A Full Color Palette

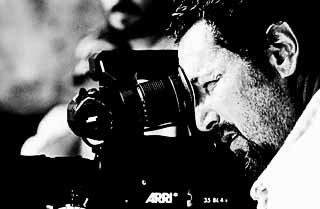

Painter-Director Julian Schnabel's 'Before Night Falls'

By Sidney Moody, Fri., Feb. 9, 2001

Julian Schnabel is a rare hybrid: a painter-director. Perhaps it shouldn't be this way. Cinema is, after all, primarily a visual medium that draws heavily on painting and the history of art for its effects. But Schnabel makes it look easier than it actually is. David Salle and Robert Longo, painter-directors who came from the same New York art world explosion in the Eighties, have each made a film that was a critical and commercial disaster (Search and Destroy and Johnny Mnemonic, respectively). Schnabel's own first film Basquiat (1996), about the rise and fall of the graffiti artist-cum-painter Jean Michel Basquiat, could be considered at least a modest success in comparison. But now Schnabel has accomplished the enviable task of making a movie -- his second -- that a lot of people are excited about: Before Night Falls. The painter-director concept suddenly looks like an idea whose time has come.

Before Night Falls, selectively based on the memoir of Cuban author Reinaldo Arenas, begins as a visually dense coming-of-age tale in pre-revolutionary Cuba and then shapeshifts into a searing political thriller. (The title refers to Arenas writing while on the lam and trying to get as much as possible written before darkness fell.) The openly homosexual Arenas ran afoul of the authorities and was imprisoned on trumped-up charges of corrupting minors, of which he was eventually acquitted. But as his case filtered through the Kafka-esque Cuban bureaucracy, it evolved into a more specific persecution of Arenas as a writer -- the authorities were infuriated by his ability to smuggle his writings out of the country to be published in France and by his sexual bent in general. According to his memoir, Arenas was arrested on a number of sexually related charges but was acquitted each time the case went to court. But the memoir also makes clear that, for Arenas, the entire universe was a sexual organ for which he was the priapic agent -- and he humps dogs, donkeys, trees, dirt, rain, rivers, and even the Caribbean Ocean. In fact, water is a central element of Arenas' poetic world, and Schnabel's film is filled with so many cosmic ejaculations of gushing water that it practically splashes off the screen. And Arenas' ethos of sexuality was so connected to his sense of freedom that he refused to have sex during his years as an inmate in the infamous El Moro prison. Arenas was finally able to scam his way out of Cuba during the Mariel boat lift in 1980. He ended up in New York, where he contracted AIDS and eventually took his own life in 1990, blaming Fidel Castro for the events and situations that led to his demise. Schnabel, searching for a project to work on after Basquiat, got the rights to shoot the film from Arenas' literary heir Lázaro Gómez Carriles. (This is not the first time Schnabel has singled out an obscure artist and brought them recognition. As is well known in the art world, Schnabel arranged for Captain Beefheart -- aka Don Van Vliet -- to get a market for his art work when his musical career stalled, thus allowing Vliet a measure of economic stability that had for so long eluded him.)

Schnabel pulled a coup of sorts when he snagged mega-star Spanish actor Javier Bardem for the role of Arenas from teenager to adult. Although virtually unknown here (with the exception of a role in Pedro Almodóvar's Live Flesh), Bardem is certain to become a familiar face to American audiences. Bearing a remarkable resemblance to Arenas, Bardem gets inside the head of this writer who describes himself -- and other writers as well -- as "strange, abnormal beings." But the actor almost passed on the film altogether. Bardem has an uncle who held a prominent position in the Communist Party in Spain, and it was a struggle for him to decide to take the role. He did, though, and Bardem, who comes from a family of performers and movie directors, reveals himself to be an inventive actor who latches on to the tiniest gesture as a way of conveying his inner state. When Arenas rents his first apartment in Havana, Bardem grabs onto a set of keys with his teeth and gleefully shakes his head.

As impressive as Bardem is, Schnabel never lets us forget that he is the real star of this movie. He utilizes a full palette of cinematic techniques: swooping tracking shots, hand-held cameras, jump cuts, lovely montages arranged to voiceovers of Arenas' poetry, various film stocks, documentary footage, dream sequences, frantic POV shots, etc. Schnabel seems to be trying very hard to be taken seriously as a filmmaker, and the Grand Jury Prize that Before Night Falls won at the Venice Film Festival, as well as the Best Actor prize that went to Bardem, would indicate that his efforts are not in vain. The Austin Chronicle recently spoke to Schnabel by phone from his studio in Manhattan.

Austin Chronicle: There are some scenes and characters in the movie that are not in the memoir. For example, the scene in the beginning of the film in which the schoolteacher tells the Arenas family that Reinaldo has a gift for poetry and then the grandfather grabs an axe and starts chopping down a tree, or the scene with the transvestite Bon Bon played by Johnny Depp, who then plays Lieutenant Victor ...

Julian Schnabel: This movie is not an illustration of the book. It's an accumulation of lots of Arenas' writings and stories and things that Lázaro [Gómez Carilles, Arenas' close friend and the film's co-screenwriter] told me. The thing about the teacher and all that -- in Arenas' book Singing in the Well, his grandfather chops down the trees where Celestino is writing on the trees. Later, in The Hallucinations, Fray Servando [an Inquisition-era friar who appears in several Arenas novels] is being chased all over Mexico, the hatchets get traded in for chains. This is the story of a guy who was chased all of his life. His grandfather was the form of censorship in Singing in the Well. What was the other one?

AC: The two Johnny Depp parts [Bon Bon, a drag queen in prison, and Lieutenant Victor].

JS: In The Color of Summer there's a description of Bon Bon. In a sense, Arenas rewrote his story many times, and so in The Color of Summer, Bon Bon and Lieutenant Victor are both characters in that book. But in many of his books, one person can be many different characters. It's a real Reinaldo Arenasism to kind of have one person be different sexual kind of genders or be more than one person. I took the liberty to turn Bon Bon into the same character as Lieutenant Victor because if the island is a penitentiary to Reinaldo the idea that State Security would go to such Byzantine lengths to undermine the stability of prisoners -- like, where is the guy going to get such fancy gear and a great wig like that? You either give a lot of sexual favors -- or you run the prison. And the fact that the guy who is, in a sense, the key to freedom -- to getting his manuscripts over the walls -- would be the same person who has the foot on the back of his neck is kind of an interesting dynamic. There are many things that are not in the book. All the speeches of Castro are something that Cunningham O'Keefe went over to find the right things where Castro basically is judged by his own words. The thing with the balloon -- a balloon never sailed through the convent of Santa Clara. But in the writing of "The Parade Ends," when Arenas talks about like he's floating and everything comes to him with that incessant tap tap -- that suggested to me the notion of floating. And there's an expression in Cuba where they say, "Oh, he left just like Jesus Mateo." And that means that the guy disappeared on a balloon and never showed up again. But what I'm saying to you is that it's like an allegory or an emblematic image, and the fact is that the guy would take off in the balloon, thinking he's going to make it and fall short and land on the Malecon seawall. I just thought it was an interesting touch. Besides the fact that I loved the movie Andrei Rublev by Tarkovsky. But later, after making the movie, I was looking through The Color of Summer, and Arenas wrote: "I dreamed I had a balloon that sailed from the grackles in Lenin Park and went farther and farther away." So through anterior agreement, there's a ton of stuff that pops up where we are totally in sync with each other.

AC: You've expressed your admiration for Pasolini's first film Accattone. And I can see some similarities between that film and both of your films. And in Before Night Falls, there are some echoes of Pasolini's last film Sal. Would you care to comment on this influence?

JS: I never thought about Sal when I was making this movie, even although I think that it's a really interesting movie. What did you think -- when they were in the convent?

AC: Mainly the Lieutenant Victor/Johnny Depp interrogation scene with its fusion of sexuality and totalitarian power.

JS: I didn't think so literally about that. But I think that, basically, Pasolini's sensibility is something that is kind of -- we have a similarity in a sense, so I don't think you're wrong there. I think the movie to do with The Battle of Algiers by Gillo Pontecorvo. But I think also, certainly, there's a kind of sense of a documentary kind of feeling of the film and also the kind of different levels of voice kind of feels like a Pasolini film in a way.

AC: The cameos of Sean Penn and Johnny Depp have been much commented on. But the cameos of film directors Hector Babenco and Jerzy Skolimowski [whose 1967 movie Hands Up! was blacklisted by the communist regime in Poland] and the cameo of character actor Michael Wincott [who also appeared in Basquiat] have been hardly mentioned. Would you care to comment on them?

JS: I love all of those people. Every one of them came and really brought with them their work, which is great. I loved [Hector Babenco's 1981 movie] Pixote. Hector loved Before Night Falls. Hector said he thought it was the greatest Latin American film on the subject of freedom. And that a Jew from New York would make it is a miracle to him. And that's interesting. Jerzy's father was killed by the Nazis. He's not Jewish, but he had built the subway system in Poland, and he fought against the Nazis. Everybody in some way has been involved in some kind of fight for freedom in some sort of way. Then Michael Wincott is a very close friend of mine, and it's a very difficult role. I based it on the trial of General Ochoa and the purging of Herberto Padilla. It's a kind of compilation of these two things, and it's also sort of a construction of mine, because certainly they didn't have live television at that time. But they did record the trial of Ochoa, which is shocking to see if you ever get a chance to see it. But Michael Wincott really gives a masterful performance there. And I think everyone's good. My wife is incredible as his mother. And Vito did a good job -- that's my son. [Vito plays Arenas as an adolescent.]

AC: Your daughter Stella had a very brief scene.

JS: All of my kids are in the movie. My parents are in the movie.

AC: Hector Babenco's portrayal of the dissident writer Virgilio Piñera --

JS: And the other thing about Jerzy and Hector -- I love Hector -- having them around the set is a nice thing. Dennis Hopper came down to visit. It just adds a kind of feeling of auspiciousness and sensitivity, you know?

AC: Touching on Piñera. He wrote a novel in which he describes a valuable pearl which is later found to be worthless and is flushed down the toilet. The name of the pearl is an anagram for "Fidel." Is there anything in Arenas' writings where he covertly or overtly attacked Fidel Castro?

JS: Yes. You should read The Color of Summer. He didn't at the time when he was censored. This was later -- if you see what he said in "The Parade Begins," the optimism in that poem is written 20 years before "The Parade Ends," which is the end of the movie. In The Color of Summer, he talks about "The Seven Wonders of Cuban Socialism" [see sidebar, this page]. He also talks about "Thoughts on Hell," which are pretty damn interesting. You should look at The Color of Summer, because it's the last one that was published, and the others are more metaphoric.

AC: The movie states that Arenas is counter-revolutionary, because he is a natural-born writer. But there are a number of celebrated Latin American authors -- Gabriel García Márquez being one of them -- who have a Marxist orientation and therefore, obviously are not counter-revolutionary. Márquez, as is well-known, is friends with Castro and is mentioned several times in Arenas' memoir, mostly unfavorably. What do you think Márquez's reactions would be if he were watching Before Night Falls in the same room with Castro?

JS: What do I think his reaction would be? Well, first of all, I don't think that Reinaldo liked Márquez. And one of his things in The Color of Summer is that every time you want to insult somebody you could say he's the most vile person after Gabriel García "Markoff." It depends on probably the separation of what Márquez thinks of Reinaldo's writings and what he thinks of Reinaldo's politics. Obviously, politically they absolutely disagreed. I think that García Márquez has had a very special position with Fidel Castro. He's not Cuban, and he didn't have to come up through that system. What do I think his response would be? I don't care what his response would be, frankly. I mean, who gives a shit about him? Because if you think of what happened during the Mariel boat lift -- and I don't know if he was writing Fidel's speeches or what he was doing. I don't want to say things I don't know anything about, okay? But to support what was going on when these people wanted to leave the Peruvian Embassy, and you saw in the movie -- that's real stuff when they're smacking those people over the head with pipes after they had come out of the Peruvian Embassy. Márquez is impressed with power. He's fascinated with Fidel Castro, and it has obscured his judgment. ![]()

Before Night Falls opens in theatres Friday, Feb. 9. See Film Listings for review.