Orson Welles Refracts Noir in The Lady From Shanghai

It's the maverick director versus the world at AFS Cinema

By Julian DeBerry, Fri., June 28, 2019

Orson Welles never made a Hollywood film without Charles Foster Kane that landed successfully on its feet. Every studio project beyond his renowned debut is fixed with an asterisk, a push and pull between domineering artist and rigid external parties, with some excuse for its lopsided happy ending or enormously bloated budget. Yet these hindrances that would otherwise beset other directors were sometimes creative magnifiers for Welles.

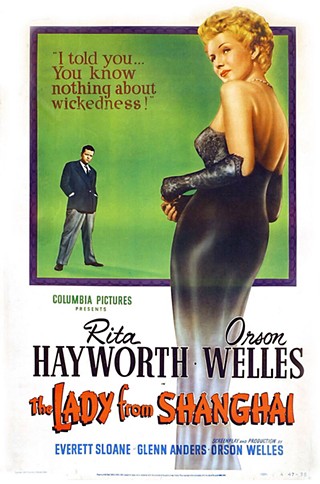

Case in point: The Lady From Shanghai, the director/writer/actor's 1947 adaptation of Raymond Sherwood King's If I Die Before I Wake and the latest entry in Austin Film Society's Noir Canon. Noir was seen as a formula that studios could adapt and pump out quickly, and so the idea of Welles, desiring to push and tinker with the medium with each outing, tackling the form makes creative differences seemingly inevitable.

This simple tale of Irish sailor Michael O'Hara (Welles, voicing the flimsiest of accents) being roped into a boat ride from New York City to San Francisco by the seemingly innocent Elsa Bannister (Rita Hayworth, Welles' estranged and soon to be ex-wife) and her husband Arthur (Everett Sloane) is an easy one to grasp. But Welles' refusal to adhere to these guidelines predictably resulted in a production plagued with reshoots and forceful edits, resulting in a cut more to the liking of Columbia Pictures President Harry Cohn than the zealous director.

The off-set friction can be felt with every abrupt transition and jarring cut, yet even in its mangled state the film still endures because of Welles' challenging voice seeping through. He is more interested in how the pieces within noir's conventions are put together than the pieces themselves. Wryly delivering familiar traits and icons from this mold, the filmmaker allows an absurdity for the material that transcends its counterparts. O'Hara and Bannister's first meeting is incited by a repeated close-up of a cigarette, conveyed by Welles with such comical, heightened emotion that it spurs a mass of callous bodies to charge the frame with hysterical violence. Bloodshed later takes hold of the plot when a character cheekily pleads for O'Hara to murder him for a handsome sum of money, as if he's privy to the machination of this world and acting as an explicit conduit between the viewer and the film itself.

This tonal escalation would rub any 1940s studio head the wrong way, and it is brought to a literal breaking point in the film's greatest set-piece: the Crazy House. Bodies are twisted out of proportion, perception is skewed, and our principal figures play target practice in a hall of mirrors while their image multiplies throughout the frame. As bullets shatter the surroundings and bodies collapse on the floor, the lens itself cracks. A blunt signifier that, for Welles, content and form are interlaced. The resolution to a story that's embedded within a recognizable pattern is also a resolution to what's stitching the story together. No matter how distant the final cut was from Welles' intention, the notion of him having fun always remained.

Austin Film Society’s Noir Canon presents The Lady From Shanghai @AFS Cinema Fri., June 28, 7pm; Sun., June 30, 4pm; and Wed., July 3, 7pm. Tickets and info at www.austinfilm.org.