Going With the Flow

The next life of Waller Creek

By Ari Phillips, Fri., Jan. 11, 2013

To explore Waller Creek and environs is to live intensively in the modern world and at the same time to be aware of how brief an instant modernity has been with us; how brief an instant, indeed, the human presence has been here in any guise to contemplate a very old set of surroundings.

– Joseph Jones, Life on Waller Creek

In 1982, Joseph Jones published Life on Waller Creek, a meditative book about the University of Texas English professor's decades-long love affair with one of Austin's main urban creeks. For years Jones strolled the creek, taking "inventories" in which he described his thoughts and feelings while picking up trash (some of which he made into art objects) and observing the landscape – a practice that led to his appearance in Richard Linklater's 1991 film, Slacker. In the film, Jones, who had been one of Linklater's professors, talks about the tragedy of life while meandering down a street that crosses Waller Creek. Twenty years later, much of Austin is hardly recognizable – but the area around Waller Creek remains largely unchanged. Jones died in 1999, after 40 years at UT, teaching Commonwealth English literature. He was heavily influenced by American Transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, who believed human beings thrived as self-reliant individuals and should be skeptical of society and its institutions.

Life on Waller Creek is also a history of the creek, named after Edwin Waller, chosen in 1839 by Texas President Mirabeau Lamar to survey the new Capitol site and begin erecting public buildings. (In 1840, Waller was elected Austin's first mayor.) Shortly after the founding of the Republic of Texas, Lamar had sent a party of four men from Houston to locate a site for the new capital. On April 13, 1839, they reported to the president about the future site of Austin, then called "Waterloo" – a hamlet containing only two families: "The imagination of even the romantic will not be disappointed on viewing the valley of the Colorado, and the fertile and gracefully undulating woodlands and luxuriant prairies at a distance from it. The most skeptical will not doubt its healthiness, and the citizen's bosom must swell with honest pride when, standing in the portico of the capital of this country, he looks abroad upon a region worthy only of being the home of the brave and the free."

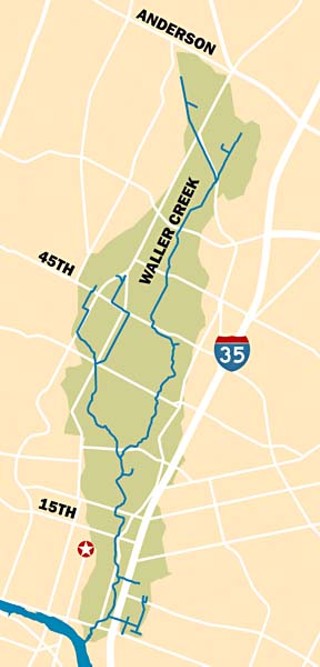

Waller Creek, in the heart of this majestic valley, is about 7 miles long, and merges from two branches along the northern border of the UT campus. The creek's watershed, just over a mile wide at its maximum, now lies mostly between Lamar Boulevard to the west and I-35 to the east. More than 50 bridges span the creek – warped wood footbridges, hefty limestone edifices, six-lane highways.

Walking the Creek

At the intersection of Seventh and Sabine streets, steep limestone embankments frame the creek and push up and into the surrounding city. During a late summer visit, the sounds of chirping birds and buzzing insects commingle with blaring radios, sound checks, and passing conversations. Pieces of white bread float in the shallow, moss-hued water, alongside plastic bags, beer cans, and darting mosquito fish. Within sight in either direction recline members of Austin's large homeless community.

Minutes before, I'd made the passage from Austin's Eastside to Downtown, crossing under the traffic-laden I-35 and entering the Red River district, home to music clubs – Stubb's, Beerland, Mohawk, etc. In the midday heat, stagehands carted amps from trailer to venue. I descended a flight of stairs and passed through the looking glass into an entirely different ecosystem: the partly subterranean, partly submerged life of Waller Creek.

Hanging vines sloped over water-stained limestone walls, and trash eddied around large stepping stones protruding from the creek's shallow water; graffiti lined the corridors passing under streets in either direction. Heading south along the stone walkway toward Lady Bird Lake, I emerged at Easy Tiger, a bar with Ping-Pong tables abutting the creek; balls floated along the far side of the creek, about a 15-foot drop down a reinforced concrete wall.

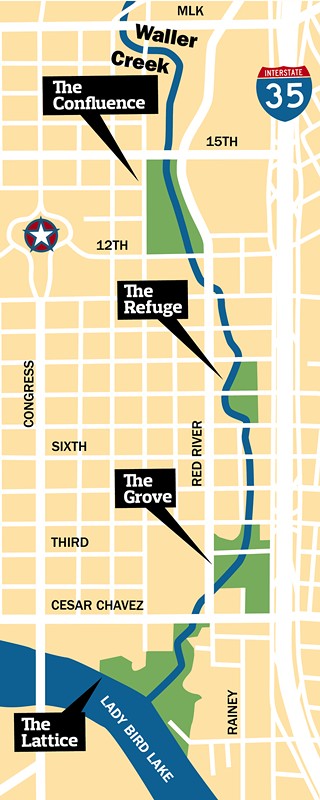

At Fourth Street, a wooden fence lined a construction site, where the extensive tunnel project that will dramatically alter Waller Creek was under way. The tunnel, scheduled to open in 2014, will relieve the creek of its biggest threat (to development) or defense (from development) – its 100-year floodplain. The flood control will allow redevelopment of about 28 acres, or 1.2 million square feet, of Downtown.

Once the project is completed, inlets along the creek will catch stormwater and send it 70 feet underground, through limestone, into a subway-size tunnel. During a storm, water from approximately 85% of the creek's 5.75-square-mile watershed will be diverted into the tunnel, which leads to Lady Bird Lake. In dry periods, lake water recirculated up to Waterloo Park via a pumping system will maintain the otherwise stagnating creek waters, and the appearance and vitality of the creek.

Just south of Third Street is Palm Park, an uninviting patch of grass and pavement between Waller Creek and I-35. An overgrown, abandoned public pool lies dormant within a chain-link fence. Two padded benches, their purple and blue vinyl shimmering in the heat, stand on either side of a lifeguard chair, just above the uncut vegetation. Ivy spilled over the fence long ago, obscuring something spelled out in bright blue fabric patches.

Slowly the words surfaced: Go With The Flow.

A sinewy man on a bike with no tires – wheels, but no tires – suddenly approached. "I've been watching you for a while. I live down here, so I have to know what's going on," he said. His jeans, far too large around the waist, were held up by string, and his soiled T-shirt, featuring a large illustration of Chuck Norris, read "Don't F&%K With Chuck."

The man said he went by "Crisco," and asked me to hold his pocket Bible while he gathered baseball-sized rocks, for hunting what he said were water moccasins. (I later learned that no poisonous snakes inhabit Waller Creek.) He charged a metal railing that separated the park from the creek, throwing rocks as the railing broke his momentum. "These snakes are really nasty; I've got to keep them scared because otherwise they come up where I live," said Crisco, as he hurled rocks at a brownish-red, four-foot snake. His camp, a dozen yards downriver in the middle of the creek bank, was little more than some clothing and trash bags.

Satisfied after frightening the snake into a half-submerged mess of trash and branches, Crisco retired under a knobby old oak to wait out an afternoon shower. He said he'd been living along Waller Creek for three years and was slowly being pushed south toward Lady Bird Lake by the police.

While the Waller Creek project is itself a giant civic undertaking, it also reflects the classic urban battle between "quality of life" and poor people, including the homeless. Austin has a homeless population of several thousand, many of whom spend time near Waller Creek, due in part to its proximity to Austin's Resource Center for the Homeless and other medical care, job counseling, and legal aid services. "There are a number of organizations at each end of Waller Creek that cause those experiencing homelessness to traverse that pathway," said Richard Troxell, president of House the Homeless, an educational and advocacy group for homeless Austinites.

Troxell estimates that about 1,000 homeless individuals use the creek corridor daily. Lately, he says, the city has been encouraging the police to keep the homeless out of the area, he believes to prepare for coming development. He imagines the future Waller Creek as much like the heavily commercialized San Antonio River Walk – homeless-free. "I think the development is a mixed bag," said Troxell. "It will sweep Austin's homeless out of the Downtown area, but if homeless service providers are smart, they'll be able to parlay the onset of the change to favorably affect the people experiencing homelessness in Austin."

Troxell thinks nonprofits aiding the homeless need to work together and plan ahead to build resources and move their organizations elsewhere; otherwise, the business community will buy them out one at a time. "If they do get bought out, the homeless community will be run over by this wave of new energy that's coming," he said. "A wave that will be very moneyed and very police-secure."

The starkest contrast between the worlds above and below is at the 15th Street bridge, just north of Waterloo Park, currently a staging ground for the main Waller Creek tunnel inlet and pump station. The tall, barbed-wire-strung planks delineating the construction site's border present a jarring juxtaposition with the neighboring Centennial Park, which that day harbored a dozen or so transients. Under the bridge, a semi-permanent homeless camp announced itself with a reappropriated "Sidewalk Closed" sign placed in the middle of the walkway. The Capitol building in the background added another layer to the composition.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.