Under One Roof

Can the City Make Good on Its Affordable Housing Promise?

By Kevin Fullerton, Fri., July 28, 2000

Isn't it about time we discarded this term "affordable housing"? Raise your hand if you think your rent or house payment is too high for what you're getting. Uh huh. Now, who's given serious thought to fleeing this insane real estate market and moving out of town? Maybe your hand didn't go up, but your mailman's might have. Once upon a time, subsidized housing assistance in this town was typically for those who for whatever reason couldn't sustain gainful employment. But now that the cost of living is putting the squeeze on more than 200,000 Austin residents, most with perfectly respectable jobs, the stigmatized "affordable housing" label seems less appropriate than "housing continuum" -- a range of affordability that allows techheads and wage-earners to share the same ZIP code. Otherwise, as representatives from San Jose and other undesirable burgs have repeatedly warned us, the workforce -- not software designers, but our far more numerous cashiers, nurses, and laborers -- will get pushed out of town, which in turn exacerbates road congestion, segregation, and a host of other ills.

Two years ago, when the city was seducing Computer Sciences Corporation to a downtown office site, public officials talked a lot about doughnuts: cities like Detroit that had allowed commercial activity to escape outside their borders, hollowing the tax base and ghettoizing inner-city neighborhoods. Since then, the mayor and City Council have "incentivized" not only CSC but also Intel to the Central Business District, recently investing in a Convention Center hotel to boot. The city seeded $10 million here, $15 million there, and presto, downtown development took off. Yet when it comes to preserving our human capital in the urban core by promoting the construction of entry-level homes and apartments affordable on working-class incomes, we pat ourselves on the back for committing $1 million here, $1 million there. Don't think developers haven't noticed.

"See, this is what I'm talking about; they can make things happen," one developer complained last year as the City Council was flirting with the audacious proposal to build the 120-foot, luxury Gotham condominiums tower next to Town Lake. Two years before, the council had given in to neighborhood protests and nixed an apartment complex that same developer had proposed for lower-income tenants in East Austin. "They could help me, too, if they decided it's what they really want to do."

It's easy to see why the council would make downtown development their headlining act: It's sexy, it's symbolic, and it offers captivating public amenities to make the hoi polloi feel included. It has also helped reinstate the appeal of urban neighborhoods as the place to live, work, and play. For all but the wealthiest among us, however, the downtown scene is little more than a showcase locked behind plate glass. And while the city has been out doing business with large employers and high-end apartment builders, it hasn't even been paying the salaries of the city housing employees who work with the private interests that can actually make things happen for real people. The most effective prod Austin has to get bankers and builders in line with the city's massive housing needs, the Austin Housing Finance Corporation (AHFC), is essentially a bastard child surviving on yearly federal grants (see sidebar, p.28). "This council is more committed to dealing with the issue of housing than they've ever been before," says city housing director Paul Hilgers, "[but] I don't think we've ever had the policy direction from council to become more actively involved, to find a way to leverage our resources so we can turn some money back out into the community."

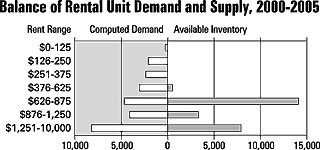

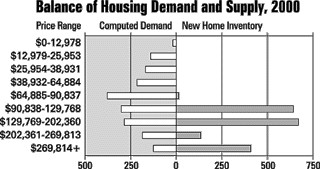

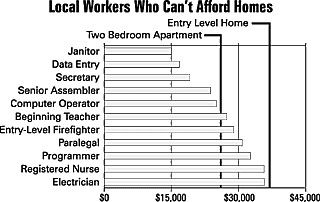

Admittedly, addressing the housing crisis can provoke a certain hollow dejection. With more than 2,000 people already on waiting lists for public housing, and dozens of new people arriving daily whose wages won't earn them even the cheapest two-bedroom apartment, Austin can't possibly meet the demand for low-cost housing (see charts, p.24). For every new executive position created in this town, there's also a cashier, a waiter, and a sales clerk. Putting up this tide of newcomers immediately is no more feasible than the Army trying to erect barracks for a landing paratroop division. Things are going to be messy for a while. And manufactured home dealers in Del Valle are going to stay busy.

The bigger question is whether Austin will like the way it looks after this shock wave has passed. When only about a quarter of the new homes in the area are being built inside the city limits, Austin is obviously not in control of regional development -- the builders are. And we know what happens when the private market builds the housing stock its way: closed-off communities in West Lake Hills, and lean-to camps in Indian Hills that crumble into squalor before they're even built out.

Wouldn't it be nice if this time we could at least build some true neighborhoods, ones that afford dignity to rich and poor alike? "We've been able to do it for the classes," says one housing official, referring to new residential development downtown, "but can we do it for the masses?"

Neighborhood Renewal

Actually, efforts to reclaim Austin's poor neighborhoods have been going on for several years, but on a scale so small it's easy to miss. Saturday, July 15, was Community Awareness Day in the Springdale neighborhood, a predominantly black enclave rimming Springdale Park, south of Martin Luther King Blvd. and just east of Webberville Road. The event was much more than just a fire-truck display and rows of booths set up to spread pamphlets. City Council members were out, as was Travis County Commissioner Ron Davis and U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett.

The occasion? A celebration of 40 new homes built nearby by American Youth Works (formerly the American Institute for Learning), a nonprofit that employs students enrolled in its charter high school as carpenters on its projects. The setting was humble -- with speeches given from the front porch of a shotgun shack once inhabited by drug dealers, that's since been reclaimed as a day care center by the True Life Missionary Baptist Church across the street -- but the residents and elected officials radiated genuine pride. The crack houses are mostly gone from Springdale, and young families have moved into roomy new homes with prominent gables and wide porches. Trash has disappeared from yards, and fresh paint gleams even on older homes. Even the neighborhood HEB has gotten a facelift.

"I just cried through all this stuff," True Life pastor J.R. Williams told the crowd, remembering the six years since Youth Works executive director Richard Halpin approached the church about building homes on lots that it owned. With help from the city's office of Neighborhood Housing and Community Development, Youth Works purchased the lots with a federal grant, then sold them for between $69,000 to $85,000 to low-income families. Monique Young, who grew up in Springdale, is working on a new Youth Works site there now. "It used to bring me down to come over here," she says, but now "kids have a lot of things they didn't have before" in this neighborhood.

Source: Capitol Market Research, March 2000, October 1999. The percent of households by income group is calculated using inflation-adjusted income data and the distribution of income based on the 1990 Census.

The Youth Works project is neighborhood revitalization at its best, explains housing director Hilgers, driving past a new house whose walls are being framed with straw bales. These houses, he says, are "triple-hitters" -- affordable to the residents, built by at-risk youth, and, as a bonus, highly energy efficient. But what's most fascinating about Springdale is what hasn't even happened there yet.

Hilgers drives east on Hudson and in less than two minutes arrives at Ed Bluestein Boulevard, driveway to such mega-employers as Samsung, Motorola, and IBM. The houses disappear quickly, replaced by vast tracts of vacant land covered in thickets of trees. The infrastructure out here is questionable, Hilgers says, but the location is prime. Though we're in what's known as "far East Austin," a wilderness neglected for half a century by the real estate community, we're only 10 minutes from downtown, closer to the Capitol than Tarrytown, and right near Johnston High School. In some respects, the Eastside is a developer's paradise: Poverty it has in abundance, yes, but also magnificent trees, parks, and greenbelts untrammeled by tacky subdivisions. Yet throughout East Austin, whole swaths of real estate, including more than a thousand developed lots, lie fallow.

Until recently, only the Austin Housing Finance Corporation and neighborhood nonprofit developers like Youth Works took any interest in that land. Over the past two years, the AHFC has purchased 50 of these lots, donated them to builders who put up three-bedroom homes costing around $65,000, then offered zero-interest down payment loans to the new owners. Lately, AHFC has gotten more entrepreneurial, contracting out the construction but selling the properties itself, so that the income from the sale revolves back to the AHFC for further acquisitions.

But in the past year, the AHFC and other small nonprofits in neighborhoods such as Blackshear and Guadalupe, who have been fighting urban decay one foundation at a time, have run head-on into East Austin's resurgent real estate market. Ten years ago, lots could be had for a pittance, but lately they're getting snapped up at prices that make low-cost construction unfeasible. And many more, perhaps as many as 1,800, are either tied up in tax arrears or lack clear title -- fallout from the 1980s bust that rendered lots so worthless that inheritors refused to claim them to avoid the taxes. Local taxing entities -- the city, county, and school district -- have not been able to agree on a way for properties with delinquent taxes to be foreclosed upon without putting them up for auction on the courthouse steps, where AHFC and private nonprofits are getting priced out. But those entities have formed practically the only residential revitalization force in East Austin, which for 30 years hasn't seen one major single-family development built north of Town Lake.

Roadblocks to Development

The future of East Austin -- our remaining urban frontier and perhaps the best hope for centralized, integrated neighborhoods -- is very much up in the air: too expensive for its residents to live in, yet too depressed to attract speculation. Bill Howell, who by his estimate is one of only two developers still working big projects in the central city, says the city of Austin will have to change its attitude before any big developers are going to take a chance on the Eastside.

Howell is a bulldog of a man who's been around the block a time or two with the city's Land Development Code. Standing on the rim of one of his latest projects, Kinney Court -- soon to be 59 new homes just southeast of Lamar and Oltorf -- Howell says it required 27 variances and waivers, plus the generous assistance of a City Council member, to get the development on the ground. Like other developers nationwide, Howell has caught the New Urbanist fever: Kinney Court is all two-story houses, packed in twice as densely as in a typical suburban subdivision, fronting a narrow ribbon of pavement with a small park at one end.

Source: Capitol Market Research, March 2000, October 1999. The percent of households by income group is calculated using inflation-adjusted income data and the distribution of income based on the 1990 Census.

Howell says doing infill development in Austin is a major headache and expense, but at 60, he now prefers projects that do his name proud to projects that maximize returns. "When this is finished," he says, gazing down the road that loops through the forest of white masonry, "I want to take my momma and drive her through here and say, 'Lookee what I did.'"

Not that there still isn't room to make a profit. Howell can sell lots in this rapidly gentrifying pocket of ranch-styles and duplexes tucked between Lamar and South First for more than triple what they cost to develop, and he's turning dozens of them. The buyers are young professionals who want to be near downtown and don't want a yard that takes all afternoon to mow, says Howell. Homes in Kinney Court start at $200,000 and go well past $300,000. Howell says that his influx of expensive homes, designed to blend in with their older neighbors, will ultimately save this decaying neighborhood. "I guarantee you that every house within two blocks of this development will be completely redone, painted, and cleaned up within two months of the completion of the first house," he says. "It's just amazing."

When vacant land in the Bouldin Creek area is all used up, Howell says -- probably in another two or three years -- he'll turn his attention south, past Ben White. Homes won't sell for as much down there, though. And East Austin? Any chance the cotton-row houses Howell has brought to South Austin could be scaled down for Eastside incomes? Howell says that he tried that once, in 1997, but he didn't get far because the complications outweighed the benefits. He's not ready to go back. Howell drives around to the rear of Kinney Court and stops by a huge depression ringed by a wire fence. It's 12 feet deep and takes up half an acre -- about five lots' worth of land. In drainage parlance, this is what's known as a retention pond. Howell had to build two of them for Kinney Court. When you subdivide old lots, he says, city regulations require one pond per structure, and that rule applies to the lowliest property as well as the most expensive. The price of gutters and streets, meanwhile, is twice as much per foot in Austin as it is in comparable cities, Howell says, so a typical lot costs about $14,000 to produce.

By rule of thumb, then, a house placed on that lot would have to be worth about $70,000 just to recoup the investment, for a total sales price, no profit included, of about $84,000. The 5-to-1 ratio between the cost of the lot and the value of the home is not about profit margin, says builder Richard Huffman, who has built entry-level homes on lots purchased by AHFC. The ratio is necessary to square things with the county tax assessor, he says. Building a house that's too small for a lot reduces the improved value, Huffman says, making it highly unlikely a lender will extend credit to a potential buyer. But an $84,000 home -- not that it could be purchased that cheaply -- is already out of reach for many working-class incomes.

Policy Rigamarole

Policy wonks can argue until they're blue in the face about whether the city should continue to impose rigid impervious cover and drainage restrictions. Indeed, revising the Land Development Code was supposed to be Jackie Goodman's sole raison d'être for her last term and a half on the council. But the bottom line is: Developers don't want to fool with them, unless they can build luxury homes. And builders like Huffman who specialize in entry-level homes are about out of options in this town unless they partner with the city, AHFC, or other nonprofits that can access low-interest loans. Howell says developers today are still paying for the flawed flood-control policies of the past. "We're resolving problems for development that was done 40 years ago; [the city's] putting that onus on us, and still asking us to come to town," he says.

The AHFC coordinator for economic development services, Martin Gonzalez, says city policy impacts developers in another big way. Developers have to absorb all the upfront costs of installing water and electric lines on new lots, later getting reimbursed by the city, at cost, for their expense. That means, explains Gonzalez, that developers are essentially financing the cost of the city's infrastructure at prime lending rates. In municipal utility districts, by contrast, (where, as we all know, development in metropolitan Austin has flocked for the past two decades), infrastructure gets financed at a much lower interest rate through the sale of revenue bonds.

The city could implement a similar plan for the central city, Gonzalez suggests, except that it would lead straight into a bona fide Austin bogeyman: higher utility rates, as customers absorb the cost of servicing bonds issued through the electric and water utilities. In fact, Austin tried this approach some 20-odd years ago after it rolled out the Austin Tomorrow Plan, which laid out a Desired Development Zone much like the one we know today. Voters were asked to approve a bond sale that would have financed new infrastructure in that zone, but they nixed it. Developers subsequently headed for the hills.

Development costs, in fact, are threatening to choke the affordability right out of a 13-acre tract the city purchased in 1998 off East Riverside Drive along Frontier Valley Drive. For the bargain price of $75,000, the city rescued the land, known as the Montopolis Tract, from being turned into another suburban trailer park, hoping to build a community of mixed-income properties. As the construction market stays hot and interest rates climb higher, however, the city is finding out for itself that it's difficult to build housing that's affordable to poor residents, on even an inexpensive piece of land. The exact cost of proposed units on the Montopolis Tract hasn't been released yet, but housing officials say the numbers are tight.

However, the city is about to test-drive a vehicle designed to help developers not only put up lower-priced homes but piece together the kind of mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods everyone knows we should have. Created as a detour around the city code restrictions that have infill developers like Howell pulling their hair out, the Traditional Neighborhood Development (TND) ordinance allows developments of at least 40 acres to have narrower streets, smaller setbacks, integration of single-family, rental, and commercial uses, and more flexibility in meeting impervious cover limitations.

TNDs to the Rescue?

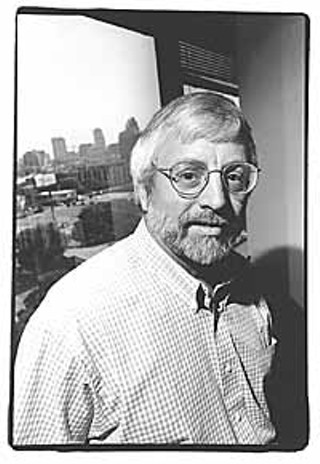

The first builder to take the TND plunge is Milburn Homes, a longtime specialist in entry-level home construction that's ready to gamble $60 million that Austin, even working-class Austin, is looking for a denser, more interconnected kind of subdivision. "Right now, most of the development you see happening is apartment developers doing apartments, office builders doing office, industrial doing industry, and they don't even pay attention to connectivity to themselves," says Milburn vice-president Terry Mitchell, one of the primary authors of a 1999 task force report that described the city's home affordability challenges. "But they haven't really said, 'If this was your own little city, how would you want it to be so that it worked together?' That's the experiment for us, to see if that does work better."

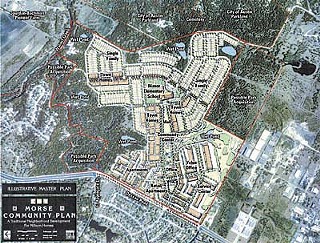

In partnership with JPI, which will build apartments, and Scott Young, noted for his retail tour de force in the Lamar-Sixth Street area, the Milburn proposal on the Morse tract in Northeast Austin (see rendering) includes 400 homes, 180 townhomes, 280 apartments, and 300,000 square feet of commercial space on 250 acres off Dessau Road between Rundberg and Braker. In the heart of this development will be a brand-new Manor elementary school. The price of Milburn's homes, Mitchell estimates, will start at around $90,000 and go up to $200,000 for structures of 1,200 to 1,900 square feet.

Mitchell promises that the development won't mirror our parents' auto-centric, suburban subdivision. The houses will be taller and closer together, he says, fronted by porches instead of garage doors, and the streets will be narrow and set in a grid pattern -- like a larger, less expensive version of Howell's Kinney Court. Because Mitchell's site adjoins one of the city's destination parks, his project qualifies for a packet of Smart Growth incentives, including waived utility fees, accelerated reimbursements for new infrastructure, and sidewalks and traffic signals. The community will be connected to walking trails that loop through the surrounding parkland. All told, the city has promised to invest about $5 million in the Milburn project, though city staff say that about $2.2 million of that total is for water and electric lines the city would buy back anyway. Mitchell says those incentives don't have a large cost impact on his development, perhaps erasing about $3,000 from the price of each home. But then again, he adds, when the profit margin on a $100,000 home is between $3,000-$8,000, it does help reduce the risk factor.

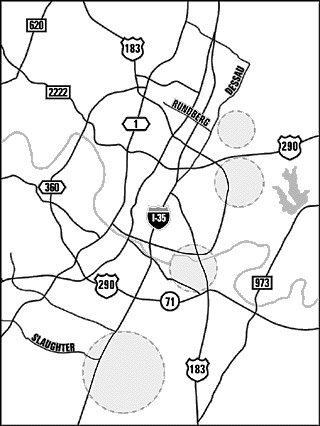

The project may be risky -- if for no other reason than its dependence on three developers who must maintain a cooperative relationship while working out shared operating costs, timetables, and compatibility. But if it works, says city special projects director Tracy Watson, co-author of Austin's TND ordinance, then we could see several more like it, bringing hundreds of new homes into the city limits. The city has already identified three more TND/destination park zones (see map), says Watson, one of which -- the one in South Austin -- is almost ready to be developed. "If these projects go like they think they will -- and like I think they will -- that's going to make an awful lot of people start taking a hard look at that, because people think of the TND as sort of a niche market, but I think that niche is real big." The Milburn project, Watson says, is an alternative for folks who want to know their neighbors rather than settle into the quarter-acre lifestyle. "They're not looking for the isolation of a standard suburb anymore; they want action," Watson says.

Mitchell says his company has chosen to break the mold not because current suburban development is less profitable or more expensive -- quite the contrary -- but because Milburn is looking for ways to keep its lower-end home market viable for the long term. "The value of a home is tied to the strength of its community," he says. "If the community fails, then homes decline in value, regardless of the style."

Mitchell is, of course, alluding to the standard cycle, in which clusters of cheap homes quickly degenerate into slums. Think of subdivisions like those surrounding East Stassney Lane in the Dove Springs area: shoddily built houses strafed with wide, dangerous streets, miles from the nearest high school or major employer, disconnected from any major corridors save I-35. Homeowners fled Dove Springs years ago; today, teens skipping school mill through the parking lots of convenience stores or work at the nearby Sonic, and the area is riddled with crime.

This is what the private market typically provides: low- to moderate-income families -- a ticket to blight, decay, and social isolation. In the long term, Mitchell says, that doesn't encourage homebuying in inner-city zones where housing could be done most efficiently.

Rentals Out of Reach

But it has to be mentioned that even the least expensive homes being offered in the Milburn project aren't within the reach of a huge slice of Austin's population. Nor will rental units in the project -- which will start at $600 for a one-bedroom apartment -- provide much relief for wage-earners. By its very nature, a TND is not designed to be an affordable housing initiative -- it's a way for developers to bend the rules to get more density and mixed use. Moreover, it's just coincidence that the first TND in our city happens to be from a builder who specializes in moderately priced homes; Watson says subsequent TNDs may well reach toward the upper end of the market.

To date, city initiatives aimed at increasing the housing stock have been targeted primarily at the good old single-family home. Partly, that's because neighborhoods tend to be friendlier toward low-cost houses than toward low-rent apartments. But it's also because the city has scant money to spend on housing programs, and those dollars flow a lot wider when they don't have to run as deep. It takes far less money to help a family earning $40,000 -- about 80% of the median income -- get over the hump from a cramped apartment into home ownership than it does to finance the construction of an apartment complex with reduced rents for folks earning $25,000. Yet people earning below $25,000, about half of the median income, comprise nearly a third of the metropolitan population, and wage-earners making less than $15,000 are the fastest-growing demographic.

Source: 1997 Hay Austin Survey, city of Austin, NLIHC, and Milburn Homes

Relatively little help has been available for the rent-strapped, save the occasional complex built through the state's tax-credit housing program, which adds a few hundred apartments per year within the city limits.

But there's been a swirl of activity lately over at the city's primary distribution outlet for housing assistance, the office of Neighborhood Housing and Community Development, and especially within the Austin Housing Finance Corporation, which NHCD staffs. Bundles of initiatives have been put together that officials hope will rekindle developers' interest in the urban core. Some of those have already been trotted out, most notably the SMART housing program, an outgrowth of the heralded Smart Growth plan that offers fee waivers and other benefits to projects located in the Desired Development Zone, situated predominately east of MoPac. And after drifting aimlessly for years, the AHFC has finally been put under the leadership of a real executive director (see "Dusting Away the Cobwebs," below).

There have been some changes in the parlance used in NHCD meeting rooms, too. "Subsidize," for example, has become a naughty word, and been replaced by the more potent-sounding "leverage." To subsidize is to commit the city's miniscule pot of federal block grants -- about $12 million -- to projects that serve only a few individuals and give no money back. In the past, the city has spent most of that money aiding existing homeowners too poor to repair their leaky roofs or crumbling foundations.

To leverage, in contrast, is to take those same funds and underwrite bank loans that will fix a lot more homes, albeit at some cost to the homeowner. Leveraging also means buying down mortgages for new homebuyers, purchasing and developing lots for low-cost homes, and issuing tax-exempt bonds through the AHFC that help finance new rental projects and repair older ones.

In short, this is the private/public partnership stuff that has been such a hit downtown, where the city tries to get the folks with the real money to help solve its problems. Housing advocates say, however, that the private market lever doesn't reach far enough to lift the rent burden off the city's poorest citizens. Only a constant, committed, and sweaty hammering -- and yes, by that they mean an exertion of city funds -- will chip away that rock, they say. The rental market is the most difficult piece of the housing continuum, the one where the biggest gap exists between what people need and what they can afford.

John Henneberger, of the Texas Low Income Housing Information Service, says the city is substituting phony "magic bullets" from the private sector for real leadership on the housing front. The $1 million housing trust fund established last year is typical, Henneberger says, of the city's empty symbolic gestures -- an example of stirring the pot but putting nothing inside. Henneberger's organization favors more outright purchases of rent-capped properties, and $1 million won't even stand up one wall of a new apartment complex. "The attention has got to get off of the trust fund," he says. "The trust fund has been a terrible distraction."

While that may seem to be a party-pooper attitude, the question Henneberger and others ask really hasn't been answered, in real dollar terms, by private-sector initiatives: How serious is the city about keeping working-class citizens within its borders? Local nonprofits that focus on low-cost housing development say that in the current Austin market, the financial options extended by lenders are no longer sufficient to plug the gap between income levels and the price of housing.

Walter Moreau, of the Central Texas Mutual Housing Association (CTHMA), says the city has been willing to sink hundreds of millions of dollars into watershed and roadways, but hasn't yet grasped the size of the capital investment needed to tackle housing. CTMHA has a 160-unit complex planned in Oak Hill, which will be reserved for renters earning under $35,000, and will likely be one of the first recipients of city housing trust fund money. Yet even with that $500,000 gift, Moreau says, plus discounted financing from seven different sources, CTMHA is having to defer its developer fee and kick in a half-million dollars of its own money to get the $14 million project up. That's because the rents that lower-income people can afford don't quickly pay off the high cost of development, Moreau says.

No matter how big a pot of loans the city captures with its million dollars of public equity, Moreau says, the impact on affordability is still only $1 million. Noting that AHFC is gearing up to issue $35-$40 million in tax-free bonds next year to finance housing, Moreau says that even the reduced interest rate available through bonds won't be cheap enough to build rental properties his target population could afford. "It sounds good to say we're going to lend the money and get the money back some day. But ... the rents would have to be higher to get that money back," says Moreau.

Likewise, the Guadalupe Neighborhood Development Corporation is faced with a widening gap between the size of the loans people are eligible to receive and the purchase price of their houses. This year, GNDC has applied for federal funds through the city, requesting as much as $50,000 per home purchase to help buyers get into homes, says project director Mark Rogers. A family at 50% of Austin's median family income, about $25,000, can qualify for a mortgage of about $40,000, says Rogers -- not even half of what it costs GNDC to produce a house nowadays. "The city has to realize that the upwardly mobile are swarming in here," says Rogers. "We've got to look at ... subsidies for low-to moderate-income people." Rogers suggests that the city follow the lead of cities in other states that provide bonus incentives to developers who include lower-cost units in their developments.

Moreau estimates it would take a trust fund of around $20 to $30 million to begin addressing the city's housing needs. Obviously, that kind of money won't come from the city. Moreau says it's time for nonprofits like his to begin recruiting private donors instead. "We can raise money for the opera and for the children's museum; can we raise $5 million to build a new affordable housing community?" says Moreau. "We would name an apartment complex for any wealthy donor who would consider donating $5 million."

Halpin of American Youth Works says that partnerships with private institutions, combined with innovative technologies for building homes more cheaply, is the only way to rapidly expand housing opportunities for lower-income residents. Others point out that private sector initiatives are fine, as long as we don't expect them to complete the picture.

Transitional housing for homeless persons, for example, is in critically short supply, says Kathy Ridings, director of social services for the local office of the Salvation Army. More and more two-parent families are coming to the Salvation Army shelter on Seventh Street, she says, often after shacking up with other families or living in cars. The shelter used to have a maximum stay of 30 days, but had to increase that to 90 days because families can often find nowhere else to go. It can takes months of sitting on waiting lists before apartments they can afford open up. "It is saying something about our city when two adults living together can't scrape up enough income to stay housed," Ridings says.

Through a charitable program known as Passages that helps homeless people regroup and find a place to live, most shelter recipients do move out eventually. But Julian Huerta, resident services director for Central Texas Mutual Housing, says a family that recently moved into one of his units had waited seven months for a home, even though the father was working. And once families in similar situations recover and decide to move out of rental housing, Huerta says, they typically move to Manor, Pflugerville, or Kyle.

Which is a reminder to Austin officials, as if any were needed, that no matter what the city does to address its housing needs, "affordable housing" is being built all around us, on rural hillsides in Del Valle, where two-lane roads opening onto Hwy. 71 back up with traffic jams at morning rush hour. How much will it cost to provide mass transit and health services out there when those houses turn into communities of indigents? Meanwhile, many East Austin neighborhoods continue to stagnate, producing high numbers of dropouts and kids who don't go to college. The costs of racial and economic segregation are enormous, and housing policy is one of the most direct, yet unfortunately most avoided, ways to deal with it. Will we at least commit to low-cost housing in the Mueller Airport redevelopment?

The good news is, our city is taking some steps to reverse its shortsighted policies. It remains to be seen, however, whether Austin has the will to place housing on the same planning stage as our other major issues, setting a course for a true integration of our rich and poor residents. ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.

A note to readers: Bold and uncensored, The Austin Chronicle has been Austin’s independent news source for over 40 years, expressing the community’s political and environmental concerns and supporting its active cultural scene. Now more than ever, we need your support to continue supplying Austin with independent, free press. If real news is important to you, please consider making a donation of $5, $10 or whatever you can afford, to help keep our journalism on stands.

April 6, 2001

Austin Housing Finance Corp., Walter Moreau, Paul Hilgers, Bill Howell, Richard Halpin, American Youth Works, TraditionalNeighborhood Developments, Matt Powell, TND, Affordable housing