How Green Grows My County?

'Greenprints' aim to protect our most precious natural lands

By Katherine Gregor, Fri., Dec. 14, 2007

On an unseasonably warm and lovely November day, the kind that glorifies living in Central Texas, some 60 local dignitaries escaped their desk jobs to share a slow, relaxed raft trip along the winding bends of the Colorado River. The five-mile float showcased the 87-mile stretch of free-flowing river that begins at Longhorn Dam, just east of I-35, then twists and turns toward the southeast to the Bastrop County line. The Austin-Bastrop River Corridor Partnership and the Trust for Public Land organized the outing as advocacy outreach – to present the ecological, recreational, and economic features of the river and its corridor and discuss the impacts of growth, development, and change.

Yet instead of talking policy, the rafters succumbed to the river's simple charms. Life-vested governmental types like state Rep. Eddie Rodriguez, former Travis Co. Commissioner Valerie Bristol, Austin Water Utility's Daryl Slusher, and Bastrop Economic Development CEO Joe Newman chatted about the birds flying by (there's a scissor-tailed flycatcher!), the trees along the bank (numerous bald cypress), and the crystal clarity of the water. Everyone wanted to see and touch a week-old soft-shelled turtle. All bemoaned the handful of sand and gravel mines that abut the shore and the waterfront homeowners who'd removed natural forest fringe in favor of fertilized Saint Augustine lawns. More compellingly than any policy paper, the river provided its own best precept for conservation. What river-floater wouldn't rally to support a healthy riparian (waterway margin) ecosystem along its banks?

The Colorado River corridor also emerged as a star example in the 2006 Travis Co. Greenprint for Growth, a conservation planning initiative of the Trust for Public Land. As a blueprint is to a new building – a detailed depiction of what's envisioned – a "greenprint" is to new parks and conservation lands. The greenprinting process identifies high-priority areas to preserve – such as our nearly unspoiled river corridor – before they are lost to development. The term and the methodology were developed by TPL, a national nonprofit that conserves natural land for public enjoyment. The Travis Co. Greenprint for Growth is among the TPL's most detailed and large-scale greenprint projects to date. The final report was completed and publicly distributed this summer. But the mapping model already is influencing government and private action – for example, determining which creek-front and watershed tracts the city acquires with Proposition 2 bond money approved in 2006. TPL's James Sharp noted, "Austin Greenways and Destination Parks acquisitions [with Prop. 2 funds are] focusing on areas east of I-35" – the Eastside being the highest priority that emerged sharply in the greenprint. A resolution at City Council this week will protect Colorado River shoreline in eastern Travis County, to begin implementing the ABRCP vision.

Now, Envision Central Texas is partnering with TPL's Texas office to complete a five-county regional greenprint. That $250,000 project will identify and map high-priority lands for conservation in Williamson, Hays, Bastrop, and Caldwell counties, then merge all five county greenprints into one comprehensive regional vision. As triage tools to determine which specific tracts of land get protected with scarce conservation dollars, the greenprints will shape what future generations know of Central Texas' natural beauty and environment.

Mapping Priorities

The TPL has conducted greenprints in relatively few areas around the country. In Texas, the Trust has greenprinted West Galveston Island and the Armand Bayou watershed south of Houston; TPL and the North Central Texas Council of Governments have begun a broad-brush greenprint for a 16-county area around Dallas. Most are being done in fast-developing regions like Central Texas, where planning for "green infrastructure" is critical to balance rapid population growth. By 2025, the U.S. Census Bureau projects, Central Texas will have doubled its 2000 population. That presents some urgent challenges for regional land-use planning. "Determining where not to build is an integral part of deciding where to build," explains TPL advisory board member Sinclair Black.

"I wish I had had these guidelines sooner, but it is never too late to make commitments to building and expanding our parks infrastructure," stated Travis Co. Commissioner Margaret Gómez.

While a greenprint is prescriptive, it lacks the force of law. In Texas, counties have extremely limited land-use regulation powers – witness the parallel quandary over where to locate ugly necessities like landfills and sewage-treatment plants. Regional planning is so challenging because it requires interjurisdictional cooperation by cities, counties, private landowners, and other entities. It requires all kinds of people to sit down together, put aside their narrow self-interests, and agree on values, priorities, and a consensus plan of action. Therein lies the real power of the greenprint. The upfront stakeholder process brings together key players, who agree on a vision and specific priorities. That galvanizes public support, which translates into political will and action.

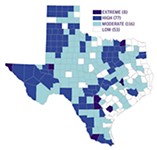

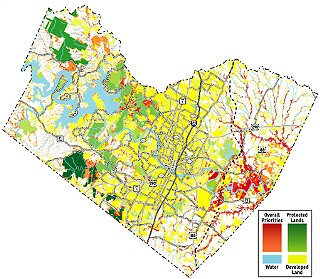

The graphic product – the greenprint model – identifies through color-coding the specific available tracts whose protection can best satisfy multiple community priorities. Land already protected is shown in green. Shown in urgent red are the parcels that would deliver the greatest bang for our limited land-acquisition bucks. Areas in orange have a moderate conservation priority. (See map) But a greenprint isn't just a land map in the usual sense; what it maps most uniquely are community priorities.

"The great success of the Travis Co. Greenprint project is that it brought citizens, community groups, and business leaders together to produce a roadmap," Mayor Will Wynn stated for the report. "The greenprint provides us with a vision for moving forward and allows us to collaborate to leverage our resources to everyone's benefit."

An intriguing yin-yang of greenprinting: It's both high tech and high touch.

The high tech component is Geographic Information System computer modeling. A digital update on cartography, GIS uses and analyzes voluminous data from multiple sources – geographic, spatial, satellite, you name it – to produce pinpoint-accurate maps. And GIS can produce not just maps but animations that document change over time – as in climate-change modeling – or that compare the effects of different variables. (The city of Austin has used GIS technology to create a new GIS parks viewer; it's also used by the city for neighborhood planning and zoning, utility management, and emergency services.) For the Greenprint for Growth, the Trust for Public Land used GIS modeling to create an inventory of all Travis Co. land. It documented existing conservation land and developed land, then analyzed still-available open land. GIS analysis identified the parcels that matched exacting specifications, based on community values. The static maps in TPL's Greenprint for Growth booklet only hint at the powers of GIS modeling; the cool tool is the interactive version (eventually to be online), which allows users to zoom in on specific parcels, conduct detailed analyses, and compare scenarios. Best of all, the greenprint models can be continually updated over time as new GIS data sets become available. That makes them a great long-term investment.

A Five-County Vision

In Travis County, the TPL facilitated the community input process between October 2005 and October 2006. (Backfill fundraising and final development and distribution of the report kept TPL busy until completion of the project in July.) If sufficient funds can be raised soon, a similar four-county community input process led by Envision Central Texas will begin in the first quarter of next year. TPL's Texas office was inspired to create a greenprint by the 2004 ECT "Vision for Central Texas." That regional vision – derived from the input of nearly 15,000 Central Texans, 150 community leaders, and a 73-member board – documented an ardent desire, in the face of rapid growth, to protect ecologically sensitive open land, as well as clean water and clean air. Also important to Central Texans was ensuring adequate recreational green space, including parks and trails, close to where people live. "Rather than simply reacting to growth and sprawl, or settling for what land is left after development occurs," stated ECT, "this vision advocates for proactively planning for a green infrastructure that is as important to our future as power lines, wastewater treatment facilities and roads."

TPL knew that a greenprint could help translate that broad vision into a prioritized conservation action plan and brought in as project partners Travis Co., the city of Austin, and the University of Texas School of Architecture. Some tension developed between TPL and ECT concerning whether the greenprint would address just Travis Co. That alone required fundraising $175,000, all TPL felt it could bite off initially. As a compromise to stave off regional mission-creep, ECT supported – but did not officially partner on – the Travis Co. greenprint.

Now ECT, TPL, and the Central Texas Council of Governments are seeking funding for the five-county version. Heading up the effort are Open Space Committee co-chairs Valerie Bristol (now director of external affairs for the Nature Conservancy of Texas) and Hays Co. Commissioner Karen Ford. "I hope that we can inspire the private sector to help, as I think it will benefit them every bit as much as the public sector," said Envision Central Texas Executive Director Sally Campbell. "Understanding the 'green bones' of the region will be essential so that developers can make their plans work in concert with the community's green space priorities."

ECT is anxiously awaiting word on a $115,000 greenprint grant from the Federal Highway Administration. Hays Co. commissioners have approved a $50,000 contribution to the project; smaller (and poorer) Bastrop and Caldwell have promised to do what they can. Williamson Co. commissioners are considering an ECT request for another $50,000. That urbanizing county is currently updating its park master plan; WilCo also is developing a comprehensive regional habitat conservation plan, with a $1 million grant from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and has established the Williamson Co. Conservation Foundation. A greenprint could affect decision-making in all five counties and in cities like Cedar Park, where last November voters approved nearly $18 million in bonds for parks and conservation.

Travis County Process

Courtesy of the Trust for Public Land

Stakeholder meetings for the Travis Co. Greenprint for Growth involved representatives from two dozen organizations, including the Real Estate Council of Austin, the Lower Colorado River Authority, the National Park Service, Capital Metro, the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department, as well as a roundup of the usual suspects for environmental action in Austin. The stakeholders generated a list of about 40 priorities, said project director Anjali Kaul. These were grouped into four overall criteria:

1) water quality/quantity protection,

2) recreational opportunities,

3) protection of sensitive/rare environmental features,

4) protection of cultural resources (e.g., agrarian land and scenic corridors).

The dialogue became heated at times, as single-issue participants lobbied for their own priorities – such as protecting water quality in the Hill Country or farmland preservation or Eastside parks equity. "There was honest disagreement on all sides about which priorities were most important," said Kaul. In the end, "the stakeholders decided to give each criteria equal weighting, to completely take the politics out of it." In the final model, each of the four criteria classes for conservation was weighted equally at 25%.

Within each class, a list of subcriteria also was weighted. For example, under recreational opportunities, park equity (for low-income areas) and floodplain areas were weighted respectively at 15% and 25% of the total. Green space, water access, adjacency to existing parks, and trail corridors each were weighted 10%; community gardens, trail connectivity, riparian corridors, and wildlife corridors each counted for 5%. TPL produced greenprint models for each of the four criteria individually. These then were blended into a master model showing overall conservation priorities. On the overall map, areas that bleed red generally rated as high priority on at least three individual criteria maps. That's the fundamental premise of greenprinting: With limited resources, conserve the land that achieves multiple values. Of course, individual greenprints also can be strategically used to acquire land that achieves a single conservation priority – such as protecting water quality.

At first glance, the overall conservation-priorities map may be surprising. What leaps out is the need and opportunity to conserve land on the Eastside. (In part, this is because substantial conservation already has occurred to the west in the Hill Country, Edwards Aquifer recharge zone, and Balcones Canyonlands.) The largest swath of high-priority red shows up in far eastern Travis Co., along the floodplains of the Colorado River and creeks. This land is environmentally sensitive, not yet developed, and not yet protected – the greenprint trifecta. Shaping this result: Floodplain land scored 25% under two criteria classes – water quality and recreational opportunities. Protecting the Colorado River corridor and its wide floodplain emerged as the single-largest east-county opportunity. TPL expects the Bastrop Co. greenprint also to prioritize the Colorado River as it winds southeast to the Bastrop Co. line, on it way toward the Gulf of Mexico.

Photo courtesy of the Trust for Public Land

The city's official Desired Development Zone is largely east of I-35 and along its corridor, in deference to the Drinking Water Protection Zone over the aquifer. The greenprint documents the need to reconsider this more carefully and protect Eastside land from development, as well. "The greenprint shows us where we need to focus on not growing," said ECT board member Cid Galindo, who is also a city Planning commissioner. "It can focus public attention on environmentally sensitive areas on the east side of the county. Conserving land there can head off future erosion and habitat problems." It also can improve parks equity for Eastside residents and prevent expensive city floodplain buyouts, such as those necessary along Onion Creek.

In Western Travis Co., a clear priority that emerged was land acquisition contiguous to the Balcones Canyonlands Preserve and the Balcones Canyonlands National Wildlife Refuge. Contiguous land is of particular value, for criteria such as wildlife habitat. Similarly, in the Southwest, the priority acquisitions targeted would link BCP and the water-quality-protection lands already acquired by the city. For the city of Austin's current bond-acquisition program, the Travis Co. greenprint is being used to identify high-priority green-way corridors and potential sites for larger regional parks, like Morrison Ranch. Within the central city, the Walnut Creek Watershed showed up as a high priority.

Wendy Scaperotta, a senior planner with Travis Co., reports, "Our first application of the greenprint process will be to identify specific parcels along eastern creeks that we want to target for acquisition." Travis Central Appraisal District information will be used to identify specific parcels to acquire – from willing sellers, of course. "Voters approved $62 million in 2005 for parkland acquisition and improvements, of which $15 million is earmarked for land acquisition along Onion and other eastern Travis County creeks," said Scaperotta. The county plans to update the greenprint model as new data becomes available, then use it to update its Parks and Natural Areas Master Plan and plan for future bond elections.

Making It Real

How will the greenprints actually translate into protected land? That's the $500 million question – $500 million being the estimated value of all 22,000 acres in Travis Co. tagged as high priority for conservation. Some land could be purchased outright; other tracts can be protected through conservation tools like easements, stewardship agreements, and landowner incentives for sustainable management, said TPL's Sharp. Engaged developers may also contribute land: The developer of Austin's Colony contributed land for the Colorado River park, for example, and developer Pete Dwyer has been using the greenprint to guide plans for tracts in East Austin. Sharp took care to note that the intent of "the analysis is not to identify private land for taking" but rather to prepare local governments "to work with landowners willing to sell or steward." (God forbid we should have any "takings" in Texas!) When it gets down to the brass tacks of how to conserve specific tracts from those willing landowners, the Trust for Public Land can bring to bear its 35 years of experience conserving more than 2.2 million acres nationwide – including more than 31,000 in Texas – said Texas office director Nan McRaven.

Next steps? Both McRaven and Jim Walker, incoming Envision Central Texas board president, said that the Travis Co. greenprint now needs to be translated into a detailed action plan – with specific projects, milestones, and assignments. As soon as resources allow, they hope to initiate an inclusive greenprint stewardship session; one model is the weeklong "stewardship exchange" conducted for Armand Bayou near Houston. While with Motorola, McRaven served as co-chair for the 1989-1992 Regional/Urban Design Assistance Team process, in which some 900 citizens and volunteers contributed to a vision for Downtown Austin; she also suggested as a model the three-day community-planning session, with hundreds of participants, that culminated in a council-endorsed call to action.

"We need to get really creative with the private sector and look into tools like transfer of development rights," said Walker. That includes being "very upfront and real about what developers and landowners will need from this – not being naive about it – to tackle the practical realities. This can be a catalyst in the evolution of how we think about conservation in Central Texas."

Galindo also cited transfer of development rights as an important approach to engage developers. The transfer is a legal tool (although not yet in Austin) by which developers can gain additional density in an identified "desired development zone"; in return, they forgo development of land in a defined environmentally sensitive area. The mitigation land feature adopted in the new Save Our Springs Ordinance amendment and proposals for a density-bonus program Downtown use the same basic concept.

Meanwhile, the work of the Austin-Bastrop River Corridor Partnership serves as a stellar example of the action that each "high priority" zone will need from all of us. The partnership began as a conversation among Colorado River agencies and neighbors in 2003; its mission is "to support sustainable development and a healthy riparian ... ecosystem." Already they've achieved enthusiastic cooperation from all the big players; planning workshops have been attended by a long and impressive list of organizations and individuals. In April, the partnership published "Discovering the Colorado: A Vision for the Austin-Bastrop River Corridor," printed by the Lower Colorado River Authority. (For a copy, e-mail [email protected].) This Thursday the Austin City Council considers a resolution to begin implementing that vision. Sponsor Brewster McCracken said establishing a Critical Water Quality Zone along the Colorado River shoreline, downstream of Lady Bird Lake (Longhorn Dam), is a tool to buffer the river from development. To protect the riparian zone, a minimum development setback of 200 to 400 feet will be required – newly measured from the edge of the river bank. This will force sand-and-gravel mining operations back from the river, within the city's five-mile ETJ (extra-territorial jurisdiction).

In May, ECT recognized the partnership and its vision report with a 2007 Community Stewardship Award. Thanks to the greenprint, the Trust for Public Land decided to partner with the Austin-Bastrop River Corridor Partnership as one of its major Texas conservation programs. Joint conservation goals include clean water, preserved wildlands, forested riversides, and well-designed public access and outlets for increased river-rafting, tubing, canoeing, and other recreational uses.

Like a drifting float down the Colorado itself, progress toward protecting the 87-mile corridor promises to continue slowly but steadily. In 2008, the partnership plans to conduct a February waterways workshop for Bastrop and Smithville, develop its own GIS database, conduct monthly river monitoring trips in both counties, and step up education and outreach efforts to raise awareness. Toward that end, members hope to create more community river festivals, like the educational NatureFest held in Bastrop Nov. 3. Achieving the vision will require many volunteers and partners to lean into their paddles, over many years, as with the overall greenprinting effort. But it bodes well for the region that collaborative conservation efforts keep rolling, rolling, rolling on the river.

For more info, or to become a Greenprint for Growth funding partner, contact the Texas office of the Trust for Public Land (www.tpl.org) or Envision Central Texas (www.envisioncentraltexas.org).

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.