Book Review: Readings

Madison Smartt Bell

Reviewed by Scott Blackwood, Fri., Feb. 2, 2001

Master of the Crossroads

A Novelby Madison Smartt Bell

Pantheon, 732 pp., $30

Master of the Crossroads, Madison Smartt Bell's second installment of his Haitian trilogy begun with All Souls' Rising in 1996, is the tale of the rise to power of Haitian revolutionary leader Toussaint Louventure. But Bell envisions the novel, and the trilogy as a whole, as much more than a sweeping historical saga. In a 1995 interview, Bell said that he intended the Haitian books as an inquiry into what it meant to be a human being. So from the outset, his ambitions were larger than, say, a historical novelist's like James Michener. And with Master of the Crossroads, he continues his literary inquiry based on exhaustive research of Haitian history (it contains a glossary of Creole terms, Toussaint's original letters, maps, and even an index of 64 different skin color classifications). But even though Bell is particularly adept at rendering, often at the same time, extreme cruelty, eccentricity, desire, malevolence, and indifference in his characters, these human complexities often seem at odds with the characters' more predictable actions, as if the story had already been written for them, rather than their actions folding out of who they are. In trying to have it both ways -- a historical novel and a literary inquiry -- Bell has misplaced something. In his desire to give us everything, in trying to evoke the physical, metaphysical, political, and moral dislocation of Haiti, some of the direct experience of it is, strangely, lost in the details.

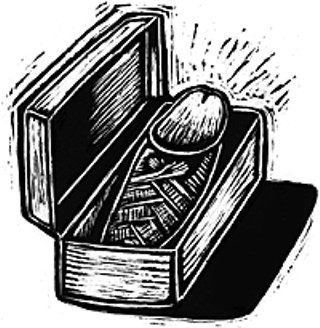

Toussaint Louventure is a shadowy, prophet-like figure throughout the novel, a human crossroads, where the physical and metaphysical meet. And as Bell no doubt intends, Toussaint remains more enigma than man. But enigmas lack warmth. So, as in All Souls' Rising, Bell gives the role of prime witness to the carnage of the slave rebellion to Antoine Hébert, a French doctor, who serves as the moral consciousness of the novel. Hébert, a sensitive, compassionate man, is set adrift in the winding currents of the rebellion (he becomes a ghost letter writer of sorts for Toussaint), and loses his mistress, Nanon, to a sadistic slaveowner's son in the process. He spends a good portion of the novel trying to retrieve her (emotionally and physically), just as he spent a good deal of All Souls' Rising looking for his sister. While on his quest, he encounters Madame Fortier, the sadistic son's mother, and she (besides reciting exposition, a clunky genre device that Bell resorts to too often), tells him to give up his pursuit and explains the meaning of the snuffbox Hébert carries as a talisman, and which Fortier's son left in place of Hébert's mistress. Their confrontation is hypnotic:

Madame Fortier took up the snuffbox from her lap and turned it so that it glittered in the light. "Of all I loathed about that man [Maltrot, the father of her son]," she said, "I most detested his manner of taking snuff. For he always used it as a seasoning of some abomination he had devised. ... But he has taken his last pinch." She opened her knees in a gesture that seemed almost lewd, letting the box fall back into the hollow of her skirts. She closed her thighs to hide the box, and rolled her weight toward the doctor. "Tell me, have you looked inside?" Her eyes shone on him strangely. "Do you know what it contains?"

The doctor swallowed. "The amputated sexual member, evidently mummified, of a human male."

"Why, you are absolutely correct!" Madame Fortier snapped her knees apart so sharply that the tightening skirt fabric catapulted the box into the air. She reached to catch it in one hand and, laughing gaily as a girl, offered it to the doctor. "Your prize, sir, is yours to keep -- so far as I'm concerned. My son ... presented it as a compliment to me. Tangible proof that he had severed the organ that planted the seed of him in my womb."

During this meeting, Madame Fortier also reveals to the doctor that the curious cases of infant lockjaw he has seen, from which infants eventually starve to death because they can't nurse, are caused by midwives surreptitiously sticking needles into the tops of the infants' skulls. In this way, Fortier informs him, "a child born into a world of hellish torments" can be released and go back to Africa. This image of self-genocide is joined in the novel by the vision of bayoneted white infants held aloft, their arms and legs flailing. These are signs of an apocalypse in motion, a primal evisceration of the human being as a concept. In other words, such political revolutions, Bell seems to say, tear apart and remake our idea of the human -- and these metaphors are first practiced, often horribly, on the body.

In these moments, when historical information is set aside and we're allowed to focus on the common horror, Bell's writing evokes a kind of macabre stillness. Elsewhere, particularly later in the book, Bell seems to strain for effect under the weight of the historical narrative. In certain chapters, particularly the first-person narratives with Riau, a sometimes deserter, sometimes captain in Toussaint's army, the heaviness of exposition seems particularly evident. And a number of the scenes, particularly with Doctor Hébert and Choufleur (Madame Fortier's cruel son), seem beyond plausibility and mired in cliché (though Bell seems to want us to link them to the heady mix of Voodoo and Christianity that wafts through the chapters).

In that 1995 interview at the outset of his Haitian trilogy, Bell said that the temptation in historical fiction is to generalize too much. But in Master of the Crossroads, he gives us such a detailed history that he sometimes neglects the most general thing of all -- what makes us human.

SMU Press will publish Scott Blackwood's debut collection of short stories, In the Shadow of Our House, in May