Crank Up the Machine!

Reviving the notorious masterpiece of a musical bad boy

By Jerry Young, Fri., April 25, 2003

Before Marilyn Manson, Ozzy Osbourne, and Alice Cooper, the bad boys of music were into the classics. Pick a decade and there's an eccentric composer who breaks rules and craves attention. Most mellow, some disappear, some we still know by their last names: Berlioz, Paganini, Liszt, Satie, Leo Ornstein, Stravinsky, George Antheil, John Cage.

Antheil held the title in the 1920s. On a European tour where he replaced a temperamental pianist, his habit of threatening audiences with a .32-caliber pistol got him noticed -- Victor Borge with a mean streak.

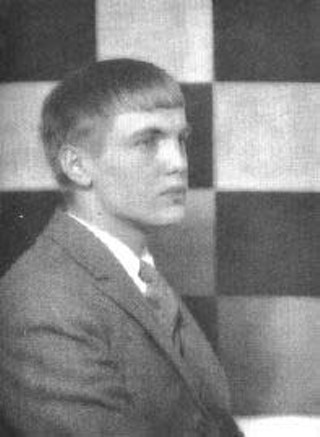

Born in Trenton, N.J., in 1900, Antheil was the post-World War I modernist's modernist. His "lost generation" fairy tale can't be told without dropping big names, which he does in his autobiography, Bad Boy of Music. In 1923 he lived above Sylvia Beach's legendary Paris bookstore Shakespeare and Company, became a regular at all the salons, and slept with his share of actresses, dancers, and a baroness. Picasso, Satie, Joyce, Yeats, Milhaud, and Leger cheered at his successfully scandalous 1923 piano recital of his Sonata Sauvage, Airplane Sonata, and Mechanisms. He succeeded retiring bad boy Stravinsky, who had forsaken the primitivism of the Rite of Spring and Les Noces for a less confrontational style. Man Ray captured Antheil's proto-Moe Howard pudding-bowl haircut for photographic posterity. Ezra Pound wrote a book, Antheil and the Treatise on Harmony, that treated the young composer as a visionary. Antheil wrote two violin sonatas for Pound's mistress, Olga Rudge, and threw in a drum part for Ezra.

His Ballet mécanique literally blew the wigs off Carnegie Hall concertgoers at its 1927 American premiere. Originally titled Message to Mars, Ballet mécanique called for a mechanical pianola, eight pianos, three xylophones, four bass drums, a tam-tam, electric bells, a siren, and three airplane propellers. Paris loved it in 1924. Antheil later tried to repeat the success in New York, upping the ante with additional pianos, but the machinery went out of control: The siren wouldn't stop wailing and the "propellers" -- actually electric fans -- which were pointed right at the audience, sent hats and hairpieces flying. This scandal flopped, and Antheil's career never recovered. After the fascinating 1933 piano work The Hundred Headless Woman, based on Max Ernst's collage engravings, Antheil's music relaxed into a romantic style you can hear in his score for The Pride and the Passion.

Despite hype and hubris, Ballet mécanique still charms. Austin Symphony conductor Peter Bay became fascinated with the work as an undergraduate. "It is kind of a novelty, but I loved the sonorities," Bay says. "I always wanted to perform it." The opportunity came when he was asked to conduct a UT New Music Ensemble concert. So, on Tuesday, April 29, Bay will conduct the Austin premiere of Ballet mécanique -- albeit the somewhat chastened 1953 revision that Antheil made for its first recording, slimmed down to four pianos, four xylophones, two electric bells, assorted percussion, and a recording of an airplane motor in place of the real thing. But you'll still be able to count on a powerful sound. ![]()

The UT New Music Ensemble performs Antheil's Ballet mécanique, along with works by Michael Dougherty, Lee Hyla, and Rob Deemer, on Tuesday, April 29, at Bates Recital Hall.