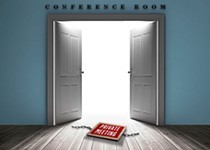

High Court Turns Back Open Meetings Act

Rules that snared City Council thrown out

By Michael King, Fri., March 8, 2019

Last week, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals ruled unconstitutional a central provision of the Texas Open Meetings Act. In a 7-2 decision, the CCA overturned Section 143, which forbids members of a governmental body from meeting privately in numbers fewer than a quorum to discuss official business as a means of evading the act's requirements. In 2012, several Austin City Council members ran afoul of that provision, signing deferred prosecution agreements after Travis County Attorney David Escamilla concluded they had created illegal "walking quorums" by regularly meeting to discuss council business, and ended those meetings lest they be subject to prosecution ("Open and Shut," Oct. 26, 2012).

"They were effectively meeting in a round-robin to avoid establishing a quorum," Escamilla told the Chronicle this week. "That violates Section 143 – or did, until this CCA decision. Several were also violating [Section] 144 – which forbids private communications in a quorum – and they were emailing each other privately."

The law includes misdemeanor criminal penalties, which is why its fate was decided by the state's highest criminal court in a case appealed up from Montgomery County, whose commissioners had been prosecuted for privately discussing a pending bond initiative with a lobbyist. The CCA's majority opinion, written by Presiding Judge Sharon Keller, found the TOMA provision unconstitutionally vague – that Sec. 143 "lacks any specificity, and any narrowing construction we could impose would be just a guess, an imposition of our own judicial views. This we decline to do."

Discussing the Montgomery County case, Escamilla said he doesn't understand why the court didn't rule, more simply, that the provision was unconstitutional "as applied" in this specific case, rather than overturning it entirely. The same question was raised by Austin attorney Randall "Buck" Wood, an ethics expert who helped draft this TOMA section back in the 1970s. "If the attorneys had asked me," said Wood, "I would have told them to treat it as an 'as-applied' challenge, not as a 'facial' challenge [i.e., unconstitutional on its face].

"As I understand the case, we never contemplated that one-on-one lobbying was intended to be barred. I've done plenty of lobbying myself," continued Wood – who was indeed a lobbyist for Common Cause when TOMA was enacted. He recalled that the specific targets of the law were extended private deliberations of official bodies, cited as a regular practice of the Dallas City Council at the time. "It was an at-large Council, heavily controlled by so-called 'charter associations,' and the Council essentially held all their deliberations in private meetings, with the public meetings only to announce decisions that had already been made." With the passage of TOMA, that practice was outlawed, with the disincentive of a criminal deterrent. "We weren't after prosecutions – we wanted to stop the activity."

The Austin case was different, in that Council members followed what they believed was a legal method for discussing upcoming agendas – without taking votes or even staking positions – and duly noted those meetings in their public calendars. After an investigation, Escamilla concluded otherwise, and without admitting wrongdoing, the parties agreed to change course to avert future prosecution. Former CM Chris Riley – a former Texas Supreme Court law clerk whose settlement agreement describes "an honest disagreement" with Escamilla over the interpretation of TOMA – was entangled in the investigation after answering questions from a constituent (activist Brian Rodgers) about Council's weekly working habits. Riley says he hasn't yet reviewed the CCA opinions, but that he can see both sides of the issue – "There is some confusion about what was allowed and what was not, and the line has to be drawn somewhere. ... Certainly it would be in everybody's interest to have clarity." He said it's arguable that the procedures that grew out of the controversy – the Council's public work sessions and regular use of a "message board" where members post discussions of pending business – have "taken a lot of pressure out of the situation we were in. If we had had that, it would have been a way to communicate with everybody."

Escamilla said he expects the CCA will be asked to reconsider its ruling, but that will likely fail, leaving future action to clarify the law to the Texas Legislature. For the moment at least, thanks to the CCA, walking quorums are not illegal, and Wood says "that needs to be fixed, and there's still time [this session] to do so." On Wednesday, March 6, Sen. Kirk Watson, D-Austin, and state Rep. Dade Phelan, R-Beaumont, announced the filing of identical bills (Senate Bill 1640 and House Bill 3402) to amend TOMA in light of the CCA ruling. In a statement, the lawmakers said the bills would answer the court's constitutional objections while providing better guidance to public officials bound by TOMA. Watson told the Chronicle, "This is a matter of high importance because members of the public need to be able to trust that decisions are being made in the open, not behind closed doors."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.