A History of Violence

AFS Documentary Tour: 'Boxing Gym'

By Anne S. Lewis, Fri., Nov. 12, 2010

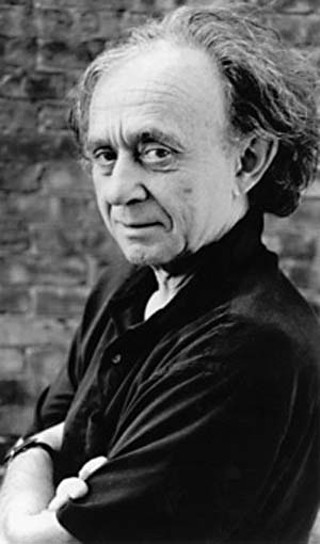

Frederick Wiseman has always disliked the terms by now reflexively applied to his oeuvre of close to 40 films – observational cinema, direct cinema, cinema verité ("pompous," he calls it), fly-on-the-wall. I suspect that, now at 80 and five decades into a career that began in 1967 with Titicut Follies (the film about

a Massachusetts hospital for the criminally insane, banned from general distribution until 1991), it's too late for new papers. A Wiseman film is typically long (hours and hours, invariably shown uncut on PBS, one of his primary funders) and made without any of the customary viewer-assists – narration, captions, talking heads. The impression is that someone simply turned on the camera and walked away, leaving it to capture whatever verité happened in front of it. But once you understand Wiseman's approach to the institutions

and ideas he's filmed, a far-ranging trajectory encompassing everything from High School (1968), Domestic Violence (2001), and State Legislature (2007) to Aspen (1991) and last year's La Danse: The Paris Opera Ballet, you see that the heavy lifting in a Wiseman film takes place during the months and months he spends in the editing room – long after the fly has left the wall. It's there that the filmmaker combs through all those hours of unmediated verité, sussing out the narrative and structure of what he's experienced.

Wiseman's latest film, the 91-minute-long Boxing Gym, was shot here in Austin at Lord's Gym, a venue similar in feel to, say, Hyde Park Gym, a place that has nothing to do with fitting into jeans, lower cholesterol, or a superior post-workout smoothie. The decor, such as it is, is hardcore – lots of duct-taped punching bags, shopworn body-building equipment, and walls lined with fraying posters of triumphant local heroes in the ring. The ambience is sweat cut with Clorox, the backbeat a continuous loop of bam-bam-bam and the shuffle of fancy footwork.

People come to Lord's to get their bodies ready to rumble. Wiseman heard about the gym and, after a short visit, decided that was where he wanted to make his boxing film. He and his cameraman spent six weeks there, shooting 100 hours of footage. With Wiseman as our guide through the Lord's Gym experience, our pre-existing suppositions about the inscrutably named "sweet science" start to fall away. It seems that amateur boxing is not the exclusive domain of macho, street-fighting guys in muscle shirts after all. In fact, a surprisingly wide demographic, from Internet billionaires to illegal immigrants, gathers at this equally surprisingly laid-back and convivial place. Lots of conventional-seeming women work out here: A nursing mother plops her sleeping infant in his carrier on the floor while she does her routine, and nearby a non-English-speaking couple sits down with gym owner, Richard Lord (who's also trained world champion Jesús "El Matador" Chávez), to discuss the feasibility of boxing lessons for their young son with epilepsy. Not a problem, Lord assures them. The point of his gym, he explains to another prospective member, a culinary-school student, is not to get into fights but to keep from getting hit.

So absorbed are we in the stereotype-busting, almost-wholesomeness of the place, the training regimens, and the sweet science's essential gracefulness – at least in its outside-the-ring context – that we're brought up short when we suddenly find ourselves ringside with two gym members going at it. The real deal. The real brutal, violent deal.

Austin Chronicle: Violence is a subject that cuts across many of your films, and you describe boxing as a form of "ritualized violence." What do you mean by that exactly? And, after your experience at Lord's Gym, what do you see as the appeal of boxing, both for those who want to be in the ring and those who like to watch matches?

Frederick Wiseman: Most of the prisoners at Bridgewater State Prison for the Criminally Insane [the subjects of Titicut Follies] were there because they had committed some of the most violent acts imaginable.Law and Order shows the role of the police in restraining violence and catching people who have done violent acts. Juvenile Court shows the sanctions applied to juvenile offenders who have committed violent or anti-social acts.Domestic Violence shows the violence that exists between men, women, and children and the role of the State inboth sanctioning and preventing it. Basic Training, Missile, and Manoeuvre are illustrations of the State's monopoly of violence in the service of protecting its citizens from external aggression. The Last Letter has as its subject the mass murder of the Jews in World War II. Boxing Gym is an example of ritualized violence because boxing proceeds according to certain established rules and forms of behavior and deviation from those rules is not permitted.

AC: What does Boxing Gym add – conceptually – to what we've learned about violence in your other films?

FW: I do not know what Boxing Gym adds conceptually to the illustrations of violence in the other films.It is simply yet another form of human violence.I am not going to speculate on the appeal of violence because all I would do would be to re-state the obvious.

AC: What is it about violence that interests you anyway?

FW: The fact that it is so common and ordinary.

AC: About your filming process, you've said that you don't research a film before you start shooting and that the shoot itself is the research. Do you at least have a question or a hypothesis in mind when you turn the camera on or do these form duringthe shoot – or only later, during the editing process, when you're looking for structure? How do you know you've shot enough?

FW: All I start with is the idea that a place would make an interesting film.I have no idea of the theses or point of view of the film until I am well into the editing, anywhere from six to nine months.I just make the totally subjective judgment that I have shot enough, probably related to being tired of motel life or living in a strange house. I also have made an evaluation of the rushes during the shooting and I make the judgment that I have enough material.

AC: And how difficult is finding "the structure" of your film in the editing room? Do you ever panic during the shooting about whether you'll find it later?

FW: The editing process is a manic-depressive special. The only thing I know is that it is best to sit in the chair and be fed intravenously until I finish the editing. I do not panic during the shooting or editing.The work is too interesting, demanding, and funto indulge in the luxury of panic.

AC: And lastly, for the record, since you dislike the terms "cinema verité" and "direct cinema," how would you describe what you do?

FW: I think I make dramatic narrative movies based on un-staged events. The editing involves summarizing and condensing the un-staged sequences to make them appear "as if" they occurred the way you see them in the final film. An event in realtime might be an hour, 58 minutes of which is shot and then the shot version is reduced in the editing to 8 minutes. But the eight edited minutes,which is assembled from different parts of the 58 minutes, has to be a fair version of the original.What constitutes "fair" is my subjective judgment about the material. I have a responsibility not to twist the material in the service of an ideology.

The Austin Film Society's Documentary Tour presents Boxing Gym on Sunday, Nov. 14, 7pm, at the Alamo Drafthouse South (1120 S. Lamar). Frederick Wiseman and Lord's Gym founder and owner Richard Lord will be in attendance for a post-film Q&A. Admission is $8 ($5 for AFS members and students with ID). For tickets and more info, visit www.austinfilm.org.

Boxing Gym will also screen at the Alamo Drafthouse South all week, with Richard Lord in attendance at Friday’s 4:05pm and 7pm shows. Both Richard Lord and Frederick Wiseman will be at Saturday’s 4:05pm and 7pm shows. See Film Listings for review.