The Stuff That Dreams Are Made Of

Linklater and Company Get Animated with "Waking Life"

By Marjorie Baumgarten, Fri., Oct. 26, 2001

Richard Linklater is on the stage of Austin's Paramount Theatre introducing his new animated movie Waking Life before the hometown audience. Linklater, now with eight movies under his belt, always looks forward to these Paramount premieres, tonight more than ever, since one of the key scenes of the movie (dubbed the "Holy Moment") is set inside this theatre. He welcomes instances like these: life imitating art imitating life. In fact, philosophical ruminations and life's big unanswerable questions are the real subject matter of Waking Life -- or rather, the asking of questions is the movie's objective, not necessarily the provision of answers. Linklater explains to the audience as he exits the stage, "Most movies strive to be a four- or five-course meal. Waking Life strives to be a pot brownie."

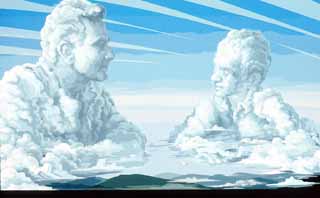

The metaphor is apt. An animated dreamscape in which one central character (played by Dazed and Confused's Wiley Wiggins) and a host of cameo players all quest for answers to life's eternal mysteries, Waking Life wants to feed your head -- with ideas, laughs, oohs, and ahs. But this cinematic caprice is also a homegrown affair, an autumn harvest brought to market by a team of local cultivators. Linklater, whose film Slacker catapulted him into the modern pantheon of independent filmmaking in 1991, may be the orchestrating name above the Waking Life title, but this project is truly the creation of many dozens of authors. A uniquely collaborative work, Waking Life is an amalgam of many voices and contributions. The story of how it all came together is a story about process, the process through which a marriage of reality and unreality found a happy medium.

The narrative for Waking Life came from an idea for a movie that Linklater had been thinking about for more than 10 years. It was to be a movie about abstract ideas, our human constructs of reality, and Linklater's interest in the technique of "lucid dreaming," a process by which individuals can become aware of the fact that they are dreaming and consciously alter the course of events in that dream state. But, he says, "it never quite worked in my head because I was seeing it live-action." It was not until Linklater saw the animated shorts "Roadhead" and "Snack and Drink" by Bob Sabiston and Tommy Pallotta that he began to see the possibilities of merging his dream movie with the documentary-like breakthroughs in animation that their work had accomplished.

Pallotta is a figure long known to Linklater, having worked on the crew of Slacker, in which he also appears in a brief role. After studying philosophy and filmmaking at UT, Pallotta went on to direct the feature film High Road in Austin in 1996. Sabiston, an artist and a computer-programming whiz, is one of those rare creatures in whom left-brain and right-brain thinking form a balanced and mutually beneficial alliance. A graduate of the famed MIT Media Lab, Sabiston's award-winning animation ("Grinning Evil Death," "God's Little Monkey") earned him fans and admirers, among them some of the folks at MTV. Pixar, the groundbreaking animation studio, also came calling with an invitation to work on Toy Story, but by that time Sabiston had decided that the world of corporate animation was not for him. He turned down Pixar's offer (it was, in fact, the second time Sabiston had personally said no to Steven Jobs) since he had already decided to move to Austin, partially because, self-admittedly, he was a "really big fan of Slacker."

During a sojourn back to New York, where Pallotta had since set down roots, Sabiston collaborated with Pallotta on a series of 30 interstitials for MTV using drawing software that Sabiston had created. His software is similar to rotoscoping, an old animation technique in which live-action film frames are blown up and traced by hand, rendering a fluid, lifelike look. Sabiston's computer-approach allows the animator to draw or trace objects on peripheral Wacom tablets while his software interpolates some of the in-between frames. The work is still painstaking, but is not nearly as slow-moving as the old rotoscoping methods. With each project he does, Sabiston refines and improves his core software. However, he quickly adds, "Really all the computer stuff I do is geared toward the visual arts. I'm very interested in computer programming but pretty much only in the context of computer graphics and the visual aspects."

Sabiston and Pallotta experimented with the technique on their next independent project "Roadhead." During a road trip back to Austin the duo shot a series of interviews, which Sabiston then rendered into an animated short, with the help of a team of volunteer local artists, who he taught to use his software. Next came "Snack and Drink," a three-minute short about an autistic boy in an Austin convenience store, and Figures of Speech, a PBS television series. "Snack and Drink" has received the rare honor of being selected to become part of the permanent collection of the New York Museum of Modern Art.

Linklater had been following the progression of Sabiston and Pallotta's work with enthusiasm. In fact, he provided space at Detour Filmproduction, his Austin production office, for them to set up the numerous work stations they needed to complete Figures of Speech. While looking at Sabiston and Pallotta's new work, it just clicked. Says Linklater, "That's when I started thinking, 'Oh, that old idea that's been swimming around in the back of my head: That's the way it should look.' It was just an instinctual marriage in the mind."

Suddenly grasping the potential for this expressively hand-rendered animation to provide the engaging visual balance for his heady, run-on ruminations, Linklater says the project immediately moved forward. "Bob could have done anything he wanted at this point with his software," notes Linklater. "He could do a TV show, or a traditional animated film, but he was much more interested in the story and the characters. When I talked with him about doing this 'narrative that has a story but the lead character disappears for times and it's kind of his perspective but it's not,' Bob was, like, 'Oh yeah, cool.' I think he knew what we all knew: that it wouldn't work as live-action."

From this point, the collaborations began fanning out. Linklater's idea was to quickly shoot the original footage for the film with hand-held digital video cameras that he and Pallotta operated. With only a four-person crew, they shot (predominantly in Austin) Wiggins walking the streets, sometimes flying, and witnessing and engaging in thought-provoking conversations with the likes of Timothy "Speed" Levitch (the subject of the documentary The Cruise), Ethan Hawke, local non-actors, and Linklater himself. As for finding his eclectic, largely nonprofessional cast of oddballs and dreamers who spout theories and ideas with the speed and refinement of mental spitballs, Linklater again trusted his instincts.

"I reached out into the world and found these people who I thought were on the wavelength," he explains. "So many of them wrote their own dialogues or I worked with them on scenes. In a full third of the scenes, all that information comes from the person saying it. Another third is probably something I wrote, which they rewrote during rehearsals, kind of making it work as a scene. Then another part was pre-existing text. The film is an amalgam of a lot of ideas, it's very much kitchen-sink. In a film of ideas, that's really the narrative. It didn't have to fit into a narrative as much as it had to be just on the wavelength of it." (However, naysayers of this laid-back approach, such as The New Yorker's Anthony Lane, have accused Waking Life of seeming as though it were filmed in "Slackerama.")

Due to the film's collaborative performance style, Linklater admits to his nagging discomfort regarding this film's "written and directed by" credit. "The Writers Guild, the fucking union, made me take off my original notations. I had, 'script by me and additional dialogue by various cast,' which would be the accurate thing, but they made me take that last part off. It's some kind of union thing. So, I'm slightly embarrassed by the 'written and directed by.' Like I wrote every word of it or something. It's so not the point."

The team's initial DV footage would eventually be whittled down to its 97-minute running length by Linklater's longtime editor Sandra Adair. The final cut was then used as the template for the animators to come in and do their stuff. It was in that animation stage that Linklater's vision of a dream state was truly realized.

"Let's face it, none of the material in this movie has any business being in a film, hardly any of it," Linklater admits ruefully. "It needed that level of unreality. And I don't think traditional animation would have worked, although it would have been a little better [than live-action]. But it wouldn't have worked the way this does because this begs the question about reality, because it is reality in a way. It sounds real, has real gestures, real people. I like the way it kicks your brain into overdrive. It's a perfect marriage of content and form that we've all agreed we'll probably never find again -- in the animated terms. It was just too perfect. The questions of reality and unreality, the questions of the animation, so many of the themes about individuality and identity -- the form of the animation sort of touches on that in a lot of ways."

The revolutionary animation came from a crew of 30 artists, assembled in staggered shifts around 15 work stations at Detour. The goal was for each animator to turn out 14 seconds of work each week. The process took an entire year. Sabiston's experience on his short films had taught him to look for artists to whom he could teach the use of his software rather than computer wonks. "That's the genius of Bob's software," says Linklater. "Fundamentally, it's just a new way to paint."

As the art director, Sabiston oversaw this whole phase of the process. He describes its evolution as follows: "First, we all sat down and watched the film on video and then talked about it. About that time I had the movie transferred to QuickTime so that people could draw on top of scenes. I had everyone pick the scene they liked the most and show how they would draw it. And then we'd look at them all. A couple people would pick the same scenes and then we'd have to choose one person. Everyone started out with an initial character. As people finished, I reassigned them to other areas.

"Rick was pretty open-minded about how the scenes looked. They had so many different looks, and that's what he wanted. It was only in the case that someone just didn't look like themselves, or the animation didn't look like the actors, or didn't capture whatever he liked about the actors, that we asked the person to change what they were doing." Linklater concurs: "That's what it was always about: the diversity of styles. I just love the idea of a hand-held animated film with all these different styles. Most animation feels like there's one designer and everything looks the same." Although Waking Life has a unified look as it passes before the eyes of a first-time viewer, repeated viewings or perusals of still frames will uncover the wealth of diversity in the individual styles of the 30 animators. A visit to the movie's nifty Web site (www.wakinglifemovie.com) provides still images for viewing as well as a gallery showcase of many of the animators' non-Waking Life-related paintings. (Don't forget to take a peek at the onsite trailer while there. It's a knockout.)

Linklater's indulgence of personal style also applied to the movie's soundtrack: a score by Glover Gill and performed by Austin's Tosca Tango Orchestra. "In the last few years I became a big Tosca fan," he explains. "I thought they were kind of genius in their own way. So when I was thinking about this movie, I remember going to one of their shows and just thinking, 'OK, the way that tango music can be kind of airy and upbeat, and then it can just turn and some little refrain can get creepy, or the mood switches -- that's just perfect. It's one of those things, you never really question it. But I love the idea of them actually being in the movie. I like that scene in the beginning with them practicing a piece. It kicks off the idea that the movie is really about process. There's a great thing Glover says there. He wants one of the musicians to be slightly less perfect. 'Can you be a little wavy, maybe, due to being slightly out of tune?' And I thought, 'Oh, that's perfect,' because our goal certainly wasn't perfection, it was just process."

Ten years ago Linklater launched Slacker into the world and that movie's depiction of the social disconnectedness experienced among young inquiring minds touched upon something timely and evocative within our culture. Now 10 years older, Linklater returns with probably the first computer-animated, independent feature film (which for all the state-of-the-artness that designation implies, Waking Life is about as low-tech as a film can be, having been created from beginning to end with consumer-grade digital equipment and Macintosh G4s), and in many ways Waking Life resembles that earlier film. The movie's opening scenes are an homage to Slacker and the many roads not taken. Characters from some of Linklater's other movies make reprise appearances during Waking Life. Yet with this new project, Linklater has turned some of his attention to connectedness and collaboration. Waking Life is all about tracing how our individual brains function and make meaning. As Waking Life demonstrates, this is both a personal and communal experience. ![]()

Waking Life opens in Austin theatres on Friday. See Film Listings for review and showtimes.