Bucky: A Spiritual Sales Pitch

Local Arts Reviews

Reviewed by Ada Calhoun, Fri., April 14, 2000

Bucky: A Spiritual Sales Pitch

Zachary Scott Theatre Center

Whisenhunt Arena Stage,

through April 22

Running Time: 1 hr, 40 min

At the close of this one-man show about the life and work of Buckminster Fuller, the title character gathers the whole audience onto the stage and instructs us to leave the theatre thinking of ways to serve mankind. My service will be the following warning: If you dislike audience participation, stay far away from this show.

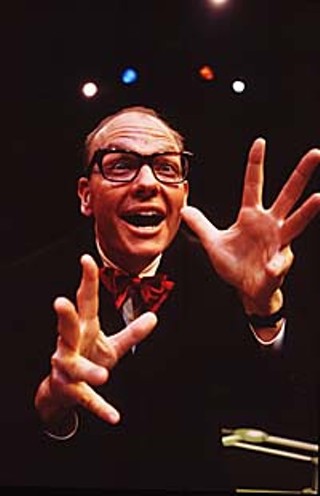

Moving on: Without knowing much about Buckminster Fuller the man -- past the facts that he created the geodesic dome, died in 1983, and retains a certain legendary status as a brilliant and eccentric inventor -- it is hard to judge the accuracy of the script by director/playwright Alice Wilson or the portrayal of the subject by actor Brad Armstrong. So let's put the biographical facts aside and look at Wilson's and Armstrong's Bucky as a character.

Bucky is a manic man who abstracts his world into various theories such as synergy and precession. He takes it all to absurd extremes, for example, expurgating the words "up" and "down" from his vocabulary because they're not true to the state of the rotating world, which has, after all, merely "in" and "out." Armstrong excellently portrays Bucky's intellectualism via a distracted, flurried aura, intermingled with wistful observations. This doesn't, however, mean that Armstrong is inherently appealing as a presence, especially when he's acting like some walking, talking Census 2000 (the long form) and plying the audience with great familiarity for answers to his many questions.

Which brings us to audience participation. To demonstrate the validity of Bucky's aforementioned views on preposition-choice, the audience is led in an exercise in which everyone raises their arms up, then down, then makes motions of reaching in and out, repeats with closed eyes, then talks about it. At another point, Bucky has audience members mime holding opposite ends of a rope. Later, everyone is called onto the stage to dance to the Beach Boys while chanting "yes" and then "no." After intermission, a discussion about the dance is held, observations like "I felt connected" are bandied about, and Bucky offers his opinion that the word "no" keeps us from attaining our true potential.

The program lists Wilson's day job as a corporate trainer for companies like Motorola, and this show does have the ring of a "we're a team; go team!" motivational speech, right down to the comforting clichés about achieving success despite being "...kicked out of Harvard. Twice." Thrown into the aesthetic mix are elements of an economics lecture (Fuller was adamant that Malthus was wrong and that it was indeed possible to feed the whole world), a physics class (slides, demonstrations, and all), and a spiritual sales pitch laced with lines such as "You do not belong to you; you belong to the universe."

Certain sensibilities will adore everything from the dancing and discussion to the universalist rhetoric and plentiful visual aids projected on overhead screens. Many people will revel in the opportunity to offer comments like "Saying 'yes' while dancing felt ecstatic" aloud. But for anyone who recoils at New Age jargon, cheaply sentimental stories (Bucky's dead daughter is invoked), or feel-good pep talks, and certainly anyone who believes in the blessed virtue of the fourth wall, Bucky is an instance in which a strong case could be made for invoking the forbidden word "no."