The Mighty Finn

AFS Essential Cinema: The Chilly Humorist of Finland: Aki Kaurismäki

By Marjorie Baumgarten, Fri., Nov. 13, 2009

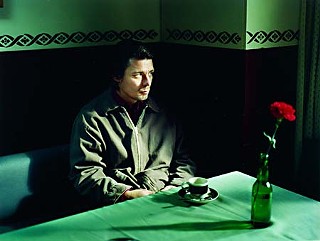

"I don't want anything from anybody. I'm Nikander ... ex-butcher, now a garbageman. Bad teeth and stomach, liver barely hanging on, which is more than I can say for my head. No use asking what I want." – Matti Pellonpää as Nikander in Shadows in Paradise

Nikander the garbageman is typical of the characters that populate the film world of Aki Kaurismäki, Finland's best-known filmmaker. Ostensible losers, often through little fault of their own, these men and women dwell in society's periphery – a periphery so large that without them society's center could not hold. They are not so much unhappy people as they are lonely, maladroit, inarticulate, or unlucky. There's no doomed fatalism hanging about these characters though. Any sense of downbeat working-class realism is ameliorated by Kaurismäki's ironic humor and life-affirming zest. The title of the new Austin Film Society series, which showcases five Kaurismäki films (a sixth, La Vie de Bohème, was shown a couple of weeks ago), aptly refers to the director as a "chilly humorist."

Having made movies for nearly three full decades, Kaurismäki has shown a productivity that is only rivaled by that of his older brother Mika, who is also a filmmaker. Though a few years younger than Mika, Aki's films were the first to connect internationally, and he achieved his first flush of widespread success with 1989's Leningrad Cowboys Go America, a film about a band with more style and determination than skill and smarts. 2002's The Man Without a Past earned the Grand Prix award (the second-highest honor) at Cannes and is probably his widest-seen film. Finland nominated it for Oscar contention; however, as a matter of principle, Kaurismäki refused to come to the U.S. for the ceremonies in order to protest America's foreign policy.

Aki may be the more celebrated of the Kaurismäki brothers because his films have great visual and thematic consistency, the hallmarks of an auteur. The aforementioned losers are always in evidence, and they generally persevere because ... well, they don't really aspire to do anything else. As Nikander says in the opening quote, "No use asking what I want." In The Match Factory Girl, all the titular character Iris (Kati Outinen) wants is to have someone pay attention to her and to be less lonely. Her assembly-line job is deadening, her home life as an indentured servant to her ungrateful parents is dismal, and no one asks her to dance at the neighborhood bar. On an impulse, she pilfers her own wages to buy a red dress she sees in a store window and goes home with the first man who asks her to dance. Things go from bad to worse, yet Iris finds her own strange way to rebalance her universe.

All the characters work at proletarian jobs, except maybe the bohemian artists in La Vie de Bohème. Ariel begins as the local mine shuts down, forcing the lead character to head out on his own. He later falls for a woman who works three or four jobs, changing from her hotel maid uniform to that of a meter maid. Jobs come and go, and characters are frequently laid off. Typical of Aki Kaurismäki's humor is the way he treats Nikander's fleeting hope for career advancement in Shadows in Paradise. Nikander is to become a foreman in a new business venture, but no sooner does he receive the job offer than the extender of the offer keels over dead.

Rare is the Kaurismäki film that bubbles with dialogue. The characters are laconic and can almost say more by gazing into the distance and lighting another cigarette. There is always music on the soundtrack, playing in the background of scenes or linking them together. It's in the music we can most directly experience Kaurismäki's love for American popular culture. Rockabilly appears to be his favored idiom, though he likes it best when performed by jangly Scandinavian groups.

Kaurismäki is often mentioned as a European soulmate of America's Jim Jarmusch, with whom he is good friends. Yet one can also detect in his work a soupçon of Robert Bresson and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, as well as a few silent comedians and a bracing touch of Jean-Luc Godard. Sam Fuller and Louis Malle both show up in cameos in La Vie de Bohème. Perhaps it's from Fuller that Kaurismäki gets his passion for brevity. He believes there's little reason for a film to last more than 90 minutes, and most of his works run more toward the 75-minute range.

Prone to downplaying his abilities, Kaurismäki contributes to his own mythology. In an interview he once said: "I am a lousy filmmaker; this I admit. But I refuse to make shit. Bad films I can make. Shit, no." Aware of his limitations in budgets and technical skills, Kaurismäki makes the most of his restrictions, and this is probably his greatest strength as a director. That and his desire to make movies that count.

Read archival reviews of Lights in the Dusk, The Man Without a Past, and The Match Factory Girl.

The Chilly Humorist of Finland: Aki Kaurismäki

Nov. 17: Lights in the Dusk

Nov. 24: The Man Without a Past

Dec. 1: Shadows in Paradise

Dec. 8: Ariel

Dec. 15: The Match Factory Girl

All films screen at 7pm at the Alamo Drafthouse South. See www.austinfilm.org for more details.