art and thinks you should, too. "I preach art because I think it's important to live with a constant influx of it," he says. "Every day I wake up at 6am, and the first thing I do is listen to music. What I do here is help people surround themselves with things that are meaningful."

Clark is also aware of his gallery's role in the larger art community in Austin, but he is careful to point out the difference between what he's doing and what a museum does. "For one thing, the art at a museum is not for sale," he says. "What I do here is put good art on the walls and then sell it. Most people can afford to buy something from me, even if it's just a book." And for those that just want to come in and have a look? "I encourage them to come in, sit at the table, read my photography books, and just learn."

This enthusiasm for the business side of art shouldn't cloud Clark's awareness that for the arts to flourish here on any level, our artists need incentive to stay and keep working. "I am very much about artists getting to the next level and making a living off their art," he explains. "But to do that, we have to pay them. Otherwise, they can't pay their rent, they can't do their art, and there is no art scene."

One of the artists Clark has watched grow from an unknown to a full-time and widely collected photographer is Kate Breakey, who started her career in Austin and now lives in Tucson. Her large black-and-white hand-painted photographs are always hanging somewhere in the Stephen L. Clark Gallery, though if they're not, Clark will gladly pull out any you might want to see after thumbing through her latest book. "The first time I saw Kate's work, my jaw dropped," he says, getting up from his chair, hands and arms waving like a tent-revival preacher. "And I said, 'Kate, every day a photographer comes into my gallery and says, "I want you to represent my work," and I say, "Your work is competent, but I don't have a market for it."' But Kate's work was different. I saw someone whose work was fully realized and was in a league all its own. I knew instantaneously which clients of mine would buy which pieces, and I told her right then and there."

Breakey's photography is a perfect example of the character of the work Clark sells in his gallery. He calls it "lyrical and literate," and indeed the black-and-white images are a little of both, with Breakey's close-ups of birds, Jack Spencer's frozen landscapes, and Wittliff's rustic Old West scattered about the place. Clark, who likes to spend time canoeing or sailing, is fond of saying that everything you want to know about his artists is depicted in their art. It's also true that the artists you see on his walls are a reflection of who he is. Here is a man who, like his artists, is lyrical, literate, and very professional. He's also going to keep on preaching the good word on art in Austin. ![]()