The Future Is Now

Local fiscal policy enters its cold war era

By Mike Clark-Madison, Fri., Aug. 13, 2004

"Is this a sunrise or a sunset?"

That's what Council Member Brewster McCracken asked when the City Council got the first of this year's budget presentations on July 30 – featuring, in its opening slide, the red-skies graphic at issue. "Oh, it's definitely a sunrise," City Manager Toby Futrell replied. "The message is, 'Hope is on the way.'" (This was the mantra of John Edwards' convention speech the night before.)

There's no cocky banner hanging at City Hall for Futrell to later regret, but unlike Our American President, the Austin city manager can credibly claim to have finished what got started on 9/11. As the world reeled in shock that morning, the Austin City Council gave its final approval to a fiscal 2002 budget that had already been rendered worthless by current events. Thus began what Futrell, in presenting the latest city spending plan, dubbed a "four-year financial odyssey" – The Heart-Breaking Saga of the Incredible Shrinking City General Fund – that this year, we can only hope, reaches its denouement.

So is the "fiscal war without end" (as we dubbed it last year) in fact at an end? No. It's just going on by other means – you might call it a Budget Cold War. Neither Futrell, nor the City Council, nor the citizenry are yet willing to accept that the current level of city service delivery is where Austin wants to be. But the likelihood that city revenues will grow as fast as they have shrunk – in other words, that we'll have another steroidal boom – is probably nil. It will probably take at least 10 years to "rebuild" to where we were on 9/11, long enough to make relevant the question of whether "rebuilding" is what we want. Or do we want a different kind of government, with different priorities? And what would those be?

And who do we want to do the rebuilding? Most other local governments aren't as battle-scarred as Austin's, but few have remained unscathed. And most of the big issues and top stories of our day – the city-county fracas over the hospital district, the battle over toll roads and/or Capital Metro, the ups and downs of Hill Country subdivisions and suburban big-box retailers – are themselves budget battles, between jurisdictions, on a regional scale, fought over how to share money and power over the same body politic. Compared to the Balkanization of past decades, the route through which we ride the recovery will not be charted by City Hall, or any other center of power, in a vacuum. The sun may be rising over Central Texas, but the day ahead should be a very long one.

The Reinvention Begins

"We had just passed the FY 02 budget when the revenue stream went completely dead," Futrell recounts. "We went into heavy cost containment immediately and have now been in that mode for four years. That's a long time. But we've now had six months with positive leading indicators everywhere. Sales tax collections are still fluttering, but in the positive range. Property values are holding, job creation is beginning, building permits are being pulled. We're on the edge of the movement up."

Futrell's FY 05 budget is a lot more promising that she, or we, or anyone else, had expected last year at this time – when, after two years of "cost containment," she whacked another $40 million in city spending and laid off nearly 100 people and cut more than 300 General Fund positions in the FY 04 budget, all the while warning that this summer would be just the same. When that budget was adopted, and for months thereafter, the City Hall mood – despite signs of economic recovery – remained dour; in March, Mayor Will Wynn complained about "staring down the barrel of an imminent $45 million budget shortfall."

Two months later, when Futrell inoculated the council and citizenry with her FY 05 "draft policy budget," the darkness had dissipated substantially. But still, the city manager forecast a $19.4 million General Fund gap to be bridged with yet more spending cuts (assuming – accurately – that the council wouldn't support a more-than-nominal tax hike or a less-than-judicious raid on the city reserves). Ultimately, Futrell noted, city General Fund spending is guaranteed to increase $30 million a year, thanks mostly to the generous public safety pay packages approved during the boom. Since the easiest offsetting cuts had been made in prior years, even a $20 million hit would have likely meant more layoffs, more closed facilities, more reductions in services, and more rending of garments. In the draft policy budget, Futrell helpfully and graphically pointed out just how bare City Hall's bones already were.

Though hardly pleased, the council seemed ready to, in Council Member Daryl Slusher's words at the time, "suck it up and pass another tough budget. We have to not let the pain – the cuts that we'd rather not make or the additions we would like to make – get in the way." So when the actual budget came out with cuts of closer to $11 million – thanks to growth in sales tax revenue and continued Capital Metro funding for transportation projects – and a net reduction of only two positions, and the first pay raises for city employees in three years, victory was swiftly declared. Out of a General Fund of more than $470 million, most of which is either practically or politically untouchable, $11 million is real money, but not a Grand Guignol fiscal horror show. (The $470 mil includes funding that will, in reality, be part of the still-to-be-finalized budget of the Travis Co. hospital district.)

As Futrell aptly notes, the most important question facing the City Council now is "What will you do with your first new million?" "It's clear to me that in [fiscal] 2006 we're going to be in rebuilding mode," she told the council July 30, and "the question of the day [is] how this council prioritizes where they want to add back, and how they want to start rebuilding. Not just new initiatives, but will we add back a day to our libraries? There are so many questions to ask. So the dialogue for this year needs to be how we add resources back strategically."

Which is another way of saying that "rebuilding" may be a misnomer – "reinvention" is probably a better bet. Some former fiscal pillars and landmarks will never be rebuilt, or will take on new, unrecognizable forms. Witness Futrell's re-re-re-re-organization of the city's planning and development functions, creating a "one-stop shop" bringing development review staff (formerly housed in 13 separate departments) into one physical and bureaucratic locale at One Texas Center; likewise centralizing code enforcement into one shop within Solid Waste Services; creating a real 24-hour 311 call center for citizen complaints (instead of the weak little thing that goes by that name now); and dismantling the Transportation, Planning, and Sustainability Department.

Futrell has made quite clear that she's used the budget crisis – the need to make One Texas Center cheaper and more efficient – as political cover to throw one of the hottest of Austin's hot potatoes into the trash for good and all. That first new million might indeed go to neighborhood planning or code enforcement – both areas that have never been flush with cash – but the fiefdoms of yore will still be gone, and TPSD will still be D-E-A-D. There's probably more hardcore budget-shuffling to come elsewhere in the General Fund; the hefty operating costs of, say, a new central library, or of the fully-built-out Town Lake Park and Colorado River Park and Eastside "destination parks," will likely have to be offset by reorganizing those departments from the ground up, closing existing facilities (or at least not building any new ones) and otherwise going beyond "efficiency" into the realm of politics.

These decisions will hardly be easy, gentle, or pleasant. In the new Budget Cold War era, all local governments will have to justify what they spend, not just in terms of what they used to spend, but as a function of what citizens are willing to pay for. Former Mayor Kirk Watson likens the new paradigm to the process of setting a bond election, rather than the usual public-sector budget drill. "It will shift the focus of budgeting to what service the public wants, and at what price, and build from there," he says. "Then the public knows it's getting what it wants, and focuses less on the costs."

That sounds obvious, but even four years of crisis have not brought City Hall around to actually making the "hard choices" and "forced tradeoffs" so prominently featured in local political rhetoric. "I would like to see our budgetary dynamic changed, but the fact is there's not broad support for large-scale change," says Wynn, who last year raised the possibility of permanently closing "beloved" city facilities – parks, libraries, fire stations, what have you – to focus resources on the rest. And "a possibility" it remains.

A Spender's Market

As City Hall has gone through its public agony, Travis County – with a $334 million General Fund budget of its own – has been lucky. "After 9/11, the county budget did not go down the drain," says County Commissioner Karen Sonleitner. "The bad thing is, all we get is property tax" – the county collects no sales tax and has no "enterprises" like Austin Energy to feed the kitty. "But the good thing is, all we basically get is property tax. Counties have a great deal of certainty about their revenues, and 98% of the money you get for the entire year is in by February 1. So there are no surprises on the revenue side."

Even though the Travis County (and, by extension, Austin) tax roll declined for FY 04, and will grow below the rate of inflation for FY 05, both city and county can offset the effects by raising property taxes to the "effective rate," as they are again this year. (In the budgets currently on the table, the effective rate is about a 2% jump, compared to the nearly 8% it equaled last year.) But property tax only represents about 30% of the city General Fund, and more than 80% at the county. (Various fines and fees – primarily court costs of one or another kind – make up the rest.) Though last year Sonleitner and the Commissioners Court did adopt what, in county terms, were significant General Fund cuts, the amount was a pittance compared to what Futrell left on the floor.

But with the state and feds ruthlessly down-shifting public costs below the line of sight of their suburban GOP supporters, the county has its own challenges and choices to make. Sonleitner qualifies her assessment of the county's fiscal stability – there are no surprises "unless the Legislature goes into special session and starts talking about revenue caps, or new unfunded mandates, or passes new laws in the middle of a fiscal year." Hence the "bad news" component of dependence on property tax, with Gov. Rick Perry and his allies talking trash about "property tax relief" that would limit appraisals and thus hamstring county finances forevermore.

As is well known by now through the hospital-district imbroglio, the city, and not the county, has for generations paid the lion's share of local public-health costs, even for out-of-city residents. However one may quibble about their relative shares, though, both city and county spend a lot on human and social services and for public safety – and the county, with sole responsibility for the civil- and criminal-justice system, unfortunately picks up a lot of the costs for the bodies that fell through the safety net. "That's the tough nut of this government," says Sonleitner. "We cannot predict the number of capital murder cases, or the number of indigent defendants needing an attorney who are guaranteed one by law, or how many inmates will be in our custody either pre- or post-adjudication, or how many poor people will wind up in our health clinics."

It's true that, comparatively, the city's finances – except for the health-and-human-services functions it shares with the county and, now, with the hospital district – are less sensitive to actual demand. City police and fire spending, the largest component of its General Fund, does not automatically fluctuate as the number of crimes or fires or accidents goes up or down. But spending in the courts and corrections system, the largest components of the county's General Fund, does fluctuate just so. "We're in the criminal-justice business," says Sonleitner, "and we never break even."

The same dynamics are in play, even more acutely, in the largest tax-supported budget in the region, that of Austin Independent School District. The district is caught, even more than other Texas districts, in the limbo left by the Legislature's dithering on school finance, serving a growing and increasingly needy student body, spread over a growing geographic area, with a revenue stream that's been capped, and indeed reduced, by Robin Hood. This has forced AISD into fiscal poses that you'd never see struck at either City Hall or the county courthouse – like pushing small-scale capital expenses, the kind the city and county make a point of paying with cash, into bond packages like the one coming up next month, or dipping into cash reserves to pay ongoing expenses, like employee compensation increases in the district's proposed FY 05 budget. From a policy standpoint, this is unsustainable by definition, but everyone knows AISD has no choice – for now. Soon, it will have to choose.

And then, groaningly, there is transportation, the No. 1 concern of the citizenry, a battleground where the fights are all about money, regardless of your feelings about cars and trucks and trains per se. Though a transportation network can and must blow past jurisdictional boundaries, no single entity – not even the Capital Area Metropolitan Planning Organization – coordinates, let alone decides, where and how all the transportation dollars are spent, let alone where they come from. Hence the acute pressure on Capital Metro, and now on the Central Texas Regional Mobility Authority, to cough up the cash to pay for other people's projects, including each other's projects, whether they want to or not.

A New Regionalism Rising?

Most local leaders, and many of their citizens, seem to understand, however dimly, that the budgets of the city, or county, or AISD, or Cap Metro and the CTRMA – or the state and feds – are not just policy documents for those entities alone. What one does affects the others, as the hospital district is now finding out, and they all affect the taxpayers that support them.

The weight of the region's overlapping tax burden, in the face of its escalating cost of living, has long been cited at City Hall – since long before this decade's budget crisis – in explaining Austin's artificially low property tax rate compared to other Texas cities. As Futrell explains it in this year's budget, while the city's share of the overlapping property tax bill is only 18% – much lower than in other big Texas cities – Austin ranks at the top when the tax bill is expressed as a percentage of median income. (Conversely, Travis Co.'s share of the bill is much larger than that of most urban Texas counties, but even if it weren't, it would likewise be the highest relative to income.) "Even in good economic times," says Kirk Watson, "people felt like they were being taxed too much. We knew we had a high cost of living, and we could help control that at the local level by not ratcheting up the tax rate."

The same perception, though not always the same tax policy, holds true for Travis Co. and Austin ISD, leading to annual angst when it's time to set tax rates. "What works for Travis County may not work for AISD nor the city; each government needs to be able to respond to the mandates and demands of their constituents," says Sonleitner. "Of course those constituents are one and the same when the bill arrives. But when the schools are in crisis, the county can't just open up space on the tax bill and ignore its own mandates and responsibilities."

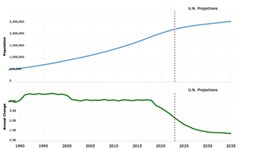

According to the Real Estate Council of Austin's annual "Combined Cost of Governments Index" – which factors in the city, county, AISD, and ACC property tax burden, the city and Capital Metro's sales-tax take, and the city's General Fund transfer from its utilities – the local-government price tag has grown nearly 140% since 1989, while median income has only gone up 84%. The relative gap between the two has been even wider since 2000, with total government costs going up more than twice as fast as incomes.

Of course, RECA sees this as prima facie evidence of fiscal irresponsibility, whereas others may find it obvious that economic hard times lead to more people in jail, more patients in the emergency room, more kids failing the TAKS test, and thus higher government costs. But the point is nonetheless made across the political spectrum. "I don't think local government, in the foreseeable future," Watson says, "is going to enjoy having more money than it feels like it needs to balance the budget." The only exception would be Capital Metro – if rail again fails – but that money (half of its total budget) is sure to be commandeered by the road warriors, and despite the hype, we're talking about maybe $60 million a year, out of a collective local tax burden of some $1.8 billion.

With every local government feeling it has shed its excess body fat, or must respond to inexorably growing costs, or both, there really are few opportunities to make the tax hawks happy. One obvious next step is merging what are now separate budgets into one. "We need to seize the opportunity to pick up some consolidation of services because, frankly, it's easier than it was 10 years ago," Watson says, because of both "the transition we're going through, to regionalism, and the sustained revenue challenges faced by local government. We have some opportunity."

But one need look only at the hospital district to see that "easier" is not the same as "easy." Sonleitner – among the city's harshest critics on that front – nonetheless sees positive examples of collaboration, if not consolidation, between City Hall and the courthouse. "We can, and should, and do work together on economic development issues that bring good things to the region as a whole," she says. "All governments benefit from the payroll taxes being paid, new homes being bought, and general goods and services being bought and consumed."

In truth, the opportunities for unified government, or at least a unified government agenda, are immense – whether it be partnership between Cap Metro and the CTRMA, or AISD and the Austin Public Library, or Austin police and the Travis Co. sheriff's office. But few topics better illustrate the fact that government cannot, in fact, be run like a business. If governments consolidate their services, they can downsize, but they can't sell off redundant departments to someone else or churn their way into a different market, and going bankrupt is considered rather unseemly. When one software company merges with another, and they both offer products that do the same thing but in different ways, they simply choose to support one and orphan the other. But if, say, AISD and Austin Public pursue joint-use libraries, they have to be both city and school libraries – and thus would be more expensive to operate than either one standing alone, though cheaper than the combined cost of two standing alone. That, writ large, is a main challenge facing the hospital district, even though many city and county health functions have in theory been "consolidated" for many years.

Given that fact, it's been a lot easier to talk about economic growth and job creation, in vague enough terms to suggest a new boom – less robust than before, but strong enough to turn the upcoming Cold War into peace. But even that happy subject is fraught. "I worry about replacing the economy that's changing in our city," says Futrell. "What will replace chip manufacturing here? When 30,000 or 40,000 jobs just go away, what replaces them? What is the new economy for Austin? How do we build it and attract it? How do you make an economy in which all boats rise?" ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.