Chopper

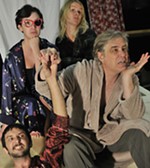

Leah Ryan's 'Chopper' has the quirky characters and bizarre humor of many Hyde Park Theatre productions, but sympathizing with its disconnected characters is difficult

Reviewed by Barry Pineo, Fri., Nov. 4, 2005

Chopper

Hyde Park Theatre, through Nov. 19

Running Time: 1 hr, 15 min

The room is wasted, one of those city slumlord specials, dirty brickwork enclosing studs exposed on the inside through misuse or vandalism, flimsy front door that barely closes, catering to the lowest common cultural denominator. There's not much furniture outside of a tiny TV on a milk crate. Old newspapers, popcorn, and empty cans of Pabst, Miller, and Schlitz litter the floor.

It isn't a pretty picture, but it isn't meant to be. The two inhabitants of the room are Kathleen and Emily. They've known each other since high school, Kathleen, all tough surface and flip-the-bird attitude, dropping out at 16 to be "free," and Emily, not too smart but more than a bit manipulative, being institutionalized by her rich parents before she even has a chance to graduate. Kathleen has a boyfriend she's known since the sixth grade named Fred (or Mick, take your pick), who lives in his car and was recently dumped by Kathleen, probably the single most intelligent move she's ever made.

This is the world of Leah Ryan's Chopper. Hyde Park Theatre Artistic Director Ken Webster is at the helm here, and the play has the qualities of so many HPT productions: quirky characters living on the edge but managing to maintain bizarre senses of humor. Webster has the actors keep the action quick and loud and stages the show simply, often letting scenes play through without ever utilizing any physical movement to speak of. The first scene is a good example: Kathleen and Emily sit on the floor in front of their tube, watching the news with the sound turned down, fantasizing about the weatherman and Chopper Dave, the traffic guy, with whom Kathleen is enamored, never moving except to drink or smoke or eat popcorn. They almost never look at each other.

Sympathizing with these disconnected characters is difficult, and that's strange especially for me, because I presently find myself in a similar situation. At one point, Kathleen began to cry, and seeing that soft center in that tough façade was moving, but for the most part I was unmoved. There's humor in Ryan's script, most ably embodied here by Noah Neal in multiple roles, but the humor tends to get buried under a sameness of tempo and volume. While there are pauses and silences, they only serve as prelude to more of the same; it's loud and quick, but it doesn't go anywhere. In addition, Ryan has the play jump back and forth in time, but with little delineation between what's past and what's present, so little that, at the conclusion, I wasn't sure what time I was observing. I felt confused and kind of empty, struggling more than a bit to understand what I was seeing. But perhaps that was the point. So many of us, it seems, live our lives in shells, alone and disconnected, pounding our heads against the pointlessness of it all.