A Martyr's Epitaph

The Texas Documentary Tour presents Rob Epstein's 'The Times of Harvey Milk'

By Anne S. Lewis, Fri., April 8, 2005

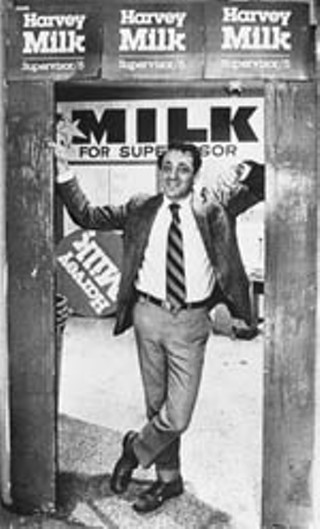

The Oscar-winning documentary The Times of Harvey Milk (1984) chronicles the cultural clash between San Francisco's gays and their would-be demonizers back in the Seventies. This clash would culminate in the slayings of City Council member Milk, the city's first openly gay public officeholder, and its mayor, George Moscone, by fellow Council member Dan White, a former fireman and cop. Watching this film 27 years after the events it portrays, one is struck by its feeling of timelessness, probably because the Harvey Milk story is the past, present, and future of the gay struggle for co-existence across the country. Even though San Francisco and its City Hall – today the emblematic, renegade first to issue marriage licenses to gay couples – have come a long way from the initiative to bar gay teachers from public schools that galvanized Milk's political career, there are plenty of locales between the two coasts ripe, today, for Harvey Milk scenarios.

Director Rob Epstein (The Celluloid Closet, Common Threads: Stories From the Quilt) takes us through Milk's grassroots political organizing and eventual election, through the murders and the breathtaking visual eloquence of the candlelit memorial that drew tens of thousands of San Franciscans on the evening of the assassinations, contrasted with the uncontrolled fury of the mobs who stormed City Hall, breaking windows and torching police cars, when White's lenient verdict and minimal sentence were announced. Despite what would have seemed airtight evidence of premeditation, White was convicted not of double homicide but of voluntary manslaughter.

The film, made five years after the events it chronicles, is narrated by Harvey Fierstein and told through the use of archival news footage and the talking-head recollections and later commentary of eight for whom Milk's political presence had varying impact, including a car mechanic and union delegate whose first thought when he learned that Milk was gay was how to break it to the guys at the union that they'd voted "to support a fruit." The blow was softened, he said, when they found out that it was Milk who'd gotten all the Coors beer out of the city's gay bars. The strange bedfellows of political coalitions.

Austin Chronicle: What was it about Milk that attracted your interest?

Rob Epstein: In the mid-Seventies, I lived in San Francisco and knew Harvey Milk as a neighborhood shopkeeper. Back then, the Castro neighborhood, where I lived, had a villagelike feeling to it with all the shops owned and run by locals. And there was Harvey with his camera shop, which is where I took my film to be developed. Harvey made it his business to know every person who walked through his door. One day I remember he made some outrageous sexual comment to me which caught me off guard, and which of course he loved to do. But when I began to take note of him as a leader and something more than a politician was in the fall of 1978 during the anti-gay ballot measure on the California ballot dubbed the "Briggs Initiative," which was an attempt to ban gay school teachers and their supporters from working in the public schools. This was a very big fight back then – as it still would be today. I had started a film about this campaign, the first in a series of conflicts of values. Harvey Milk was recently elected to the City Council and he stepped up to the plate debating state Sen. John Briggs (author of the proposed legislation) up and down the state. Weeks after the election and the defeat of the initiative, Harvey was shot and killed. The focus of my film changed, or rather expanded.

AC: What were some of the challenges that you faced in making the film?

RE: The biggest challenge in making the film was convincing funders that this wasn't just a local, provincial passing news item. But probably the biggest creative challenge was that we were telling the story in retrospect, years after the events. I wanted the film to have the immediacy of a cinema vérité film, as if the events were unfolding in real time, but we were filming the interviews five years later. In effect, it's an historical film made like a verité story. The Times of Harvey Milk is a bit of a hybrid. This wasn't easy to make work.

AC: The film has won so many awards and been screened all over the world. Were there any unusual audience reactions?

RE: In 1990, just before the Soviet Union fell, The Times of Harvey Milk was invited to be part of a tour of American films in the USSR. The tour went to just about every region, and I traveled along with it to some. One screening I attended was in Irkukst, the capital of Siberia. The event was billed as simply a tour of "American films." I'm sure the people of Irkukst were expecting Star Wars, not a documentary from San Francisco with a gay protagonist. The screening took place in a huge auditorium about the size of Lincoln Center, and it was packed. Since the film wasn't dubbed or subtitled, the entire transcript of the film was read by one old man droning on in a monotone. But the audience was rapt and stayed with it. At the end of the film, one person stood up and said something to the effect of "How could you make such a film without any moral message? Would you make such a film about a prostitute?" And then, in response, another person stood up and shouted, "This is a film about democracy! We should only have such a conversation in this audience tonight."

From there, it got increasingly more heated, with the audience arguing among themselves, so at a certain point we were told by the tour organizer that our van was ready to go, that the motor was running, and that we should make an immediate departure. A year later the Soviet Union fell. Go figure.

AC: How do you feel as you watch a film that you made 21 years ago? Has your style of doc-making changed since then?

RE: Watching the film today floods me with all sorts of memories and emotions. Part of my response to the film is very personal and very much about the experience of its making. Another part of my response is thinking about all that has transpired between then and now. It's an ambivalent relationship we all must feel when the passing time is made evident. But mostly I feel proud that the story and content continues to resonate. Here we are fighting the same battles again and again. But the bottom line is that it still plays well as a film, and Harvey lives in this movie.

As for my filmmaking style, it's probably evolved some. Stylistically, I enjoy both following stories as they happen as well as finding and creating the material to construct a story after the fact. Now, I am doing another historical documentary, the subject being Allen Ginsberg's poem "Howl." We're attempting a different approach.

AC: If you were to make this film today, would you make it the same way as you did in '84?

RE: I think I would still take the same approach today. I had decided early on to tell Harvey's story with only a few representative people rather than a survey approach with a bunch of people coming on screen only to make points. In the film there are eight people who appear on camera, chosen from about 75 research interviews, each of whom represents an aspect of Harvey's legacy. In the end, I think this was one of the film's strengths, since each of them functions as characters in the film, as well as telling an aspect of Harvey's story.

AC: Having watched the film on the more recently released DVD, I had the benefit of watching "the alternative ending" segment, an outtake of the aforementioned car mechanic, (who discovers that Milk is gay after his union has voted to support him) telling the story of how (long after the assassinations) his own daughter came out to the family, a revelation he was proudly able to handle with enlightened aplomb. How come that ending didn't make the final cut?

RE: While we were editing the film, for the longest time this passage was in, and then it was out, and then back in again. Finally I decided to leave it out because I didn't want it to appear as if [the mechanic] had a vested interest in the issue, when in fact he found out his daughter was gay after Harvey Milk was killed and had already gone through his own rethinking. Thankfully, a DVD edition allows for the possibility of retrieving those little gems. ![]()

The Times of Harvey Milk screens as part of the Texas Documentary Tour on Wednesday, April 13, 7pm, at the Alamo Drafthouse Downtown. Rob Epstein will conduct a Q&A after the screening. Tickets are $4 for current Austin Film Society members and new members joining before the screening, as well as students, and $6 for nonmembers. They are available through the Austin Film Society (www.austinfilm.org) or at the venue one hour prior to screening.