The Undoing of Nonet

This unsettling dance by Kathy Dunn Hamrick seemed a companion piece to her shattering work, The Big Small

Reviewed by Jonelle Seitz, Fri., Dec. 13, 2013

The Undoing of Nonet

Salvage Vanguard Theater, 2803 Manor Rd.Dec. 6

"It's not the lightest work I've ever made," said Kathy Dunn Hamrick during her preshow introduction of The Undoing of Nonet. But it wasn't the most devastating, either. The 50-minute piece, danced to two vastly different pieces of music performed onstage by the percussion trio line upon line, was less shattering than Hamrick's The Big Small, which premiered in June. I was glad I'd seen both. While The Big Small considered a catastrophe, Nonet was quietly unsettling, depicting the undercurrent of malaise in the keepin' on and inevitable unraveling that might have followed that event.

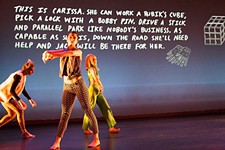

Nonet refers to the nine dancers in the group, which was experiencing an actual undoing, as eight-year veteran Roxanne Gage was set to retire after the performances. At first, the dancers, costumed in variations of beige day-wear (by Laura Noose and Mandie Pitre), moved as one organism, forming soft shapes in silent waves until a mallet made a ground-splitting strike on a drum and one dancer tore herself away from the chain. This point seemed overamplified, but I realized later that I needed such calling of attention to important moments: Because I was watching the musicians, I didn't notice when or how the first dancer left the stage. But then there were eight.

Hamrick developed the dance without music, selecting Iannis Xenakis' "Okho" and Ben Isaacs' "several inflections" from line upon line's repertoire six weeks into the process. "Okho" is loud, dynamic, aggressive; the musicians moved their mallets down to the drums as butchers with meat cleavers, and the dancers were at times propelled by their rhythms. But "several inflections" is a subtle, constant, tiny composition for three partial glockenspiels no bigger than babies' xylophones, which were played with red mallets thin as chopsticks. The intense concentration required of the three men to make these tiny, sustained sounds seemed to suggest a madness, or the oblique focus that makes art, in general, possible.

During "several inflections," the number of dancers onstage dwindled to five, and they required more of one another. Each took turns lifting others to help them raise their limbs toward the ceiling. The lighting, designed by Stephen Pruitt, came from 65 or so halogen bulbs suspended from a wooden grid above the stage, and whenever a dancer's toe or finger brushed one of the bulbs, the entire apparatus swayed. Near the end of the piece, groups of the lights flickered, as if their power source was faltering. Soon after, the instruments' final tones faded into nothing, and dancer Shari Brown was alone, curled, just off-center. She stayed there long enough that, as though seasons had passed, her crouching human form surrendered its defense and became a beautiful, earthly shape.