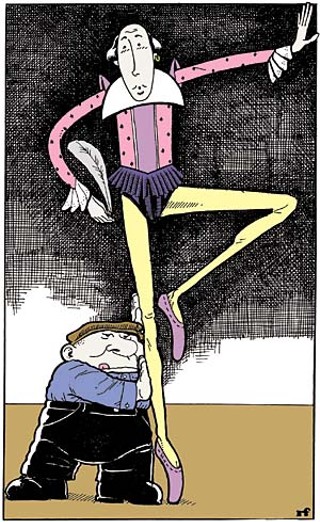

Shakespeare-ouette

Stephen Mills has a deft touch at getting the Bard to the barre

By Robert Faires, Fri., Oct. 10, 2003

Kate comes out swinging. She's not about to suffer the indignity of this smarmy lout Petruchio hitting on her like some cheap babe. She swings a haymaker at his grinning puss, jabs an elbow in his breadbasket, shoots a lethal kick at his jutting chin. To his credit, Petruchio parries most of these thrusts and gives as good as he gets, thwacking Kate on the fanny, grabbing her outstretched leg and pulling her up onto his shoulder, then pulling her forward so that she tumbles to the ground upside-down.

We've seen this pair mix it up before, if not on a stage, then on film as embodied by Liz Taylor and Richard Burton or Kathryn Grayson and Howard Keel. These are two of Shakespeare's most memorable lovers -- memorable precisely because their romance gets its start in combat, overt hostility expressed in bruising deed and slashing word. This time, however, the words are missing, as Kate and Petruchio's slugfest/courtship dance is being performed by classical dancers. Ballet Austin Artistic Director Stephen Mills has turned The Taming of the Shrew into an original ballet, and its premiere this weekend at Bass Concert Hall will mark his fourth adaptation of a Shakespeare play in the past five seasons. If his previous three efforts are any indication, this one will be as satisfying an experience of Shakespeare as almost any production of the play itself.

So, how has a choreographer become one of our city's premier interpreters of Shakespeare? And how does he go about bringing the Bard to the barre? For the answers, position your arms in front of you, lift one leg, and ...

Turn counterclockwise four years: Another Shakespearean heroine comes out swinging. This one, Hermia, wants to punch the clock of her dear childhood friend Helena for stealing her boyfriend. (Actually, he's just under the spell of some magical love juice that has caused him to fall head over heels for Helena.) Hermia's feelings of betrayal and desire for payback are expressed by the Bard in these immortal lines:

And are you grown so high in his esteem;

Because I am so dwarfish and so low?

How low am I, thou painted maypole? Speak:

How low am I? I am not yet so low

But that my nails can reach unto thine eyes.

And while they are not spoken here, we hear them in the furious gestures of the ballerina, clawing at the air, frantically seeking to hurl herself at her friend, only to be held back by the men on either side of her. This is Stephen Mills playing with the Bard for the first time, choreographing a new version of A Midsummer Night's Dream. After the success of Cinderella, his first-ever full-length ballet in 1998, Mills needed a follow-up project, and he turned to a story he had known since childhood but that hadn't been widely performed as a ballet, a work that would be fun to choreograph and would allow him to include lots of the physical humor he loves. Even though he has to condense all five acts into an hour's worth of dance, Mills still spins the full story -- from runaway teen lovers and feuding fairies to the rustic who winds up with an ass' head and the wedding of warriors -- and, even more impressively, communicates the spirit of the work in all its scope: the romance, the folly, the irreverence, the bawdiness, the wisdom.

Turn clockwise 19 months: Mills returns to Shakespeare, but with a work that is a far cry from the Dream, with its slapstick and fairy pranks. This time, Mills moves from the depths of low comedy to the lofty heights of tragedy: Hamlet. To the music of Philip Glass, dancers in Armani suits and high-fashion cocktail dresses play out the story of the Prince of Denmark. Despite the dramatic differences in style and story, Mills' facility in translating Shakespeare's text into dance holds true. In his review for the Chronicle, Rob Curran notes of the closet scene: "All the guilt, accusations, and twisted love between Hamlet and his mother in her chamber emerged through body language."

Present at one performance is Derek Gordon, vice president for education at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. He is so impressed with the company and Mills' work that he invites Ballet Austin to Washington, D.C., to perform as part of the center's Youth and Family Public Performance Series.

Turn clockwise another 15 months: In the first week of 2002, just two months after giving the company its third Shakespearean ballet, an eloquently passionate Romeo and Juliet, Mills leads Ballet Austin to the nation's capital to present an abbreviated version of his A Midsummer Night's Dream in the 513-seat Terrace Theater at the Kennedy Center. Despite the fact that the company is not well known outside Texas and that box office for events around the new year is traditionally sluggish, the Ballet Austin shows sell out. Moreover, the work generates enthusiastic responses from the crowds and a glowing review in the Washington Post. The acclaim prompts Derek Gordon to invite Ballet Austin to return to the Kennedy Center. Mills isn't sure that the company has a piece in its repertoire that is appropriate for the venue or that space, so he and Gordon brainstorm about other possibilities, new works that Ballet Austin might develop that the Kennedy Center would be interested in seeing.

Turn counterclockwise 410 years (give or take a few months): That upstart crow, Will Shakespeare, not yet 30, watches this scene play out for the first time on the stage of Newington Butts, near London Bridge.

Petruchio: Come, come, you wasp; i' faith, you are too angry.

Katharina: If I be waspish, best beware my sting.

Petruchio: My remedy is then, to pluck it out.

Katharina: Ay, if the fool could find it where it lies.

Petruchio: Who knows not where a wasp does wear his sting? In his tail.

Katharina: In his tongue.

Petruchio: Whose tongue?

Katharina: Yours, if you talk of tails: and so farewell.

Petruchio: What, with my tongue in your tail? Nay, come again, Good Kate; I am a gentleman.

Katharina: That I'll try.

[She strikes him]

Petruchio: I swear I'll cuff you if you strike again.

Katharina: So may you lose your arms.

The exchange seethes with a terrific comic tension, and the roars from the groundlings affirm for Will that he has a hit on his hands, a work that captures something essential and comic about the conflict between women and men. Though he has only a handful of plays to his name so far, Will imagines that this one is as likely to endure as anything he has penned.

Turn clockwise 410 years: Will's comedy is still winning roars from the crowd, and Mills and Gordon agree that a ballet version of The Taming of the Shrew would be a splendid project for Ballet Austin to develop for its next appearance at the Kennedy Center. Then Gordon adds, "And we'd like to commission the work from you." As Mills puts it, "They wanted to be a part of building the production from the ground up and partner with us." Surprised and delighted, Mills gets to work on Shakespeare No. 4.

Turn and turn and turn some more: Adaptation is a complicated process, especially when the source material seems so monumental. That prompted Mills to be very careful with the Bard initially -- "When I first did Midsummer, I approached it very reverently, spent a lot of time with the text, and got very deep inside it" -- but his approach has since loosened up somewhat. "Romeo and Juliet I knew inside and out," he says, "so I sort of stepped back from the text, because it can sometimes be a little overwhelming in its greatness. Like when we did The Rite of Spring, for me that music was so scary. People don't understand how a piece of music can be scary, but to die-hard musicians, you can completely mess it up. And I think the same can be true for the Shakespearean stories."

Coming to Shrew, Mills let his longtime love for and fascination with the performance style of commedia, in which Shakespeare rooted the play, lead him in the adaptation. Mills had in his mind a very broad style of performance and a light look to the production: No heavy drops and big arches -- the traditional look of Venice; he wanted players who "pick up their belongings, they move to a place, they open it up, and they do a show. They hang their curtains, they hang their own lights, they move their scenery, and they tell a story. That's how I was able to step back from the text a little bit."

In choosing music for his Shrew, Mills drew on the Italian baroque era. When it comes to selecting music, he says, "There's no fine science to it. I believe in picking good music that stands on its own and music that I like and that I think is danceable. I put it on a minidisc player, and I think about the scene, and I move things around. This ends in a minor key, this starts in a major key. Is that too big a shift? I may have 40 things on a disc that I'm shuffling around -- four or five pieces that may be appropriate, and I may settle on one. Kate's first entrance is very tempestuous, so you're not going to have a piece of adagio music with it. It needs to be fiery. So out of these 40 pieces of music, I may settle upon one, and then I just bring it into the studio and start to work. There's a lot of synchronicity to it. There's a lot of just throwing it up into the air and seeing what happens."

Rereading the play for the first time since high school, he was struck by the last scene in which Kate delivers her soliloquy about wives being subservient to their husbands. "I just got stuck there," Mills admits. "I felt really trapped. 'Okay, you agreed to do this. Now, what are you gonna do?' So I decided -- which is my prerogative -- that that wasn't the story I wanted to tell. I wanted to tell a story of a man and a woman of very different backgrounds, very different points of view, coming together to the center, to an understanding. She finds that he's not so bad, and he finds that she's not so spoiled. They come to a meeting place, as opposed to him forcing her into submission."

As he develops this idea, Mills comes up with a way to symbolize the turning point for Kate. He gives her a dream sequence in which she and Petruchio stand on opposite sides of the stage, and a rubber ball is rolled on from Petruchio's side to her side. "It's sort of the idea of one-upmanship," he suggests. "The ball's in your court, if you will." She stops it, something happens, she shoves the ball back to him. Something else happens, he sends it back to her, and slowly but surely the ball and the two characters move to the center.

Such symbolism proves key to Mills' choreographic translation of Shakespeare's ideas. "You can't do five acts of a play in a ballet," he says. "When we first did Hamlet, someone asked, 'Where is the "To be or not to be" soliloquy?' It's there, but it's not a dance. It's a metaphor. When Hamlet arrives at the end of the wedding, everybody leaves, and there's this coffin, and his father's body is in it. And for me that's the soliloquy. He has this tiny little dance, then [the coffin] disappears, and the father's eye appears. The father's watching everything that's taking place. So it's metaphoric more than literal."

Turn counterclockwise one week: The ballet is nearing completion, enough that Mills has a sense of what he has created -- and curiously enough, it plays off yet another adaptation of Shrew: the one Cole Porter dashed off in the 1950s. "Where Kiss Me Kate was a reconception of The Taming of the Shrew, I think what this production has turned out to be is a reconception of Kiss Me Kate. It's really vaudeville. It's really bright. And while it's not period, it's evocative of it, but contemporary, and that's what I like about it. It's like show business. That's what I wanted: to make it more like it's show biz, a big show -- a modern version of a touring company."

Turn clockwise toward the future: Mills has completed his fourth Shakespearean ballet. So when can we expect adaptations of the other 33 plays in the canon?

"I think probably this is it," says the choreographer. In fact, he says, "This may be it for me for full-length ballet for a while. This is the sixth or seventh one, so I'm ready to do something smaller and more intimate."

That may sound a disheartening note for those of us who have become fans of Mills' Shakespeare-ouettes. Still, he won't say never.

"I hadn't intended to do Shrew. I never even thought about Shrew," he offers. "But when the Kennedy Center calls, you don't say no." ![]()

Ballet Austin will perform The Taming of the Shrew Oct. 10-12 at Bass Concert Hall. For tickets, call 469-SHOW or visit www.balletaustin.org.