Weekdays at Bernie's

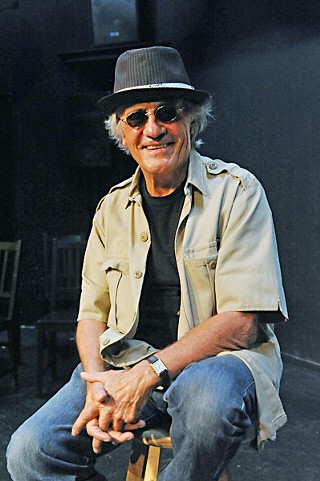

Film's best-known dead guy is alive and kicking in Austin

By Chase Hoffberger, Fri., June 28, 2013

I didn't bring the black mustache; actor Terry Kiser did. He brought the mustache for me. And alongside him, a large man named Al was fastening the thing to my upper lip with two small pieces of black electrical tape. This was necessary, Kiser said, because there is comedy where there is also a sense of vulnerability.

The mustache made sense: It was once an icon of Kiser. The veteran actor wore one in his most famous role on film: dead man Bernie Lomax in the 1989 cult classic Weekend at Bernie's, and again, four years later, in Weekend at Bernie's II. And I, a man who had never in my life acted in anything worth putting on a screen, had come to his acting studio in a black performance room at East Austin's Salvage Vanguard Theater in an effort to learn how to play dead.

"Not just dead," Kiser confirmed to his class of 12 thespians as he pulled the black mustache from his prop bag. "Funny dead."

A few motions and the mustache was on, applied to my lip, after a series of failed tries, by Al's black tape. It was joined one moment later by a pair of cheap, yellow Wayfarer sunglasses, because, in Bernie's world, you can't play dead if you're not willing to play cool just the same.

"Chase wears the mustache," Kiser explained, "because the mustache is what got me the part. I had just had a motorcycle accident, and I had eight stitches in my head. They had to shave up there, and I had a bald spot. I told [the Bernie's casting directors] that I couldn't come in.

"Months pass. I didn't leave the house much. I was doing a lot of reading. I hadn't shaved in months. They call up and say they can't find anybody for Bernie; they want me to come in. So I decide to go in."

Only he decided he'd keep the 'stache, offering to the casting directors that he'd shave it if he had to. They said it was perfect for the part; perfect for the lip of Bernie Lomax, that high-speed insurance executive who got whacked when he wound up with the wrong guys.

Joining Kiser, Al, and me onstage were two athletic-looking young actors both there to pick up my eventual corpse – today's iteration of the film's Richard Parker and Larry Wilson. Kiser, after noting the quality of the mustache on my face, instructed me to go full-limp, to slouch in ways that would get me suspended from classes in high school.

"There," he said. "Now you are dead." I felt four arms reach for my upper body, lifting my torso away from my feet. I let my feet dangle as the two actors lifted me up. My shoes scraped along the floor as they led me left, spinning me around the stage. Kiser was projecting, recalling the story he tells as rarely as he can.

"Playing dead is like our song and dance," he says, referencing a warm-up routine built around belting "Happy Birthday" with no acknowledgment of shyness or shame. "When I was playing Bernie, I saw the first set of dailies and realized that I wasn't being funny. I was just being dead. I was carrying a comedy, and I wasn't funny. So I went back to Basics 101 and said 'What if this guy was alive? What is he doing in this scene? What's going on?'

"What he's doing is goofing on his fellow players." So Kiser went full goof. The next day, he sat down on set, threw on his sunglasses, lifted his right cheek, and introduced the Bernie Smirk.

Inside the Actors Studio

To know anything about the actor Terry Kiser, you have to know about the legend Lee Strasberg.

Strasberg was director of the Actors Studio when Kiser moved to New York City in 1963, ditching his native Nebraska and a job at the Cornhusker Paving Company to board a bus with nothing but $1,500 to his name and a dream of becoming an actor. Twelve hundred miles east, he reached the steps of the prestigious institution.

Founded in 1947, the Actors Studio quickly established itself as one of the leading acting schools in the country. The studio specialized in stage theatrics – method acting in particular, by which actors assume the actual identity of the character they're playing. Strasberg was the construct's constant throughout, holding post atop the nonprofit from 1951 until a heart attack took his life in 1982. In that span, he helped foster the careers of more iconic actors and actresses than you can count on six hands – people like Robert De Niro, Dennis Hopper, Bea Arthur, and Al Pacino. "That's where all the heavyweights learned to do it," Kiser said. "If you really wanted to know about acting, that is where you went."

It was at the Actors Studio that Strasberg taught Kiser that acting doesn't originate from the characters' lines; it originates from their souls. What thrills them? What ails them? What tortured secret drives them to do what they do? Their experiences and opportunities matter just as much as the words they deliver as lines – sometimes even more. You had to stop acting and start being, Strasberg lectured. That character wasn't born the moment you walked on set.

"It's an inner craft," Kiser, 73, explained. "It's utilizing yourself, and finding out who you are. You don't have to look like George Clooney. You just have to know yourself."

Today, Kiser speaks about the Actors Studio as a safe place for his development, one that he could go to when he wanted to take chances. "This was work," he said. "It was protected. It felt back in the womb."

Kiser was a strange case at the Actors Studio, because he wasn't there to test drama – he was there to test comedy. He was such a strange case, in fact, that when he auditioned for his Life Membership in 1964, a highly exclusive honor that affords free use of the Actors Studio for as long as the individual decides to work, Kiser performed a scene from a Murray Schisgal play called Luv. If accepted, he would have been the first actor to ever achieve Life Member status on the portrayal of a comedy.

Strasberg laughed, but he'd have none of it, and he rejected Kiser's play. The acceptance came two years later on a Tennessee Williams script. Since, Kiser has enjoyed a lifetime of Actors Studio lessons and benefits playing the role of the wolf in sheep's clothing.

Kiser in the City

Kiser has appeared in so many well-known comedy movies and TV series it'd make your head spin around like a Muppet's. He was a stringer on Three's Company and The Roller Girls and worked with Bea Arthur and Betty White on The Golden Girls. He played a comedian on Hill Street Blues, held parts on The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and Blossom, and went toe-to-toe for a year and a half with the comedian Carol Burnett.

Outside of the studio, he has a 20-year-old daughter and a girlfriend named Joy who used to live in Fort Worth. He has a ranch in Colorado, and he's best friends with the singer Joe Cocker. The two convene often. They play snooker, a British variation on billiards, every chance that they get.

Kiser still acts; he does about three films each year. He has two coming out this year, one called The Pledge, currently filming, and another called A Christmas Tree Miracle, which is due in December.

"That could be a hit," he said. "Wonderful movie about a middle-class family with three kids. They sent me a rough cut of it; Joy and I sat down to watch it. She started crying. She started laughing. At the end of the movie, we both looked at each other and said: 'Jesus Christ, we could have a hit. This could be something that could last a long time.'"

He and Joy moved to Austin together in April, after a visit to Güero's and its cosmic combination of burritos, booze, and Texas blues turned the River City gold.

"We stayed here four days, walked the streets, did everything," he said. "We looked at each other and said, 'Let's give it a try.' April 1st. We had three weeks."

'Find What's Real'

Kiser's first order of business in town was setting up the Actors Arena, a modern-day iteration of the Actors Studio that Kiser designed with both comedy and Austin's affinity for film and TV production in mind.

"We're bringing the basics of true acting – the Lee Strasberg method – but we're bringing comedy into it as well," Kiser said. "The realness of comedy: how you can really be funny and not schticky."

I saw it firsthand when I stopped into the Salvage Vanguard Theater one night to audit Kiser's class. Twelve students, including Al and the two young actors who would eventually lift my corpse, gathered in a little back room along with Kiser, Joy, Joy's dog Toby, two eccentric elderly ladies who had just come to watch, and Mark Labbato, a production guy who moved from Los Angeles to help Kiser with the arena.

Kiser's students arrived carrying grocery bags and baseball bats. They brought flowers, books, and cheeseburgers. One of the two dudes who picked me up brought a motorcycle. Kiser had them all working on scenes – one-on-ones from movies like Bull Durham and Moonstruck, Garden State and The Whole Nine Yards. They'd run through a scene, take note of Kiser's suggestions, then repeat the routine twice so Labbato could film each part.

"Find what's real," Kiser advised, "and use it the way that you would use it if it was presented to you in real life. The rope is real; tie it. Toby walks up to you; let him lick your leg or don't. But don't forget to deliver your lines."

Kiser watches each scene like a ski jumper prepped inside a gate before his run. He bends forward between both audience banks, holds a railing with each hand. From his position, he hardly looks 73. He gives off 46. He lunges forward to get a closer look, wraps his hand around his chin. He applies sunglasses then takes them off quickly, and he fidgets with his hat. He laughs when there's laughter.

He says teaching's helped him improve as an actor. "You have to articulate what you're seeing," he said. "You have to articulate what's going on."

Kiser's students, all of whom have agents – though nobody in the room would claim that they've "made it" – consider him to be one of the most creative and thoughtful acting coaches they've ever worked with. He's alarmingly attentive, carries a wealth of acting authority, and genuinely seems interested in the development of these actors he's only known for two months.

"My whole intent was to teach," he tells me, "to pass on this craft that I'd learned. This was my goal: to bring this excitement to Austin. There's a class thing going on. I see an uplifting of a craft."

Learn more about the Actors Arena, including info on current class offerings, at www.theactorsarena.com.