Weird Science Takes the Stage

The strange, true tale of how a high school science textbook was turned into a play

By C. Denby Swanson, Fri., Feb. 6, 2004

Think of the word "biology."

What do you see? Frogs. Formaldehyde. Dissection tools. The parts of a cell. Kingdom, something, something, family, genus, species.

My biology teacher in ninth grade was a tiny, stringy woman in her mid-60s. I don't remember her name, but I remember her hard, terrifying eyes and the scalp visible through her thinning, feebly curly hair. She sent me to the principal's office once for wearing shorts to school. The vice-principal cut the threads that held the cuffs up above my knees, which was the Mason-Dixon line for pants length in League City, Texas, in 1984, and pointed me back to my classroom. I also remember that my biology teacher insisted that women couldn't feel themselves ovulate. In fact, that's all I remember about our entire sex-education section. The very idea made her livid. "You may think that you can," she admonished, her voice rising, "but you can not feel yourself ovulate."

One day, for a very difficult exam, we were to write an essay explaining the process of evolution. My response was sort of a Hail Mary at the buzzer; completely unable to organize a scientific response, I wrote a short story about a family of squirrels who were separated from each other by some natural disaster. An earthquake, something like that – a divide. Different environmental factors led to the survival of different characteristics, led to different species. The squirrel family reunion was a disaster, but in terms of evolution, we got the gist.

My biology teacher read my story out loud to the class. I don't remember if the shorts issue came before this or after it. In either case, it was weird to be, even briefly, her favorite student.

In the spring of 2003, I had a conversation with Clay Nichols, the head of Theatre Focus at St. Stephen's Episcopal High School, about an adaptation project that I was going to lead with Troupe St. Stephen's, the school's performance ensemble. For the last four years, the troupe has created, produced, and toured a new play. Each has had a different core idea: a story about Johnny Appleseed, for instance, or the sonnets of William Shakespeare (which they worked on in 2002 with the Rude Mechanicals).

"What do we want to adapt?" Clay asked. I said, "Gee, I dunno." He said, "Well they're studying Pride and Prejudice in English." I said, "Do we really need another stage adaptation of Pride and Prejudice?" He said, "No, you know what we need is a starting place that has nothing to do with theatre whatsoever, something that's not related as literature, not even related to the humanities. What we need is a science. What we need is ...

"Biology."

The Improbability Factor

Here's part of the subsequent conversation I had with myself:

"You're adapting what?

"A ninth-grade biology textbook.

"A what?

"You heard me.

"Did you like biology when you were young?

"I'm still young.

"You know what I mean.

"No.

"How long does it usually take you to write a play?

"Eighteen months.

"How long do you have for the biology project?

"About six weeks."

The strength of the biology play project was its very unlikelihood. It was an unlikely combination of science and theatre, and it was unlikely that it would actually get done on time. Fortunately, the process was like any good fairy tale: Along the journey, you meet the people whose skills you will need to complete the journey. In June, at the International Thespian Festival in Lincoln, Neb., where I was teaching and dramaturging, I had a conversation with Doug Rand, the president of upstart publishing company Playscripts Inc. (www.playscripts.com). He is a writer himself and, as it happens, the publisher of two of my one-act plays for young people. I mentioned to him this impossible-sounding prospect for a play, and he had several great ideas for a story. Then he had a couple more. And I must have looked at him strangely, because he said, "Oh, you probably don't know that I have a master's degree in evolutionary biology from Harvard." I was like, you're coming with me down the yellow brick road, pal.

Between June and September, Doug and I spent hours and hours each week talking about potential story ideas, places to start working, and how to spend the first day of rehearsal. One Sunday evening, I covered the front of the New York Times Book Review with scribbled notes. For example:

Malthus: death & hunger as a necessary check on population growth

Steven Jay Gould – no preordained path toward humans (or toward insects)

Nothing is planned

What is the theatre of biology? How did this happen, not how does it work

Anything is possible given enough time – bacteria can turn into cheetahs (add selection pressure)

And, my particular favorite:

Darwin & Wallace were beetle collectors – Britain – relatively species-poor – why are there so many Beatles?

Who Wants to Experiment?

We held auditions the first week of September, at the same time as auditions for the school's mainstage show, Noises Off. You audition for a production and for an ensemble development process in very different ways. A production already has a script, so auditions are about matching the right actors to existing parts. The biology play didn't have parts yet. It didn't have a basic story. It didn't even have a title.

Our auditions were about working together, about commitment to big, physical choices. I gave each group of five a long, yellow clothesline and said, "Here. Create a scene in which everybody participates. Rehearse it. Get it ready for me to see. You have five minutes."

In two hours, we'd found an amazing cast. Kathleen had a strong opinion about everything. "Oh, that's the ninth edition?" she asked. "I hate that edition. It has such misinformation about anorexia nervosa." Excellent, I thought. She's going to keep us in line. Sunny watched everything intently. She had to; she had arrived in Austin from Korea just two weeks before, and her English was limited. Excellent, I thought. Everyone will adapt. Ryan threw himself into the audition – he was a smartass, he was physical, he let his group wrap him in the clothesline and unwrap him as a new butterfly. Excellent. Abby was a rush of energy, smart, creative, generous. She offset Ryan's butterfly as a mewling, newborn infant. It was magnificently weird. We also found Lizzi, Kate, Marjorie, Lauren, Aaron, and Selina. Each actor was distinctive, promising, curious, agile, attentive. "What is this play going to be about?" someone asked. I held up the 800-page textbook and replied, "Let's find out."

"But what if it's just awful? I mean, biology?" remembers Abby. "I went into the first rehearsal wearing my confidence dress: red with bright white-and-green flowers and a swooping skirt."

The Egg

We started off our rehearsal process with questions. What's your favorite thing about biology? What is evolution? Why do men have nipples? We wrote responses down on big pieces of paper and then taped them to the walls. One of Ryan's answers was, "Men have nipples?! Oh, wait, I guess we do."

We spent two days dissecting flowers and fruits, including a Vietnamese specimen called a durian. Ours, picked up at a market on North Lamar, weighed more than 10 pounds and was covered in sharp spikes. "It grows on trees," Doug told the group. "And when it ripens enough to fall to the ground, it can kill people." The meat inside is the consistency of congealed lard, it smells like rotting garbage, and it tastes like a combination of onion and vanilla. It was oddly delicious. But I think there was overall a more positive culinary consensus about the pomegranate, the inside of which Abby described as being "so female they were practically giggling and buying tampons."

Later that week, we went to the Austin Zoo, which has eight species of primates, including monkeys who used to live at a research lab, and lions, tigers, panthers, and other big cats rescued from a "religious circus." We came home from that trip with all kinds of gestures and shapes and questions to ponder: Why do goats have sideways pupils? How do turtles grow their shells? Why do those monkeys have white ear tufts, and others don't?

We were figuring out that, as a subject for a play, biology makes a very cool theatrical sense. Like Shakespeare, it's about life and death struggles: All the world's a stage. But it was important to me from the beginning that this project not be about biology as an academic subject. Neither audience nor actor should wonder when the pop quiz is coming. I flipped through the pages of the biology textbook. Our play couldn't be about facts, it had to be about relationships.

Here are the ones we used:

I split the cast into three groups. I told them they had to write a monologue using Wallace, Darwin, or Alvarez in some way of their own choosing, although it did not have to be from the scientist's perspective or even historically or factually accurate. This is where we had to start moving away from what we knew and toward the drama, the experience of not knowing, the experience of venturing out on our own, the imagination.

Here's what they came up with: a monologue of Alfred Russell Wallace in a 1970s disco, trying to use pickup lines about evolution on Farrah Fawcett; an old man, Abe, telling a muddled and fantastical story about Walter Alvarez to the ghost of his dead grandson; and M-Dogg, the Malaria Bitch, a hip-hop protozoan in Wallace's bloodstream, talking about the discovery of natural selection and Wallace's interaction with Charles Darwin.

It was magical.

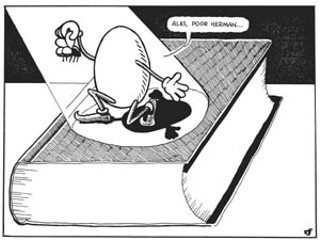

Wallace eventually fell by the wayside, but we kept Abe and M-Dogg. We turned Abe's grandson into a nephew and called him Dead Peter. We also added Betsy, Abe's pet dinosaur, who is looking for her long-lost egg; Abe's wife, Bathsheba; Herman, a fly with 24 hours to live; the Fly Girls, whom Herman tries to date; the three Fates; a rodeo version of Walter Alvarez; and three Flowers who have been kidnapped by a young Girl.

Then, Ryan Sullivan, the director, mentioned in passing this crazy idea he'd had: Wouldn't it be great if we created a primate band? So we had the cast explore monkey gestures adapted and abstracted from what we'd seen at the zoo. Lauren came back from having her wisdom teeth pulled with two of the three songs we'd eventually use for the All Chimp Runaway Lab Monkey Band. I'm a huge fan of their anthem, "Monkey Zion." The chorus goes like this:

LAB MONKEY #1

Jane Goodall! Jane Goodall!

Ooooooo

Aaaaaaaa

LAB MONKEYS

Lead us to the Promised Land

The Monkey Promised Land

Monkey Zion! Monkey Zion!

When you thought of the word biology, did you think of this? No. I didn't either.

"It's Alive! It's A-live!!"

In early September, Doug and I were fortunate to get to the final day of public input on the inclusion of creationism in public high school biology textbooks. More than 160 people signed up for three-minute blocks of testimony. Talk about a zoo. One of the people opposed to evolution testified that a computer program he'd helped write had proven that the odds of life happening on its own, without some intelligent designer, were one in 10 to the 40,000th power.

That statistic continues to make me think about the near impossibility of creation. Yet it happens. How? The divine? Sure. Two different single-cell organisms that randomly bump into each other? Sure. I mean, either way, it's about being open to change; it's about walls coming down; it's about the unexpected and the unknowable. There was no one moment when our biology play came together; rather, there were many moments, most of which I didn't recognize as moments until weeks later, and by then we had made something. Things grew to fit the play. Other things, although they were imaginative and lovely and inherently good things, didn't. Creation. Evolution. Same thing.

By the beginning of October, we'd found in our rehearsal and creation process a variety of characters who had life, characters who defied our expectations, who were abrasive or impossible or, simply, in some small way, wondrous. But we were missing something. I finally cracked opened the biology textbook.

The ninth edition, like its predecessors, is supposed to be an objective, clinical explanation of the natural world. But there on the first page was something different. The authors describe how a spider eats an insect – by liquefying its prisoner's insides with a toxic poison and "sucking up the resulting broth." I stopped reading. Sucking up the resulting broth? Hold on just a second. That's not clinical. Someone is getting a huge kick out of that image.

The Biologist said his first words to me. "Think of the word broth."

What are we? We are what we eat. We are the sum of our parts. We are sugar and spice and snails and mitochondria – separate organisms with separate DNA from ours that we are somehow born with. How freaky is that? That's what our play is about, in some ways. How long has it taken us to get here? "As long as it took everything so far to happen," says the Biologist. There was the title.

Everything So Far had its world premiere at St. Stephen's on Dec. 11, 2003. We rehearsed until 7:15pm. The house opened at 7:20, and the curtain went up at 7:35. Our set consisted of two chairs and a yellow table. The Lab Monkeys made music from an odd collection of medical equipment that I found in a store in St. Paul, Minn., called Ax Man – gloves, plastic syringes, beakers, things that clicked and shook. Lizzi had a severe flu that week. Between the end of rehearsal and the opening lines of the show, she went backstage and threw up (and then, what I love best about that day, she went on with the show and performed flawlessly). On Dec. 12, we performed the show in a different space on campus, smaller, with about five lighting instruments and a CD player for the sound cues. The room was packed. Selina said her opening line as Dead Peter: "I'm dead. Don't worry. It's OK." It was great.

On Dec. 14, Troupe St. Stephen's performed the show at Odyssey School, a school for middle school students with ADD and ADHD, where Troupe director Ryan Sullivan also teaches. In a dance studio with no curtains, much less wing space, no prop table, and one wall of floor-to-ceiling mirrors, the cast held the attention of those kids for more than 70 minutes straight. This month, Troupe tours the play to Episcopal schools in Central Texas. In April, they perform at an arts festival in Dallas. Clay Nichols wrote me recently to say that this quirky play just keeps on growing on him. It is exactly what we had talked about in our first conversation, and it is also, fortunately, its own animal.

Everything So Far takes us on an unexpected journey. We get really, really far away from where we thought we'd go. But somehow it all comes together. Early in the play, Dead Peter introduces the other characters by announcing a "book dance." Everybody brings on their favorite book: the Bible, the collected works of Shakespeare, a book of Greek myths, Goodnight Moon. They leave their books in a messy pile that will transform into both props and set. The Biologist brings out his textbook, which eventually becomes a geologic layer of earth for Alvarez to dig in, as well as one wall of a house that the Fates build. We go backward in time. Herman the fly dies. In fact, there's a lot of death in the play – but it's quiet. It's funny. We understand the cycle. We understand a lot more about biology that I thought we would. And we have written a pretty great story. ![]()

Troupe St. Stephen's will tour Everything So Far to Good Shepherd Episcopal School and St. John's Episcopal School on Thursday, Feb. 12, and the Parish Episcopal School on Friday, Feb. 13. Some public seating is available. For reservations, call Clay Nichols, 327-1213 x679.

The play will also be performed at the Independent Schools Association of the Southwest Fine Arts Festival at Hockaday School in Dallas on April 15-17.

C. Denby Swanson is a graduate of UT's Michener Center for Writers and a former Jerome and McKnight fellow. She currently lives in the New York City area.