Crime Month: Encyclopedia Brown

Can you solve our fondness for Idaville's favorite sleuth?

By Laura Jones, 11:59AM, Wed. Jul. 3, 2019

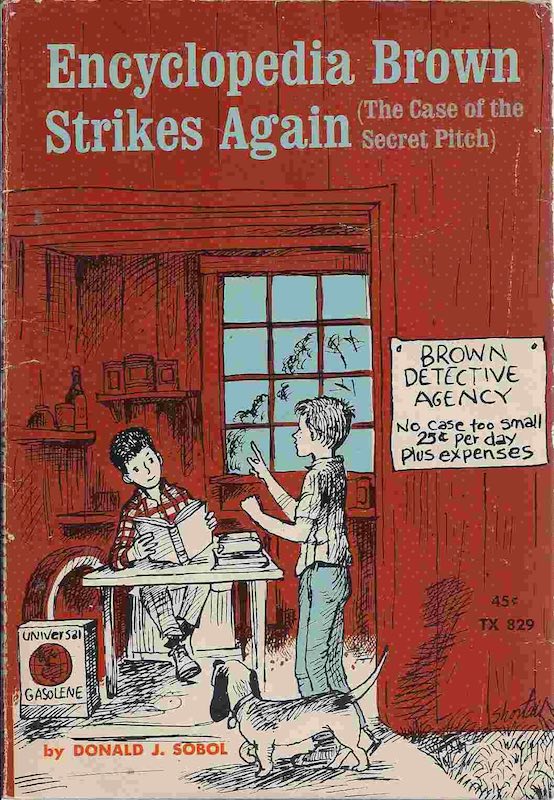

I’m no detective and here’s how I know. From the time I was 6 to 10, I spent every summer holed up with musty, dog-eared paperbacks checked out from the library of the Encyclopedia Brown series, written primarily by Donald J. Sobol, beginning in 1963.

I tried right along with the whiz kid to solve all the neighborhood mysteries that inevitably found their way to his door, either through his father, the eternally stumped investigator Chief Brown, or via EB’s own detective agency, where for a quarter he’d help a client crack a case.

Sobol’s brilliance was that he gave the reader the opportunity to figure out the crime, right along with his protagonist, Leroy aka “Encyclopedia” Brown. I never could. I was as hapless as old Chief Brown extolling his latest dilemma at dinner, and my frustration kept me coming back for more.

The formula for the series – which included titles like Encyclopedia Brown Keeps the Peace, Encyclopedia Brown Gets His Man, and my favorite, Encyclopedia Brown Solves Them All – was simple. Over a few pages, the fifth grader – and reader – would learn the details of some seemingly impregnable case. By the end, he figured it out easy as pie. But before the reveal, Sobel posed a simple italicized question at the bottom of the page. How did he do it? What was the answer? And then the directive: To find out, turn to page __.

Heart pounding, I’d race through every detail, attempting to guess the answer and prove myself as smart as the boy who had read “more books than anybody, and never forgot a word." The one who kept Idaville crook-free, because criminals knew better than to stir up trouble in that particular seaside town.

Turning to the back of the book, I’d once again discover I didn’t know the answer for why a simple clue had revealed an alibi’s flimsiness, or proved town bully Bugs Meany was the root of all evil. Encyclopedia Brown’s mind was laser-focused on details, but I was more of a dreamer, lost in Sobol’s small-town scenarios: the “two car washes, two delicatessens, three movie theaters, and four banks.”

There was – and is – a simple richness to the series’ language and characters that made the books inherently readable to a young child surrounded by real-life dangers overheard in the background on the six o’clock news. There was comfort in the books’ simplicity: family dinners, even sidewalks, and red brick houses with white picket fences. Encyclopedia Brown’s town was a world where a kid could set up a detective agency over his garage, use his brain, and make a quarter or two; it was safe, measured, and clean as his new red sneakers. The missing ring was always found, the falling woman always caught. The not-so-crafty culprit never eluded justice, no thanks to Idaville’s chief of police. Or me. It was thanks to the scrappy young detective who outpaced even the most devious minds, all while sipping his soup and acing like a fifth-grader.

A note to readers: Bold and uncensored, The Austin Chronicle has been Austin’s independent news source for over 40 years, expressing the community’s political and environmental concerns and supporting its active cultural scene. Now more than ever, we need your support to continue supplying Austin with independent, free press. If real news is important to you, please consider making a donation of $5, $10 or whatever you can afford, to help keep our journalism on stands.

Robert Faires, Aug. 1, 2019

Kimberley Jones, July 30, 2019

Feb. 28, 2020

Feb. 21, 2020

July Is Crime Month, Crime Month 2019, Encyclopedia Brown, Donald J. Sobol