'Roy Lichtenstein Prints 1956-97'

AMOA's exhibit reveals how our desires are formed by primary colors, Benday dots, and thick black lines

Reviewed by Nikki Moore, Fri., Jan. 11, 2008

'Roy Lichtenstein Prints 1956-97'

Austin Museum of Art – Downtown, through Feb. 3

Do you remember your first movie – your first encounter with characters both larger than life and yet somehow just like you? If you left the film inspired, admiring, more knowledgeable, or, in the case of horror, scared, you are probably in the majority. But how often have you left a film feeling mechanically coerced? More than likely coercion is not why you paid to sit before the big screen, but according to many contemporary philosophers and film theorists, the movie industry is a culture industry, a desiring machine that slowly but steadily teaches you how to desire, what to desire, and when to desire it. And we're not talking about adult films or films on power and relationships; we're talking about every movie from Psycho to Bambi. Apparently, it works by repeatedly packaging emotions, scenarios, personas, and combinations in ways that are both familiar and seemingly "natural." Then these tacit clichés map out every facet of our lives, from what to eat to how to love.

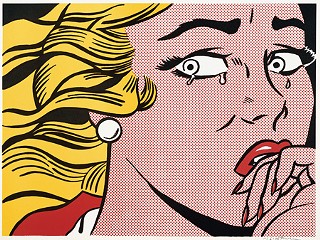

But historically, movies were not the only media to bring the culture industry to the general public. "Roy Lichtenstein Prints 1956-97" suggests the role that comic books and other pop-culture graphic arts played and still play in setting standards for our hopes and desires. Showing off more than 70 prints and a career's worth of work, this Washington State University traveling exhibition, currently at the Austin Museum of Art, demonstrates how Lichtenstein employed and advanced printing techniques to explore how cliché in pop culture, with aid from various mechanistic technological advancements, helped form these desires. In works such as his famous Crying Girl (1963) and others, Lichtenstein constructs "images of beauty" from the calculated use of techniques employed by comic-book illustrators: three primary colors, Benday dots, and carefully placed black lines. When asked about his own susceptibility to the beauties he created, Lichtenstein replied that to him they are "really made up of black lines and red dots. I see it that abstractly, that it's very hard to fall for one of these creatures, to me, because they're not really reality to me." Yet the enduring contemporary power of Lichtenstein's work matches back up with media studies and philosophy precisely at the point where we recognize that our everyday assumptions and constructions are often little more than a series of lines and dots that we learn to connect over time, over books, over film, over art, and even over comics.