Point Austin: Recalling Eroy Brown

Groundbreaking murder case reflects long fight for justice

By Michael King, Fri., Feb. 17, 2012

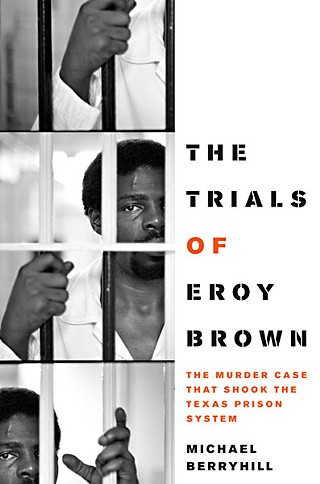

Michael Berryhill's 2011 book, The Trials of Eroy Brown, provides an illuminating study of recent but nearly forgotten state history. Subtitled The Murder Case That Shook the Texas Prison System, the book recounts the story of Brown, an Ellis Unit inmate, when he was charged with the murders of Ellis warden Wallace Pack and prison farm manager Billy Moore in April 1981. Brown didn't deny killing Pack and Moore; instead he mounted a defense that in an earlier historical moment would have been inconceivable for a Texas prison inmate: Brown claimed he had acted in self-defense. Even more astonishing, after three trials (the first ending in a mistrial when a single juror held out for conviction), Brown was acquitted – 35 of the 36 jurors who heard the testimony concluded he was not guilty of murder.

Even a generation later, those verdicts seem almost unbelievable. But the killings of Pack and Moore took place in the shadow of Ruiz v. Estelle, the landmark prison lawsuit that had recently ended in sweeping orders for reform from federal Judge William Wayne Justice. Little substantive change had yet taken place – Texas prisons remained essentially state-run slave plantations, directly managed by prison "trusties" using methods of brutal violence. But Berryhill (accomplished journalist and chair of the journalism program at Texas Southern University) argues convincingly that because of Ruiz, prison officials felt themselves under increasing public scrutiny. An angry remark from Brown that fateful Saturday apparently led Moore to believe that Brown (who worked in the prison's tractor shop) was threatening to expose Moore's (and other officials') illicit sales of prison tires and other equipment.

Brown was taken to "the bottoms" for what initially might have been a beating from Moore and Pack – but an angry Pack brought out a pistol (forbidden on prison grounds), tempers escalated, and minutes later, Brown was wounded, Moore was shot dead, and Pack was drowned in a struggle with Brown.

Payback

As Berryhill puts it, "That a black inmate could kill two white officials and not be convicted of murder shocked the prison system and marked the end of Jim Crow justice in Texas." Yet over the ensuing decades, Brown's trials and their significance have been lost in the shadow of the Ruiz case and the Judge Justice interregnum, which broke the trusty system of prison management and forced the Texas Department of Criminal Justice to professionalize and move out of the state-plantation dark ages. Plenty has been written over the years about Ruiz and Justice, but Berryhill's book is the first on the Brown case.

Brown was freed, but he soon returned to prison as an accessory to a $12 robbery – and was sentenced to 90 years as a "habitual criminal," although he and his lawyers are convinced that his real crime was "defending himself against two Texas prison officials in 1981." He is serving his sentence in federal prison to prevent retaliation; now 60, he's eligible for parole he's unlikely to receive – current and former prison officials do what they can to prevent it, including persistently misrepresenting the evidence and trial record that Berryhill carefully sets forth here.

Brown was defended by legendary Houston state Rep. Craig Washington, and his performance is part of the permanent record of civil rights victories. Another of his attorneys, Bill Habern, told the Austin American-Statesman concerning Brown's pending parole decision: "The system still to this day doesn't believe he should have been acquitted. What is probably going to happen is called getting even."

Race Matters

I would like to be able to write that Ruiz transformed Texas prisons once and for all, and that the Brown case became a permanent lesson that even Texas inmates can expect equal justice. Brown's acquittal for murder was undeniably a victory; his subsequent personal history confirms that much remains to be done. More broadly, the prison system that came out of Ruiz and its aftermath has exploded in size and scale, slowed only a bit by the recent recession.

In 2010, Robert Perkinson, author of the prison history Texas Tough: The Rise of America's Prison Empire, told me that Ruiz brought to Texas prisons some professionalism and better conditions, but it was followed by radical expansion of drug laws, incarcerations, and sentencing, strongly biased by race (see "Grim History," Aug. 20, 2010). Perkinson wrote, "Today, a generation after the triumphs of the civil rights movement, African Americans are incarcerated at seven times the rate of the whites, nearly double the disparity measured before desegregation." Yet white politicians continue to campaign as though racial inequality were an ancient relic. Indeed, the Republican presidential candidates attack the first nonwhite president in flatly racial terms, and treat minority voters – in rhetoric and in policy pronouncements – as though they are de facto criminals who should be presumed guilty until proven innocent.

The past, as William Faulkner wrote, is not dead. It isn't even past. We have yet to travel far enough away from the plantation history of Texas – nor that of the rest of the USA.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.