The Radical Context

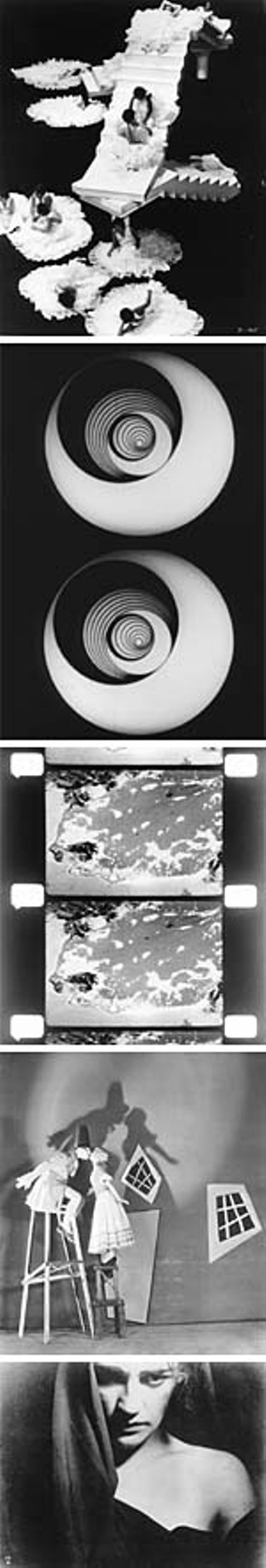

The Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center's Unseen Cinema: Early American Avant-Garde Film 1893-1941

By Rachel Proctor May, Fri., Feb. 13, 2004

It's tough to be an experimental filmmaker these days. Not only do you have to find a camera to borrow and a truckload of DV to hijack, but on top of it you've got to figure out some way to evade – rather than react to – the shadow of Hollywood. To experiment, not contradict. To be not predictably Hollywood without being predictably not Hollywood.

But in the early part of the last century, filmmakers had a much more blank cultural imagination on which to project their visions. Sure, Hollywood was there, but the sheer newness of it all meant that its formulas and conventions weren't quite so chiseled in stone. It is this period that is the subject of Unseen Cinema: Early American Avant-Garde Film 1893-1941, a 10-part film series that the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center has brought to Austin. HRC's associate film curator Steve Wilson says that the roughly 100 films, most of which are shorts, showcase an unexpectedly broad range of attempts to translate the human experience into a two-dimensional moving image.

"In the early days, any time you picked up a camera, it was an experiment," Wilson says. "Nobody had done any of this stuff before."

By "this stuff," Wilson means a lot. Unseen Cinema includes montages of ocean footage; dramatic narratives set against surreal, cubist backdrops; even the kaleidoscopic madness of Busby Berkeley musicals. In terms of genre, the Unseen films cover a lot more ground than a typical film series. But Wilson explains that the decision to cast a wide net is true to the early avant-garde, who were willing to include nearly anything in their definition of cinema.

"Before the Depression, there was a big cinema society movement," Wilson said. "Groups would get together and watch their films, which would often be home movies or travelogues, but experimental films would play in the same venue. So, there was a lot of cross-pollination."

This cross-pollination is what the curators of Unseen Cinema hoped to demonstrate. To highlight the diverse ways the filmmakers approached a single topic or technique, the curators organized the programs by topic or technique, rather than in more conventional chunks, such as time period or director. This allows viewers to grapple with the radically differing ways a well-known subject – such as New York City in the series Picturing a Metropolis or dance in Dance, Dance, Dance – can be presented.

"What can dance be on film?" asks Bruce Posner, who curated the series for Anthology Film Archives in New York. "This program shows 10 or 11 examples, and they're all different. They vary from one where hands play all the characters to numbers where actual dancers are choreographed and moving onscreen."

Wilson points out that some of the experiments on display were so "successful" that nowadays they seem utterly mainstream. He uses as an example the climax of the 1928 filming of Edgar Allan Poe's "The Tell-Tale Heart."

"These people were trying to use camera point of view or effects to show inner emotions onscreen," he says. "So, in the scene when the protagonist is being questioned in his room and he's hearing the heartbeat, suddenly there's a hammer that's superimposed. Then some words flash that are superimposed. And then eyeballs are superimposed. At that time, the Thirties, that was radical, even if it's commonplace now."

That these films are radical is one reason most of the Unseen films are enjoying their first public viewing since they were made. But there's another reason these films have remained unseen, and it can be summed up in the phrase, "film rots." In fact, it decays in a whole variety of sticky, messy, and stinky ways, so in terms of surviving prints, most of Unseen Cinema falls somewhere between the Barton Springs salamander and the dodo bird.

"This series points up the fact that our cultural heritage in moving images is decaying as we speak," Wilson says. "For 'Manhatta' [1920], the Paul Strand-Charles Sheeler film, the only print in America was deteriorated. [Posner] found another print in Europe. But there are many films that we know were made that no longer exist."

It was the HRC's possession of a rare print of "Miss Tilly Losch in Her Dance of the Hands" (1933) that first put Posner in contact with Wilson and got the ball rolling to bring Unseen Cinema to Austin. But while Miss Tilly, in her seven-minute short by theatre director and industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes, does appear in the full series, she will not play in Austin. The HRC could only afford to bring in 10 of the 20 programs in the full series, so Wilson decided to concentrate on films that Austinites might not have another chance to see. Wilson promises that Austin will get a taste of the Bel Geddes holdings soon, when the HRC unveils an hourlong piece they just spent $10,000 restoring. It's a documentary Bel Geddes made about his 1931 production of Hamlet, and for all of its historic interest, it was a film restorationist's nightmare.

"There were sections of the film where the emulsion was buckling so much it looked like alligator skin," Wilson says.

Posner, who coordinated the restoration of many of the Unseen films, says that audiences will be surprised by how well the restored films turned out.

"People think old movies are grainy and crappy-looking," Posner says. "When they see these high-quality prints, they can't believe it. These are startling, clear, vivid images of people doing amazing things."

During the 10 weeks of the series, Austin audiences will see one of the earliest gay films ("Lot in Sodom," 1930-32), a time-lapse film of a building being taken apart ("Demolishing the Star Theatre," 1901), and a screeching, howling, piano-pounding cry against the conformity of modern life ("Ballet Mécanique," 1923-24). When original soundtracks are available – as in the cacophony of "Ballet Mécanique" – they will be played; otherwise, local musicians will provide live accompaniment. Wilson says that the musicians, including the Golden Arm Trio, are still working out what to play when.

Just call it another experiment.

Unseen Cinema installments – organized by topic and technique – will screen on Thursday nights, Feb. 12 through March 11, at the Alamo Drafthouse Downtown (409 Colorado, 476-1320). Tickets are $6/$4.50 students. See www.drafthouse.com for more information.

Feb. 12

Picturing a Metropolis: NYC Unveiled (7pm)Light Rhythms: Melodies & Montages (9:30pm)

Feb. 19

Revolutions in Technique and Form (7pm)Dance, Dance, Dance: Image, Movement, Abstraction (9:30pm)

Feb. 26

Cinema's Secret Garden: The Amateur as Auteur (7pm)The Mechanized Eye (9:30pm)

March 4

The Devil's Plaything: Fantastic Myths and Fairy Tales (7pm)Writing With Lightning: D.W. Griffith, Mary Ellen Bute and Busby Berkeley (9:30pm)

March 11

Lovers of Cinema (7pm)First Steps: Early Efforts by Hollywood Directors (9:30pm)