‘Mary Lee Bendolph, Gee's Bend Quilts and Beyond’

The Austin Museum of Art's exhibition 'Mary Lee Bendolph, Gee's Bend Quilts, and Beyond' prompts one viewer to piece together a story about postmodernism from patches of art and ethnology

Reviewed by Nikki Moore, Fri., Sept. 15, 2006

"Mary Lee Bendolph, Gee's Bend Quilts, and Beyond"

Austin Museum of Art, through Nov. 5

In 2002, a group of women and quilts from what was once a small sharecropping community in Alabama went national, proving that there is literally no time like the postmodern present for quilting. As Austin Museum of Art Executive Director Dana Friis-Hansen writes in notes for "Mary Lee Bendolph, Gee's Bend Quilts, and Beyond," "Postmodernism in the visual arts represents an attempt to move beyond the hegemony of the white, male, Eurocentric ideas and forms that were the basis of modernism and that served as the standard by which all other ideas and forms were measured." In this new climate, groups and works that were previously cloistered off as "folk" are now making their way onto some of the art world's most exclusive wall space.

The results are as varied as the quilts which have come to symbolize this opening, leaving room for both doubt and celebration. For certainly, on one very important hand, it is high time for some of the world's most expressive and significant art forms and artists to make their way into a limelight once reserved solely for the painting and sculpture of the status quo. The Gee's Bend quilts and their quilters tell rich stories of tradition, of innovation, of social realities, and of family ties. Without a doubt, these are stories worth telling, beauty and intricacy worth revealing. But on the other hand, there is a part of this opening up of the art field to those who have long been considered outsiders that still carries the paternalism of Levi Strauss and the early ethnologists who cried, "Look! Look at this beautiful culture I have found! Look how like or unlike me it is."

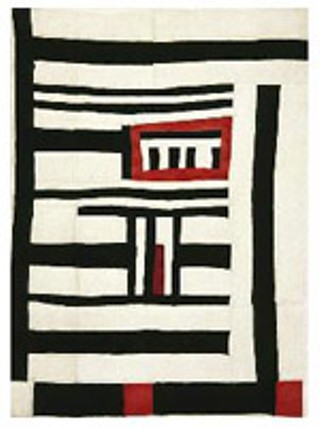

Merely glancing at the Gee's Bend quilts reveals a parallel to modernist aesthetics, in their bold color fields and simple abstracted forms. While this is decidedly not a blight on the work itself, it is interesting to wonder if, had these quilts been otherwise, their impact would have been so profound and pervasive. When Mary Lee Bendolph first began the work of quilting, passed on to her by her mother as it was passed on to all young girls of Gee's Bend, she lived in a home without temperature control or much money for extemporaneous spending and was part of a culture that looked at quilts as warmth, albeit beautiful warmth, on walls, beds, and laps alike.

The consequences of "being noticed" and the inherent changes that take place within a "watched culture" have not been lost on Gee's Bend, with primarily positive consequences: A group formerly unconsidered by the outside world has now found recognition and praise for its work, diligence, and artistic integrity. The art of quilting, which was fading in Gee's Bend before "The Quilts of Gee's Bend" exhibition in 2002, has been revived, and the quilters are finding artistic fellowship in mutually enriching art-tethered relationships.

But of course, as with all ethnology projects, postmodernism's obsession with openness has its dark corners and its points which change things, art, and people, irrevocably, for better or worse. It is most often these effects that ethnologists hope no one will ever "Look! Look! Look!" into. Yet I am not suggesting a return to some "real" or "authentic" Gee's Bend quilting culture that occurred prior to exposure. The women of Gee's Bend deserve the praise they are rightly receiving, their lives have been enriched, these are things we all dream of – I am only trying to piece my own quilt, my own thought fields, points of interest, and conflicts into a story about postmodernism. Of course, it is this very opening up that is allowing me, a woman, to write this review in the first place. It makes one pause. It makes one pause.