Money to Burn

Cornyn Butts in on Tobacco Case

By Robert Bryce, Fri., Oct. 22, 1999

There's nothing like a few billion dollars to bring out the worst in people. Just look at the ongoing fight over legal fees for the lawyers who represented Texas in the tobacco lawsuit. Indeed, three or more of the seven deadly sins are represented. Filling the role of gluttony are the Big Five tobacco lawyers who want to collect between $2.3 billion and $3.3 billion for their two years' worth of work in the tobacco case. Representing pride -- or maybe it's envy -- is Texas Attorney General John Cornyn, who is waging a political war in an effort to make sure the tobacco lawyers get only a fraction of the billions they are after.

Finally, representing sloth is former attorney general Dan Morales, who allegedly backdated a contract in an effort to reward his lawyer pal, Marc Murr (see "My Friend Murr," below).

On the surface, this dispute should be simple: the five lawyers -- Walter Umphrey, Wayne Reaud, John O'Quinn, John Eddie Williams Jr., and Harold Nix -- won the lawsuit, so they should get paid for their efforts. They had a contingency fee contract that promised them a portion of the loot if the state won. And that's their strongest argument: A deal is a deal. They argue that they took a case with poor prospects, risked between $40 million and $50 million of their own money, and helped win the largest settlement in the history of civil litigation -- some $17.3 billion.

Still, $3.3 billion split five ways is an enormous amount of money. And these attorneys are not a very sympathetic bunch. As one Austin lawyer puts it, "They are cutthroat bloodsucking sons of bitches. They are not a pack of folks that you would ever give a shit about, quite frankly."

All probably true. But they know how to fight in court, winning a case no one ever thought they'd win. Now they're essentially holding the state hostage to make sure they get paid. They have begun collecting the first installments on the $3.3 billion awarded by a national arbitration panel, all of which will be paid directly by the tobacco companies. But the legal team hasn't relinquished its claim to the 15% share of the state's settlement. That $2.3 billion would come out of the state's award, granted to them by U.S. District Judge David Folsom, who is overseeing the tobacco case from his federal bench in Texarkana.

From one perspective, Cornyn's job could be simple: He could laud his fellow lawyers for their work, remind Texans that no one had ever beaten the tobacco companies in court, and revel in the state's windfall.

But Cornyn believes there is something fishy about the contract the Big Five made with Morales and the state. To his credit, Cornyn and his deputies have uncovered evidence that Morales doctored a contract, a move that could have netted his friend, Murr, several hundred million dollars. Cornyn thinks the Big Five may have also been involved in something nefarious.

And according to documents provided to the Chronicle by the attorney general's office, Cornyn has been subpoenaed to testify before a grand jury that is allegedly investigating the matter. Additionally, in a letter regarding an open records request filed by the Chronicle, Cornyn's office says there are "two ongoing federal investigations into the hiring of outside counsel by the Morales Administration." The letter goes on to say that the AG's office has shared information with the FBI and that both the FBI and the U.S. Attorney have "verbally requested that we do not disclose any information relevant to this investigation, as release at this time would interfere with prosecution of their case. Prosecution is pending."

Cornyn Pushes Ahead

But rather than wait for the feds and the grand jury to do their work, Cornyn is pressing his own investigation, albeit in a clumsy manner. On Oct. 5, Cornyn filed a writ of mandamus with the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in an effort to force Judge Folsom to rule on the motions in his court. While it's unclear if the mandamus will succeed, Cornyn has undoubtedly irritated Folsom. Why? In May, attorneys for the AG's office and the Big Five met with Folsom and agreed there was nothing for Folsom to rule on because both sides had reached a "standstill agreement" while they tried to mediate their dispute. But by the time the two sides met again in Folsom's court in August, Cornyn was clearly impatient, requesting the judge to take action.

Cornyn may have further insulted Folsom by insisting that he doesn't want to investigate the Big Five under Folsom's supervision, even though the federal judge has overseen all other aspects of this tobacco case. Instead, Cornyn wants to conduct his investigation under the Texas Supreme Court, which just happens to be all Republican, and of which Cornyn is a former justice.

While Folsom considers the attorney general's request to move the investigation to state court, Cornyn has made at least one other questionable move:

In August, he sent out 18 civil investigative demands -- or CIDs, the AG's equivalent of a subpoena -- to some of the lawyers who worked for Morales at the AG's office, and to other lawyers who have either worked with the Big Five or were recruited to work on the tobacco case. The demands seek all kinds of information from the attorneys, including documents that are clearly covered under attorney-client privilege.

It's a move that could be viewed as harassment because Cornyn issued the demands under the authority of the state's deceptive trade practices law, even though the statute is not applicable to professional service contracts such as those used by lawyers. Nor is the law applicable to contracts valued at more than $100,000. The issuance of the CIDs make it appear that Cornyn is more interested in ideology than anything else.

And, as the trial lawyers are all too happy to point out, Cornyn's biggest financial backers during his run for the AG's office were the tort reformers. About $1 million -- approximately 16% of the $6.5 million Cornyn spent during his campaign for AG -- came from Texans for Lawsuit Reform or from individuals who have contributed to the tort reform group. The tort reformers would like nothing better than to hurt the trial lawyers any way they can.

As it happens, the Big Five are big contributors to the Democrats. If Cornyn and Gov. George W. Bush can choke off some of the money the Big Five normally give to the Democrats, it should be easier for the GOP to keep its stranglehold on statewide offices while dealing with redistricting in the next legislative session. Indeed, some of Cornyn's critics insist that the only reason the attorney general is waging this battle is to stop the flow of money to the Democrats. For that reason, says one lawyer close to the case, "Cornyn will never settle this case. He's going to fight the trial lawyers until somebody dies of old age."

Then there's Morales, who, sources say, backdated a contract for Murr that could have netted Murr more than $500 million even though Murr's duties in the tobacco case were never clear to any of the Big Five's legal team.

In addition to the ongoing federal investigation into his deal with Murr, a look at the record shows that Morales clearly misled the public. Right after the $17 billion settlement was announced, Morales told reporters there was no way the outside counsel would get $2 billion in legal fees. At about the same time he was making that statement, Morales was signing a court document saying he wouldn't fight the Big Five's fee request. How's that for veracity?

So don't look for any heroes here. Instead, there's a gaggle of superstar lawyers armed with yet more superstar lawyers, all arguing over who gets to share in the multibillion-dollar fee jackpot. It's a fight with enough intrigue, subplots, and legal jargon to make Perry Mason wince. While other states are happily taking the tobacco money and moving on, Cornyn, Bush, and the handful of legislators who are attacking the Big Five for their fees are taking a lonely road. The politicos are fighting the lawyers even though by comparison, the Texas lawyers got less -- on a percentage basis -- than barristers in the other lead states.

The Big Five aren't exactly getting stiffed: Cornyn's office estimates they've already collected $364 million from the fees awarded to them by the arbitration panel. But lawyers elsewhere are reaping more. In Mississippi, the trial lawyers got 35% of the state's settlement, or about $1.4 billion. In Florida, the lawyers picked up $3.4 billion, 26% of the state's take. Here in Texas, even if the lawyers get the maximum they're asking for, they stand to take home about 19% of the state's total award, or $3.3 billion spread out over two decades.

The Long, Winding Road

While Cornyn is using his office as a bully pulpit to attack the Big Five, the lawyers have responded by hiring Michael Tigar, a former UT law professor and superstar litigator who has worked on a series of high-profile cases. While Tigar presses their case in court, Austin political consultant George Shipley, aka "Dr. Dirt," is putting the Big Five's spin on the press corps.

The case seems to have taken on a life of its own, what with the multitude of players and spin jobs in this complex story. Here's how it began:

Houston lawyer John O'Quinn didn't need any more lawsuits. And he certainly wasn't hurting for money. But when Morales called in late 1995 to see if O'Quinn was interested in working on the tobacco case, O'Quinn couldn't resist. The case held all his favorite elements: politics, intrigue, and of course, tons of money. A veteran of numerous high-profile tort cases, including the breast implant litigation, O'Quinn is one of the most famous lawyers in Texas. He's also one of the most hated. He's been sued several times by former business associates, and Fortune magazine once called him the "lawyer from hell."

It wasn't that Morales liked O'Quinn. In fact, O'Quinn gave money to one of Morales' opponents. But O'Quinn and the other four lawyers had the deep pockets that Morales needed. Morales, the Harvard graduate and first Hispanic elected to statewide office in Texas, simply didn't have the budget and manpower to go after the tobacco companies by himself. And that fact led to repeated attacks from Cornyn, who at the time was a candidate for Morales' job.

In November 1997, Cornyn lambasted Morales for hiring the Big Five, pointing out that the AG had a $250 million budget and 3,800 employees. "Can't Morales find a lawyer in his own office to represent the state in court without resorting to this offensive practice?" Cornyn asked.

The answer to Cornyn's question was clear. It was no. The Big Five spent between $40 million and $50 million litigating the case. That's about a fifth of the AG's entire annual budget. There was no way Morales could have risked that much money on a case with such poor prospects. Indeed, the odds were terrible. Between 1954 and 1996, between 800 and 1,000 personal injury lawsuits were filed against the tobacco companies. The plaintiffs lost every one. Why? The tobacco companies had nearly limitless resources. In May 1998, American Lawyer reported that in 1996, Big Tobacco's annual legal bill came to about $600 million. In 1997, it was estimated at $750 million. By the time this case settled in 1998, Big Tobacco had hired some 23 law firms in Texas alone.

Despite the odds, O'Quinn and the others agreed to work for the state. They liked Morales' strategy. Other states were suing solely for reimbursement of Medicaid costs incurred while treating smokers. Morales and the Big Five sued for Medicaid funds, too, but they also followed Florida's lead and sued the tobacco companies under the Racketeering and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act, a move that could have allowed the state to recover treble damages, and also exposed the companies to criminal penalties.

On March 29, 1996, Morales filed suit in federal court in Texarkana. In doing so, Texas became the seventh state to sue the cigarette makers. The Texas team asked for $4 billion and secretly hoped that they'd get $1 billion.

In announcing the suit, Morales said the Big Five would get 15% of any award. At the time, Governor Bush and everyone else ignored the matter. No one gave them a chance.

Over the next few months, however, the Big Five began earning their pay. They rented a facility in Texarkana and began preparing for a trial they believed would last six months. Everything about the case was Texas-sized. There were 129 attorneys of record in the case, and they filed 1,856 docket entries. There were 50,000 exhibits, 1,500 witnesses, and some 23 million documents that were coded, filed, and computerized.

During the first few months of the lawsuit, the tobacco companies made it clear they would fight the Texas case as long and as hard as they could. At one point, they even asked for all of the medical records for every Medicaid patient in Texas, a request that could have taken years to fulfill. The Big Five fought the tobacco companies on every motion, every request. They held several mock trials, presenting their evidence to Texarkana residents to gauge their reactions to the various arguments they planned to present. They also began honing their attacks under the RICO statute, which allowed them to use statistical models to prove damages and causation -- things they could not have done in an ordinary personal injury-type claim.

The RICO claim put the tobacco companies on their heels from the beginning. The RICO statute prevented the companies from presenting their usual defenses. It also allowed the state to subpoena all of the top tobacco executives. By the end of 1997, faced with putting their chief executives on the stand, and a protracted trial that they were likely to lose, the tobacco companies came to the bargaining table.

The Settlement On Jan. 16, 1998, Dan Morales was on top of the world. He announced that the tobacco companies had agreed to pay the state between $14.5 billion and $15 billion. Since then, the value of the settlement has been revised upward to $17.3 billion. And that's not all. Depending on who is doing the math, the final value of the deal could be up to $105 billion over 50 years, because the payments continue for as long as the tobacco companies sell cigarettes. In addition, there's a cost of living adjustment in each annual payment, and the state will likely have lower health care costs because it will have fewer smokers to care for.

No sooner had Morales announced the deal, however, than he was peppered with questions about the fees that would be paid to the Big Five. "I think any discussion or speculation of fees in the multibillion-dollar amount range is laughable," Morales told reporters. "I think the court is going to do something appropriate, something responsible." Unfortunately for Morales, the Big Five were not being so generous. Umphrey said that they were going to ask Folsom to "honor our contract." Asked if that meant getting the full 15%, Umphrey assured everyone that that was exactly what he meant.

Six days later, Folsom signed an order obligating Texas to pay $2.3 billion of its recovery to the Big Five.

Responding to the announcement of the settlement, Bush congratulated Morales and then quickly began complaining that the fees due the Big Five were "too big, way too big. A substantial part of that money ought to be going to the taxpayers." A group of legislators agreed with Bush and asked to intervene in the case to block payment of the fees to the lawyers. Cornyn joined in, saying that as AG he would not give any cases to lawyers whose "idea of public service is a fee that would make Midas blush."

Throughout 1998, the two sides skirmished about the fees. After months of wrangling, the Big Five agreed to submit their claims to a national arbitration panel. On Dec.11, the panel decided how much the lawyers from Florida, Mississippi, and Texas would get. The Big Five got $3.3 billion -- all of which would be paid by the tobacco companies. Not a penny would come from the state. But there was a catch. The tobacco companies agreed to pay no more than $500 million per year for all of the lawyers who worked on the tobacco lawsuits.

The $500 million per year will not be adjusted for inflation, and it must be shared with scores of lawyers from other states. So the Big Five will get their $3.3 billion, but the payments can be spread out over a period of 10 to 25 years, a fact that dramatically reduces the present-day value of the money.

New AG on the Block

Once he took office, Cornyn wasted little time addressing the fee dispute. On Jan. 12, representatives from Cornyn's office met with representatives of the Big Five to talk about the fee dispute and how to facilitate whatever investigation Cornyn wanted to conduct into their actions. The meeting was scheduled to start at 3:30pm but didn't actually get underway until about 4pm. The time is important because, during the meeting, Cornyn had a press release sent out saying that the Big Five "are not satisfied with their $3.3 billion attorneys fee award. They want a release from me, on behalf of the state, for any illegal or unethical conduct that they may have engaged in while representing the state." The fax machine time stamp on the press release is 4:21pm.

The Big Five attorneys were livid, feeling that Cornyn purposely stabbed them in the back. Charles Silver, a UT law professor who is an unpaid ethics advisor to the Big Five, was at the Jan. 12 meeting. After reading the press release, he wrote an op-ed piece that appeared in Texas Lawyer, blasting Cornyn. "An ethics investigation should not begin with a lie," wrote Silver, "but here in Texas one just did."

Seeing that Cornyn wanted to investigate their activities, the Big Five tried to strike a deal. They would relinquish their claim to the $2.3 billion award granted to them by Folsom if Cornyn agreed to conduct his investigation under the direction of Folsom's court. In return, the Big Five would only have claim to the $3.3 billion awarded by the arbitration panel. Cornyn refused.

Instead, while continuing his investigation, Cornyn is pursuing two legal arguments against the Big Five. First, he says that by retaining their claim to the $2.3 billion, the tobacco lawyers are essentially suing the state, a move that violates the 11th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which guarantees the states sovereign immunity. That immunity, Cornyn argues, means the fee dispute is a state matter and must be moved from federal court to the Texas Supreme Court. The Big Five insist that the fee fight is part of the original tobacco lawsuit and therefore should stay in Folsom's court. They've also said they will agree to comply with Cornyn's investigation if he will do it under Folsom's direction. Cornyn has refused.

Cornyn points out that the Big Five haven't given up their claim to the $2.3 billion awarded to them by Folsom. The lawyers were supposed to choose between the national arbitration panel's award of $3.3 billion, or stick with the $2.3 billion. Under the terms of the arbitration panel, they had until Dec. 31, 1998, to make their decision. They never did. Instead, they asked the court for more time to consider the matter, and they've used their claim on both pots of money in an effort to force Cornyn to call off his investigation. On Aug. 11, Cornyn's first assistant AG, Andy Taylor, told Folsom that the Big Five "have the gun to our head right now on their claim for dollars against the state." Taylor insists that the Big Five have to relinquish their claim on the $2.3 billion before there will be any progress in the case.

Cornyn and the private attorneys who represent the legislators, Pieter Schenkkan and Mike McKetta, are also arguing that the Big Five -- by asking for such exorbitant fees -- have breached their fiduciary duty to their client, the state. And because they have breached their duty, they should forfeit their fees. To bolster their case, the AG and Schenkkan point to a recent Texas Supreme Court case -- Burrow v. Arce -- in which the court ruled that the lawyers who were working on a contingency fee case could be denied their fees if they breached their fiduciary duty to their clients. But Cornyn has a problem: The Burrow case is in state court. He's fighting the Big Five in federal court. So on Oct. 5, Cornyn submitted his bid for mandamus to the Fifth Circuit, asking them to order Folsom to either dismiss the Big Five's $2.3 billion award or transfer the entire fee dispute to the Texas high court.

What's Cornyn's Angle?

The motivation of the Big Five is easily figured out: It's greed. Figuring out Cornyn's motivation isn't nearly so easy. To his critics, the motivation is all about money. They believe Cornyn is simply trying to prevent the Big Five from getting their multibillion-dollar payday because he and other members of the GOP believe -- rightly so -- that the Big Five will then make huge contributions to the Democrats. And now that the GOP has gained the advantage in Texas, Cornyn and other Republicans, including Cornyn and Bush's chief political strategist, Karl Rove, want to make sure they keep it. The best way to keep that edge, goes the theory, is to prevent the Big Five from collecting their billions in fees.

To bolster their point, they say there is no reason for Cornyn to fight the Big Five's fees because under the national arbitration award, the fees are paid by the tobacco companies, not the state. Even if he wins his fight with the Big Five, Cornyn won't win a dime for the state. Why? The tobacco companies have made it clear that none of the $500 million per year they've agreed to pay will go into state coffers. Therefore, there's no reason for Cornyn to fight it.

As for Rove, his background as a five-year consultant for tobacco giant Philip Morris Cos. Inc., raises suspicion in the eyes of critics. Perhaps, say Cornyn's detractors, Rove is whispering in Cornyn's ear and letting him know that now is the time to take the tort reform battle to the federal level. In fighting the Big Five, Cornyn knows that he can appeal to Texas voters (in a possible run at the governor's office) while at the same time auditioning on the national stage for a spot in the Bush White House. Or perhaps Rove and Cornyn see it as payback time. Now that the Big Five and other tort lawyers have hammered them in court, the tobacco companies are simply taking this chance to hammer the tort lawyers in the court of public opinion. And Cornyn, with his broad powers as attorney general, is doing that while assuring himself of future campaign funds from the tobacco companies.

Blakey, who was part of the Big Five's legal team, believes the fee fight is about Cornyn's efforts to protect Big Business. He and others point out that as a lawyer, Cornyn made his living defending big companies against plaintiffs' lawyers. Cornyn even made an appearance during the last few weeks of the 1998 campaign on behalf of Pittsburgh-Corning to argue against the right of out-of-state plaintiffs to file suit in Texas on claims related to asbestos.

Cornyn, says Blakey, is simply fighting the trial lawyers in an effort to protect the moneyed class. "This is a cultural war between people who want to hold people with money responsible for what they do, and the people with money who want to be free of responsibility for what they do," says Blakey.

Perhaps that is true. But Cornyn also appears to be fighting for Libertarian/Republican ideology about governmental power and lawyers-for-hire. Cornyn and the legislators who are led by Sen. Troy Fraser, a Republican from Horseshoe Bay whose 1996 campaign was financed largely by tort reformers, claim that only the Texas Legislature has the power to make contingency fee contracts with lawyers.

The other part of their argument is that Morales and the other attorneys general should never have made deals with the private lawyers. By doing so, they abdicated too much state power to private citizens. "We can't have private lawyers enforcing public law, where the state is a party to litigation and then have the lawyers get an incentive kicker for damages," says Robert A. Levy, a senior fellow in constitutional studies at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank in Washington, D.C. "The state is the sole entity that wields coercive power. We cannot give that power over to private attorneys, much less tell them that they will get more money if you are tougher on a defendant. That would be like having a district attorney who gets a higher salary if he gets the death penalty for a defendant instead of life in prison."

Whatever the ideology behind his involvement, sources close to Cornyn say the AG has no choice but to continue fighting the Big Five as long as he can. That's particularly true now that the FBI is involved. If Cornyn settled the case now and the U.S. Attorney's office returns indictments against Morales, Murr, or anyone else, then Cornyn would look like an idiot, says the source. In addition, the source says that Cornyn has to fully investigate charges made by Houston tort lawyer Joe Jamail, who has allegedly told investigators that Morales asked him and other tort lawyers for a $1 million contribution to his legal defense fund.

Politics aside, there are some very troubling public policy aspects of the way Cornyn has handled the fee fight. For instance, Cornyn refused to answer any questions from the Chronicle about the investigation. Instead, he issued a four-paragraph statement that did not answer any of the 20 questions the Chronicle had submitted in writing (see "Cornyn Responds," below). His office also refused to disclose how many hours state attorneys have spent working on the tobacco litigation. In response to a request made by the Chronicle under the Texas Public Information Act, the AG's office refused to even estimate the number of hours spent on the matter, saying only that the office "is not required to create documents and no such documents exist."

There's plenty of irony here. Cornyn has demanded to see time sheets for the Big Five to determine how many hours they worked on the case. But now Cornyn is refusing to produce the same documents to the media. The other irony is that Cornyn is the state's chief open records officer. In fact, he gave a speech to the Freedom of Information Foundation of Texas on Oct. 9 in which he said that the importance "of a free media and the absolute necessity [his emphasis] of government to conduct its business in the open, these are, in my view, not adornments of the American way of life, but rather bedrock principles of a free society."

There are other actions which appear to violate the openness that Cornyn professes to support so avidly. None of the press statements issued by the AG's office that pertain to the tobacco fee fight have been posted on the AG's Web site. That includes the previously discussed Jan. 12 press statement and the Oct. 5 release announcing the writ of mandamus to the Fifth Circuit. If the tobacco fee fight is so important to Cornyn and Texas taxpayers, why haven't those documents been posted on the Internet so everyone can see them?

Other questions -- including ones about the legal basis for the issuance of the CIDs and Cornyn's refusal to conduct his investigation under Folsom -- remain unanswered. For the record, AG spokesman Ted Delisi would say only, "We don't want to disclose our legal strategy." Cornyn is even coming under fire from his most ardent supporters. This summer, the Dallas Morning News, a solid backer of the Bush regime and the Republican agenda, questioned Cornyn's strategy, saying that unless the Big Five tobacco lawyers have "some assurances that Mr. Cornyn's investigation is not a pretext for politically motivated trial lawyer bashing and lawsuit reform," then they won't back down and allow a settlement. "The battle is philosophical, political, perhaps even personal. Prudent, it isn't," said the News' editorial team.

So in the AG's view, do the Big Five deserve to get paid for their work? Pete Schenkken, who is working alongside Cornyn, refuses to say how much they should be paid. Instead he says, "They are due an appropriate fee, unless they breached their fiduciary duty." Beyond that, Schenkken, like everyone else on Cornyn's side, refuses to say anything for the record. Many aspects of the tobacco fight can be argued. But there is one indisputable fact: The tobacco settlement was a colossal win for the state of Texas. Without risking a dime of taxpayers' money, the state got an outlandish sum of money that will enrich Texas for generations to come. It also forced the tobacco companies to quit advertising on billboards, fund anti-smoking campaigns, and pay for hundreds of millions of dollars worth of medical research.

But now that the tort lawyers have won the war, Cornyn and Bush are only too happy to quarrel with them over the spoils of the fight. It's like the Anita Bryant stance on homosexuality: Love the sinner, hate the sin. In the tobacco fight, it appears that Cornyn and Bush love the money that the tort lawyers got out of the tobacco companies, but they hate the way they got it. And rather than disavow the money, they are disavowing the lawyers.

Cornyn has pledged to continue fighting this battle, perhaps all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. And the Big Five have about 3.3 billion reasons to keep the fight going. They've already pocketed more than $300 million, which is enough money to buy two or three more Michael Tigar-type barristers to make sure their voices get heard.

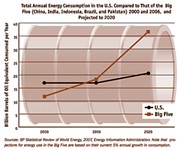

And while no clear winner has emerged in the fee fight, there is one clear winner overall, and believe it or not, it's the tobacco industry. The companies have settled the claims brought by the states, and have received a guarantee that the states and state medical institutions won't sue them again. They narrowly missed getting a national settlement that would have prevented future lawsuits against them. They have limited the amount of money they will have to pay the lawyers to $500 million per year, a figure that amounts to about two cents per pack of cigarettes sold. Armed with their state settlement agreements, the tobacco companies are assured of some future stability. Better still, they now have some leverage against the lawsuit the federal government filed against them Sept. 22.

The suit seeks recovery of some of the $20 billion spent by the federal government each year on smoking-related illnesses. But the tobacco companies now have an unlikely ally in their fight with the feds: the states, which have a financial interest in making sure the feds don't get a dime. After all, any money the feds squeeze out of the tobacco companies will likely come out of the money that the companies are currently paying the states.

All of those factors have led at least one of the lawyers who worked against the tobacco companies to wonder if it was all worth it. The sick twist in the fight, says the lawyer, is that "the tobacco companies made all the states that settled with them partners in the cigarette business. This enterprise that was so evil, the one that's killing our children, is now a partner of the states. Settling the lawsuits with the states is the smartest thing the tobacco companies ever did." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.