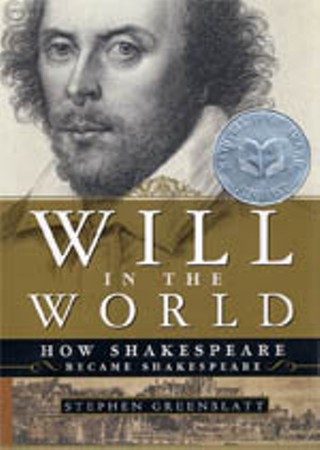

Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare

Stephen Greenblatt on 'Will in the World'

Reviewed by Robert Faires, Fri., Oct. 7, 2005

The shelves groan with biographies that attempt to show us the man behind the ever-astonishing works of Shakespeare, so many that you'd think there can't possibly be anything left to add. And yet, the publication of Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare proved that there's still room for new portraits of the Bard. Harvard professor Stephen Greenblatt renders an extraordinarily vivid image of the playwright right down to the blood and bone, making original, captivating connections between Shakespeare's art and life. The book was a finalist for the National Book Awards, the National Book Critics Circle awards, and the Pulitzer Prize, among others. In advance of his visit to Austin to deliver the Thomas Cranfill Shakespeare Lecture at UT, the Chronicle spoke with Greenblatt about his book and the UT lecture, titled "Shakespeare and the Ethics of Authority."

Austin Chronicle: Why did the world need another Shakespeare biography?

Stephen Greenblatt: It probably didn't need in any desperate way another Shakespeare biography, but I and other people who love Shakespeare have the desire to know who this person was. This is the greatest writer of the last thousand years and maybe the greatest writer of the last several thousand years in the Western world, and it's irresistible to want to know who this person is. Certainly, the world didn't need another biography of Shakespeare as an enumeration of the known facts about him. There aren't that many of them, and that task has been extremely well-done now since the late 19th century. The question is how do you get from those facts to any imaginable human being, any face that you could see.

AC: What keys helped you to open that door?

SG: First, you have to master what's out there. But having said that, as I say in the book, you have to use your imagination. For me, there were two versions of this impetus, one slightly more glamorous than the other. The less glamorous but practical thing is that when I was editing The Norton Shakespeare and writing the general introduction, I allowed myself to fantasize about what kind of situations in the childhood of such a person could have triggered some of the things that he did. What it was like as a little boy to watch his father get dressed as a mayor of Stratford – or for that matter just to watch his father get dressed, that moment when you realize that people wear costumes. Just trying to imagine, without any evidence behind it except that his father was mayor and we know there were processions. Long before writing a biography, I thought about this, even though academics aren't supposed to be allowed to do this. But one can have occasional transgressions.

And then, as I've said in interviews, I had these conversations with Marc Norman, who was writing a screenplay about Shakespeare and wanted to know what he should use from Shakespeare's life. I said, "Forget it. There's nothing in the life that's interesting. Make a movie about something else." But he went on with Tom Stoppard to write the screenplay for Shakespeare in Love. The point is not that the film is historically accurate, because it obviously isn't, but that the film is based on the supposition that it wasn't only what Shakespeare read when he sat in his study that enabled him to write what he did. If you want to figure out how Shakespeare got from being the person who wrote Two Gentlemen of Verona, which is a good sort of workmanlike play that he wrote at the beginning of his career, to being a few years later the author of Romeo and Juliet, you have to start thinking about what his relationship to life was.

AC: What will "Shakespeare and the Ethics of Authority" be about?

SG: My lecture will take off from a peculiar conversation I had with none other than William Jefferson Clinton. I went to a reception at the White House in 1998 that a friend of mine had organized because he was poet laureate at the time, and I had an amazing conversation with Clinton about Shakespeare and whether there's an ethically adequate object for immense ambition. So my talk will start by thinking about whether Shakespeare thought there was such a thing as ethical adequacy in human ambition, an object of ambition that would satisfy you, not simply your lust for power but your feeling for justice.

AC: Are there characters who come close, or are we always looking at failed ambition?

SG: I think that on the whole Shakespeare was skeptical about – I mean, Shakespeare had a lot of different accounts about why you'd wind up ruling a country, including the account that we currently have, which is you're the son of someone else who ruled the country. So that I think Shakespeare would have found the current order of things exceedingly familiar, and if we'd told him it was the result of an election, he would've said, [in a skeptical tone] "Uh huh." [Laughs] In that sense, I don't think he would have been surprised. He might have been more surprised at our belief, which I cherish, that there should be something other than a geneological proximity to someone else who held power.

The other thing, as I will say in my talk, is I think that he thought that ruling was a fantastic, grinding effort. The idea that you could spend a lot of time on vacation as a ruler would have astonished him. That you could work out and sleep well and generally have a good time that way, I think he would've been flabbergasted by. Because over and over he depicts rule as an enormous burden, and an emblem of the burdensomeness of it is sleeplessness. To that extent, the current situation would have amazed him.

Stephen Greenblatt will speak on "Shakespeare and the Ethics of Authority" Monday, Oct. 10, at 7pm, in Jessen Auditorium (Rainey Hall) on the UT campus. The lecture is free and open to the public.