The Human Condition

Ex Machina writer/director Alex Garland on robots, sex, and the collaborative spirit

By Cindy Widner, Fri., March 13, 2015

Alex Garland isn't a big fan of auteur theory. Despite having penned lauded screenplays with heaps of distinctive style (28 Days Later, Dredd, Never Let Me Go), Garland only recently jumped to the director's chair with Ex Machina, making its North American premiere at SXSW 2015. Glowing reviews in Europe and stateside hype aside, Garland maintains that his leap to director is no big deal.

In fact, to assume that his directorial debut represents some sort of artistic or career advancement, he says via telephone from London, "comes from the idea that there's something about directing which is different from everything else on a film. In my experience, filmmaking is a group of people just working together to make a film that everyone agreed to make. In that respect, there wasn't anything significantly different on this film from any of the previous films I've worked on. So although it looks from the outside like this big epiphany, it just didn't feel like that to me."

"It's pretty hard to convince me that filmmaking is not a collaborative creative enterprise, because, empirically, I can see that it is," he added when queried about the auteur thing. "Honestly, it's the collaboration that I find fun and enjoyable, so not only am I not an auteur, I'm not very interested in it."

Garland's generous and probably sort-of accurate characterization of himself as just another creative laborer in the film mines is both bolstered and undermined by the distinctive qualities of the movies he's written – they are consistently visually rich, slightly futuristic, and dense with atmospheric menace – no matter who directs them. For that, he credits the "fantastic cinematographers" he's worked with, along with the influence of his father, a cartoonist. "I grew up reading comic books," he said, "which function like storyboards, which in turn function like films."

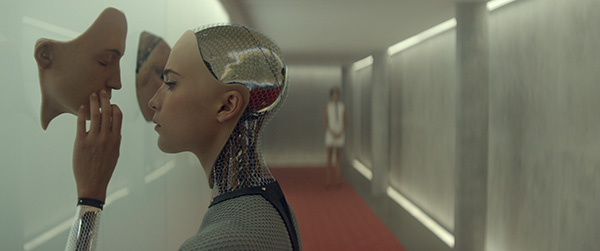

If, in the tradition of Spike Lee, we are to refer to Ex Machina as an Alex Garland "joint," then it should be noted that it's a remarkably crafted collaboration. The film, which Garland also wrote, is set almost entirely in the remote, rustic-modern abode/headquarters of reclusive Internet billionaire and genius Nathan Bateman (Oscar Isaac), who has brought contest-winning programmer Caleb Smith (Domhnall Gleeson) to help him out with a little experiment he's been conducting in his fortress of solitude: the creation of human-shaped robots endowed with artificial intelligence. It's to be Caleb's task to participate in a Turing Test – a method, created by AI pioneer Alan Turing (see: The Imitation Game), of determining whether a machine can behave in a way that's judged as human. The test subject is the robot Ava (Alicia Vikander), who takes the form of a comely human woman – though she is still, literally, transparently a machine.

Minimalist, cutting-edge, and secretive, Nathan's lair evokes the quiet, smooth-surfaced menace of a Kubrick film – specifically 2001: A Space Odyssey – though the source of the suspense, and possible danger, isn't clear. In its subterranean simplicity and Zen-calm quietude, the place exudes expensive tech taste – a mood achieved, along with some stunning visual effects, on a relatively tiny budget.

"We knew this film was going to require a very large visual effects element," says Garland. "We knew we had to compete in a way with any kind of big-budget, mainstream movie if we were going to carry it. There's a whole bunch of things you can do to try to achieve that within the budget. But the main thing you do is you shoot it really, really fast. So we gave ourselves a six-week shoot, and the money we saved by doing a quick shoot you put into postproduction."

The subtle set and seamless effects allow characters and dialogue to be foregrounded. Isaac's Nathan is equal parts Conrad's Kurtz ("In a metaphorical sense, he's spent a lot of time upriver," says Garland), damaged nerd-boy, and manipulative bully who is "fictionalizing a version of what they actually are," says the director. "He deliberately presents himself to the other male character as someone who is a bit dangerous and a bit mercurial, predatory, and sinister, in order to encourage this young guy to feel that he needs to save this female-appearing robot from him. And it is actually contained in him to a degree. But the degrees may be varied."

About that damsel in distress. It could be said that Ex Machina is as much about gender as it is about technology – or, more accurately, the intersection of the two. As much as it mulls the concepts of humanity, mortality, and godliness (though, frankly, Nathan and Caleb make for some piss-poor godheads, if that's what they're going for), Garland's film puts front and center the slippery notions of gender, sexuality, and power. Ava (so named because "calling her 'Eve' would have been too prosaic," says Garland) takes the form of a beautiful woman whose sexuality is a crucial part of her passing the test.

And yet, as Garland puts it, "there are no women in the film. And right in the middle of the film, there is a conversation about the fact that Ava doesn't actually have a gender. She only apparently has a gender." Paralleling that disruption is Caleb's questioning Nathan about why sexuality has to be a component of humanity. Nathan's answer is wonderfully flippant – "Why else would we do anything?" – but Garland is more straightforward: "Sexuality is a component part, it seems, of consciousness."

Whether Ex Machina disrupts the male gaze and dismantles gender tropes while offering up a healthy ration of lovely naked ladies to look at will be a matter of debate. For Garland's part, he's on to other concerns. "I get very bored with the director-centric stuff," he says. "I do want to acknowledge how much this film is the people I work with."

"There's a moment in Ex Machina where Ava is wearing a white dress," he elaborates, "and she walks past the Gustav Klimt painting of a woman in a white dress – a portrait of [the sister of Ludwig] Wittgenstein, a philosopher referenced repeatedly in the film. What that would look like is a very clever bit of directing – of textural, narrative, philosophical complexity. It would completely get attributed to me, and I literally had nothing to do with it. I did not know Miche [Michelle Day, longtime set decorator] had put that painting on the wall until I walked on the set. And just to be clear about it, I've seen directors take the credit for that kind of thing. That's why I don't like auteurism as a principle – because I know what Miche did."

Headliners, North American Premiere

EX MachinaSaturday, March 14, 8pm, Paramount

Friday, March 20, 9:15pm, Topfer