Taking Pictures

The Year's Best Photography Books

By Dick Holland, Fri., Dec. 15, 2000

Steichen's Legacy: Photographs, 1895-1973

edited and with text by Joanna SteichenKnopf, 400 pp., $100

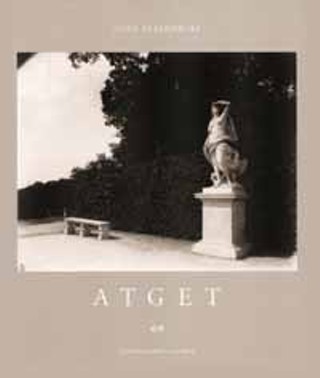

Atget

by John Szarkowski

The Museum of Modern Art/Callaway Editions, 224 pp., $60

Walker Evans: The Lost Work

by Clark Worswick and Belinda RathboneArena Editions, 264 pp., $65

How You Look at It: Photographs of the 20th Century

edited by Thomas Weski and Heinz LiesbrockDistributed Art Publishers, 544 pp., $55

Let's say you're feeling a little ambivalent about the holidays and have exercised some of your very best passive aggression toward the season by putting off the necessary task of shopping. Desperate, you stagger into a big bookstore, only to be assaulted by looming walls of coffeetable books, each one of them heavier and slicker than the next, all of them aimed at removing sizable assets from your bank account. Perhaps the worst offenders in this array of coated-paper dinosaurs are the so-called art books, 90% of which appear to be rehashed anthologies covering the same 30 years of French painting. It's enough to turn you against Renoir nudes and Monet water lilies forever.

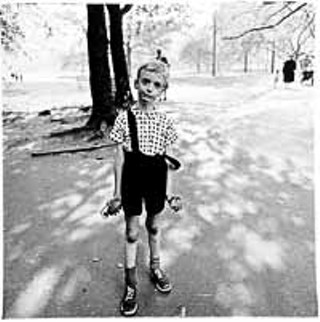

Here's a modest suggestion that will help save your shopping trip: Facing this ocean of mediocrity, cast your eyes a bit to the left or right, where you may see a separate section titled "Photography." Go there; it will restore your sanity. And particularly this year, because, for whatever reasons, we have been blessed with photography books of great beauty and intelligence. Several of the leading figures in the canon of 20th-century photography are represented in this season's unusually rich outpouring. This sterling lineup is led by Eugéne Atget, Walker Evans, and Edward Steichen, but there are notable guest appearances by Robert Adams, Diane Arbus, Brassaï, Larry Clark, William Eggleston, Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, August Sander, Cindy Sherman, Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand, and Garry Winogrand.

The mainstream blockbuster book of the season, without a doubt, is Steichen's Legacy: Photographs, 1895-1973, edited and written by Joanna Steichen, who married Steichen when he was 80 and she was 26. This lavish production reproduces more than 300 of Steichen's images, many of them newly printed from his negatives by the master printer George Tice. This is the first career examination in 30 years of Steichen's enormously long and influential life as an artist and curator. Seeing all of his work together, freshly and beautifully printed and intelligently arranged, provides a quick education in the history of photography.

Progress in photography has been largely determined by technology and invention, and Steichen's seven-decade-long career extends back to the end of the era of glass-plate negatives and excruciatingly long exposures. He appears to have subscribed to his mother's belief that he was possessed with genius, and by the mid-1880s he was part of a burgeoning art scene in his native Milwaukee. In 1900 he moved to Paris, which until the coming of the Great War in 1914 was the very center of Western art. Still carrying the aesthetic of American painters in Europe such as James McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent, Steichen immediately formed friendships with major figures in the Parisian art world, particularly the sculptors Rodin and Brancusi. Working out of the tradition of soft-focus pictorial photography, Steichen's stunning photographs of Rodin's work (particularly the monumental sculpture of Balzac, shot in moonlight in Rodin's garden) crossed the line from portrait photography to photography as interpretation or collaboration. During the same decade in France, Steichen became a pioneer in color printing, being one of the first to use the Lumiére brothers' autochrome process. His palette reflects a fin-de-siècle romanticism, one that was soon knocked out of him (and everyone else) by World War I.

In almost every branch of photography, Steichen is presented as the precursor to later excellence in different genres. In this book that is especially true in his fashion and celebrity portrait work. Steichen's unforgettable photographs of J.P. Morgan, Greta Garbo, and Gary Cooper, just to list three iconic examples, almost feel as if they have become part of the tactile content of American history. The work of later photographers as talented and diverse as Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, and Annie Liebowitz can be viewed as growing from Steichen's work in the two decades following the First World War. By the 1940s and 50s, Steichen's example as a war photographer had clearly influenced the great body of photojournalism that was then burgeoning in American magazines such as Life, and in his great landscape work, he both anticipated the color work of Eliot Porter and returned to his romantic origins with his late close-ups of flowers.

In many ways, Joanna Steichen's book is a work of rescue. By the 1950s, primarily because of his popular worldwide exhibition, "The Family of Man," Steichen was regarded by serious photography people as something of a popularizer. Joanna Steichen's text demonstrates that not only was Steichen a seminal artist himself, but that he was invaluable as a promoter of Cézanne, Rodin, Brancusi, and Matisse, among others. When she met him he was occupied with institutional work as curator of photography for the Museum of Modern Art, where he helped create the idea of photography as an art form to be collected and studied.

John Szarkowski followed in Edward Steichen's footsteps as photography curator at the Museum of Modern Art. In that capacity he broadened the museum's taste in photography by embracing the new generation of Diane Arbus, Elliott Erwitt, Robert Frank, and Garry Winogrand. At the same time he produced books that steered the art in a brand new direction by providing brilliantly written observations on the art and social utility of taking pictures. The best of these was Looking at Photographs, published in 1983, a survey of 100 images taken from MoMA.

Atget is still a little difficult for the beginning photography buff because of his hidden personality and cryptic subject matter, made up of quirky late 19th-century glimpses at the French countryside and the darkest corners of a largely unpopulated Paris. In his introduction, Szarkowski places Atget in the changing photographic technology of his times. There were two major departures in the late 1800s that made possible the new age of documentation: the invention of the commercially available dry plate and the ability of periodicals and newspapers to print pictures on regular paper using ink.

After the invention of the dry plate the photographer left his laboratory at home, and until the invention of the automobile he could shoot in a day more plates than he could carry. After the automobile there was no limit.

Photography had been from its beginnings quite permissive about what subjects were worth recording. ... But with the dry plate the bar was dropped virtually to the ground. Now almost everything was photographed: not only masterpieces, but every old painting, every ancient pot, every banquet, every school class, almost every picnic.

Atget's place is Paris and its outlying areas and his period is the same as Proust's. As a first-generation documentary recorder, he seems almost entirely disinterested in the human population of the place, turning his formidable eye to recording the streets, buildings, shop windows, and particularly the gardens that he visited, usually very early in the morning. He appears to have had a special attraction to the abandoned building, the ruin, and the overgrown garden.

Atget's point of view is often odd and off-center, creating images that give a fresh look at subjects that, interpreted by a lesser photographer, would resemble illustrations in a travelogue. Most of all, he invented shadow and reflection both in the natural world of trees and ponds, but also in the streets reflected in shop windows full of mannequins. The resulting images are still, yet full of movement, and above all coolly reticent. About this quality, Szarkowski concludes:

The pictures are never quite what we would have expected. They are never quite perfectly resolved in their sentiment -- contradictions are not edited out. They are disinterested -- free of special pleading. They are brave -- in the sense that (we feel sure) nothing is made to look better or worse than it looked to the photographer. They are dead-on accurate -- in the sense that they allow us to know that these scenes will never again look as they look in the pictures. They are as clear as good water, as plain and as nourishing as good bread.

In Atget, Szarkowski nominates Walker Evans as Atget's natural inheritor: "It seems now that Evans worked his way through Atget's whole iconographical catalogue, save only the parks. Evans did the bedrooms and kitchens, the boutiques, the signs, the wheeled vehicles, the street trades, and the ruins of high ambition." In Walker Evans: The Lost Work, photography historians Clark Worswick and Belinda Rathbone work to create an appreciation of Evans' full career, which stretched from 1928 to 1974. Evans has been almost too warmly embraced as America's greatest documentarian. The very idea that Evans, whose work was the subject of a major retrospective last year at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, could have "lost" work comes as a surprise, although a most welcome one, as it turns out.

Worswick maintains that it is only the seven notable years in the 1930s when Evans documented the South (resulting in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, written by James Agee) that has interested collectors and museums. He begins his essay with a description of meeting Walker Evans in 1966 at a lecture at Harvard (attended by only 15 people) just before Evans, then at the age of 63, was about to have his first one-man show in New York City.

Next Worswick relates the fascinating story of how Evans, dying of alcoholism in the mid-Seventies, was perhaps exploited into selling his entire private collection of prints and negatives to a photography dealer for $100,000. (Lest we die of shock at this absurdly low sum, he reminds us that the Museum of Modern Art paid Berenice Abbott only $50,000 for all of Atget's prints.) The dealer/culprit in the Evans deal was named Rinhart, and there is a colorful description of him hauling off Evans' life work in the back of his Rolls Royce. After another squalid transaction, this tremendous treasure of 20th-century art ended up in the hands of another dealer, the notorious Harry Lunn, a former CIA man. All this would be nothing but dated gossip if it were not for the fact that Worswick came to know the full range of Evans' work through these comprehensive collections.

Although a bit light on Evans' famous photographs from the Thirties, Lost Work demonstrates that, like Atget, Evans enjoyed anonymity and to some extent even saw photography as a form of social subversion. Belinda Rathbone is an Evans biographer, and in her essay she points out that Evans liked nothing better than walking into his friends' homes, snapping pictures before they had a chance to straighten up. This interest in life as it is lived was perhaps most evident in what was called his "Subway Series," in which Evans sneaked a concealed camera onto a New York subway car and photographed his fellow passengers totally unaware.

Last and not really least in this lineup of holiday recommendations is a German compilation (with text in English) titled How You Look at It: Photographs of the 20th Century. An exhibit catalog prepared by the Sprengel Museum in Hannover, How You Look at It is a world away from the hovering sense of hagiography present in the books on Steichen, Atget, and Walker Evans. This book is much more concerned with the social impact of photography, in presenting a hit-and-run aesthetic of shoot the picture and speed away, and in juxtaposing unlikely artists together. This approach is inspired by collage, and matches the photographers Robert Adams, Diane Arbus, Atget, Karl Blossfeldt, Brassaï, Larry Clark, Nicholas Nixon, August Sander, Charles Scheeler, Cindy Sherman, Stephen Shore, and Garry Winogrand (and others) with a large array of painters that includes Francis Bacon, Edgar Degas, David Hockney, Edward Hopper, Jasper Johns, Pablo Picasso, Mark Rothko, and Andy Warhol.

Topics discussed in the challenging text include fatalism in landscape photography, the endangered future of "quiet" photography, photographic language in the digital age, and photography's slippery relationship with "reality." If this sounds a bit like graduate school, perhaps it is, but at least you won't be graded, and if you get bogged down in the words, you can always turn the page to find more and more great pictures.