How Costume Designer Edith Head Changed the Look of Hollywood

AFS Cinema spotlights films featuring the Oscar-winner's designs

By Jill Morena, Fri., Jan. 11, 2019

When I was about 9 years old, I received a large picture book of old Hollywood film stills as a Christmas gift. I remember it was impossibly dense with photographs of stars in wondrous clothes from the 1910s to the 1970s, butting up against each other, jostling for the most sublime single image on the page. I spent hours and hours with that book until the pages began to fall away from the spine and spill out onto the floor whenever I opened it. These static images, frozen outside of narrative and time, represented for me an escape hatch into glamour and mystery, and a world of women with a confidence and intensity that I longed to experience within myself. I remember Marlene Dietrich, her face framed by a bewitching circle of iridescent black feathers, and Clara Bow, grinning conspiratorially in satin cloches with matching bejeweled shoes. I was unaware that I was marveling at the effort of a woman who worked determinedly behind the scenes to dress such early Hollywood luminaries.

Edith Head began her long and extraordinary career in the 1920s, mainly under the tutelage and shadow of one of the great Hollywood costume designers, Travis Banton. When she was hired at Paramount, she had zero experience designing clothes and an uneasy proficiency in drawing the human figure. Head later claimed that she never considered herself a design genius, but she used her instincts, industry savvy, deft efficiency, and the delicate arts of compromise and diplomacy to become the most successful and prolific costume designer in Hollywood history.

One of the joys of costume lies in its transformative powers. Head was one of the great arbiters of female character transformations onscreen, changing awkward women in ill-fitting clothes into individuals confident with a new carriage and awareness, like Olivia de Havilland in The Heiress (1949); or reverse-engineering those in extraordinary circumstances who longed to be ordinary, like Audrey Hepburn's princess in Roman Holiday (1953).

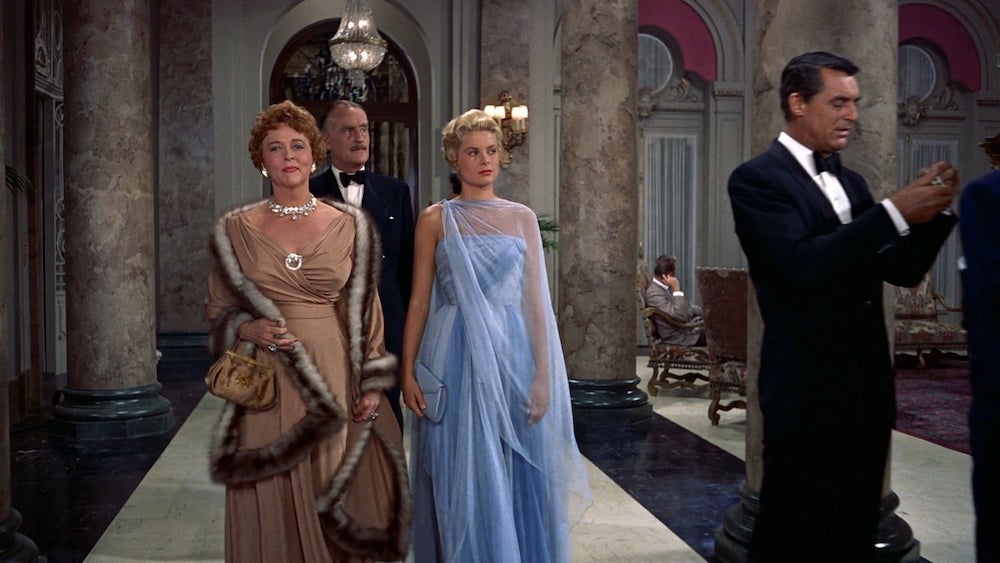

Many of Head's triumphs occurred during the 1950s, after wartime restrictions on silks, nylons, and yardage were lifted, and femmes fatales in fantasy gowns gave way to stunning yet pragmatic beauty. She considered the gold tissue lamé and breezy chiffon concoctions for Alfred Hitchcock's To Catch a Thief (1955) some of her best designs. Costume budgets were often high, and gorgeous yet accessible clothes frequently reigned.

Head enjoyed collaborating and determining costume details with her actors – she did not hand down her designs as unmovable decrees. Many of her creations were not only concerned with what was right for the character and storyline, but also about making stars look incredibly beautiful. As the 20th century progressed, the demand for meticulous, conventionally elegant wardrobes and sophisticated dressing waned. Head soldiered on, continuing to design for film characters, organize fashion shows of her costumes, and dispense dressing advice to America's mere mortals.

Edith Head would ultimately receive eight Oscars; and yet design is a group effort. There were instances when her peers felt she failed to publicly acknowledge or credit her fellow wardrobe staff – or another designer's work. As head of the design department, her industry experience and responsibilities were enormous, and she had the last word in the approval and execution of any design. Head was a designer who was widely known as a celebrity, independent of the movies she helped create, and she was protective of her persona as supreme design expert and her topmost professional position (which was precarious at times throughout her career).

The designs she either birthed or appropriated continue to surprise and entrance us. She often remarked that costumes done well could convey the storyline independently, judiciously communicating silent clues to the audience. Most importantly, these costumes remind us that clothing can act as a portal to possibility, and are not so much a second skin as the only one we show to the world.

Jill Morena is collection assistant for Costumes and Personal Effects at the Harry Ransom Center. AFS Cinema presents Edith Head’s Hollywood through Jan. 31. Tickets and details at www.austinfilm.org/series/edith-heads-hollywood.