Austin Struggles to Adjust as SB 4 Takes Its Toll on Immigrants

"We are not safer as a community when victims are running away from us rather than coming to us."

By Mary Tuma, Fri., April 5, 2019

After his mother and father passed away when he was young, Alberto Contreras Ramos' older brother took him under his care. But when his brother was murdered after an altercation with the local government, Ramos was alone and scared. Amid violence, he fled Guatemala for a better life in the U.S., landing in Austin a few years ago. The 20-year-old works in home remodeling construction, one of the estimated 400,000 undocumented immigrants statewide who make up half of the Texas construction workforce, according to a UT/Workers Defense Project report.

Last year, while Ramos was working a construction job in Round Rock, neighbors called the police because they found the music he and his co-workers were playing too loud. When officers showed up, they didn't seem too concerned, said Ramos, and eventually left. However, 30 minutes later U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers arrived on the scene and rounded up Ramos and two of his co-workers. Ramos, who has never been charged with a crime, was detained in the South Texas Detention Facility in Pearsall for more than four months. Living with his aunt, uncle, their daughter, and their 3-year-old special-needs twins, Ramos was providing vital financial support to the household, allowing his aunt to care for his cousins full time; when Ramos was detained, the family struggled to make ends meet.

"I felt like a criminal, I felt like I had done something wrong," said Ramos, as translated from Spanish. "The uncertainty of not knowing how long I was going to be [in detention] made me sad and stressed." An effort led by the Workers Defense Project and the Detained Migrant Solidarity Fianza Fund raised funds to post the unusually high $11,000 bond that allowed Ramos to go free. Today, he is working with an attorney to prevent deportation.

"People in my community are so nervous," he says. "They don't even want to call the police because they're so afraid they will get turned over to immigration."

Ramos' story highlights the likely effect of Senate Bill 4, or at least the heightened pattern of cooperation between ICE and law enforcement that SB 4 encourages. Following the 2017 passage of the legislation targeting "sanctuary cities" – a marquee issue for state and national Republican leaders – the undocumented community in Austin has faced unprecedented anxiety and fear. The law allows police to inquire about the citizenship status of anyone they stop or detain, and forces local law enforcement agencies to cooperate with federal immigration authorities regardless of the policies in their own jurisdictions. Local leaders, including police chiefs and elected officials, who are deemed to have flouted SB 4's provisions could face class A misdemeanor charges, possible jail time, and hefty civil penalties.

Following a legal challenge mounted by Texas cities including Austin, the conservative 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld most portions of the law last March, allowing SB 4 to take full effect just over a year ago. Currently, plaintiffs are determining next legal steps. Meanwhile, our city is grappling with how to comply with anti-immigrant state policies in its law enforcement operations and everyday life – policies causing disruption and fear that are taking a toll on immigrant communities.

"SB 4 Has Tied Our Hands"

When they were pushing SB 4 as part of their aggressive culture-war posturing in 2017, Republican lawmakers targeted newly elected Travis County Sheriff Sally Hernandez, who in office fulfilled her campaign pledge to limit the county's cooperation with ICE detainers – federal requests for local jails to hold inmates suspected of being undocumented immigrants for possible deportation.

Under Hernandez, the Travis County Sheriff's Office honored ICE detainer requests for those charged with or convicted of capital murder, murder, aggravated sexual assault, or human trafficking, but used its own discretion to honor other detainer requests on a "case-by-case basis." Now, compliance with those requests has become largely mandatory. In a recent interview with the Chronicle, Hernandez describes the transition as "difficult," saying the state policy has compromised law enforcement's ability to use its own judgment and strained its relationship with the immigrant community.

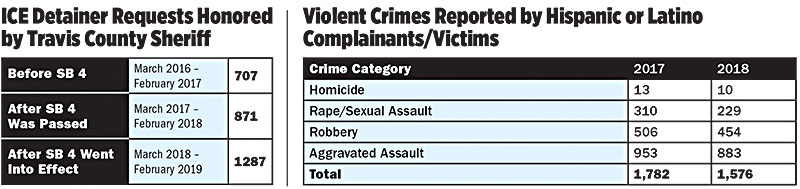

"Senate Bill 4 has tied our hands," says Hernandez. "It has made it much harder to build community trust. The fear among immigrants in the county is real." With SB 4 in place, the number of ICE detainers honored by Travis County has swelled, from 707 during the year before SB 4 was passed (March 2016–Feb. 2017) to 1,287 in the year since it took effect upon being upheld by the 5th Circuit (March 2018–Feb. 2019) – an 82% increase, according to data obtained by the Chronicle via open records requests.

Hernandez worries that victims of crime are not coming forward as a result of the law, pointing to four homicides that remain unsolved. "We know there are people out there with information that are not talking to us. It has an impact on us all," she says. The community's growing fear of federal authorities – and now, by extension, of local authorities – is also evidenced by the dwindling number of U visa applications, a protection meant to help undocumented immigrants who are victims of crime or have suffered abuse and who are willing to assist law enforcement in investigating criminal activity. In 2017, 83 U visa applications were filed; by 2018, that number came down to 25; this year, there have only been three applications filed, says Hernandez.

Anecdotally, some groups serving Hispanic and Latino clients have reported a chilling effect of rising anti-immigrant sentiment state- and nationwide – the same tide that carried SB 4 into law. For instance, the SAFE Alliance, which provides shelter, services, and resources to survivors of sexual assault and domestic abuse, says that while the overall number of contacts to its hotline has increased, it's seen a decline in Spanish-speaking callers over the past two years, according to staff reports relayed by spokesperson Emma Rogers. (The nonprofit stresses it does not ask callers or clients about immigration status, nor require any of its staff or partners to report evidence of undocumented status to law enforcement.)

Clients have told counselors at SAFE that their immigration status has been used as a "manipulation tactic or threat" by the persons who abused them; "several" clients have said they don't want to report abuse out of fear, sometimes because of what has happened to others who do. There is a general "increase in fear, distrust, and hopelessness" among clients who identify as Spanish-speaking immigrants, and some don't feel comfortable even leaving their house or driving, say SAFE staff.

Though it's difficult to draw firm conclusions, Austin Police Department data suggests there were fewer crimes reported by or against Latinos in the community following SB 4. Specifically, the number of incidents with at least one Hispanic or Latino complainant or victim dipped year over year from 2017 to 2018, according to data obtained by the Chronicle through open records requests. In 2017, homicide, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault reports peaked at 1,782 in total; in 2018, that total fell about 12%, with declines in each of those crime categories. "We are not safer as a community when victims are running away from us rather than coming to us," says Hernandez. "We want victims to know we are not interested in their status – we are interested in their safety."

More Questions Than Answers

Upon the 5th Circuit's ruling upholding SB 4, local immigrant rights and criminal justice advocates pushed for a "Freedom Cities" policy in an effort to increase transparency and accountability. In June 2018, the Austin City Council passed a resolution that, among other things, requires police officers who ask about immigration status to also inform people of their right to not answer. The resolution also requires quarterly reports to Council regarding information sharing and requests for cooperation between the Austin Police Department and ICE or other federal immigration officials, along with data on any city resources used to further federal enforcement.

On March 1, Police Chief Brian Manley presented his first of these reports to City Council, providing a peek into what appears to be robust cooperation between ICE and APD. It showed that between January and December 2018, APD assisted or cooperated with ICE nearly 600 times, including providing utility reports (189 records); images from license plate readers (26); booking photos (63); police reports (194); and vehicle registrations, insurance reports, phone subscriptions, driver's license reports, and school district reports. The department identified six officers, a total of 72 work hours, and some $4,000 in resources devoted to assisting ICE.

This detailed information troubled advocacy group leaders, who pointed to the report as evidence of why Austin needed a Freedom Cities policy in the first place. For many, the data raises more questions than it answers. "The data begs some very serious and fundamental questions, including [under] what circumstances this information was sent to ICE," says Jose Garza of the Workers Defense Project, pointing to instances in which information possibly flowed from Austin ISD or Austin Energy to ICE. "Without knowing more, we don't have a transparent picture."

In response to the Chronicle's questions regarding how much of APD's cooperation with ICE was mandatory and how much was discretionary, department spokesperson Anna Sabana referred to SB 4's significant restrictions. "[The] law prohibits law enforcement agencies and cities from forbidding or materially limiting their police officers from assisting or cooperating with federal immigration officers as reasonable or necessary," she wrote in an email. "Accordingly, APD cannot adopt any policies or regulations that would prohibit or materially limit its police officers from sharing information with ICE when it is reasonable or necessary to do so, or it could face substantial penalties, including fines of up to $25,500 per day."

When asked how APD obtained school district and utility report information to share with ICE, Sabana wrote that the department has access to information that is "important to conduct criminal investigations" through its relationships with other agencies and through access to law enforcement databases. "When federal immigration officers seek assistance or information from APD, SB 4 compels us to provide that assistance or information."

City Council Member Greg Casar, who championed the Freedom Cities policy, called for greater transparency and pointed out the dangers of emboldening those who may be prone to anti-immigrant sentiment. "These instances of ICE collaboration may have been forced by SB 4, [or] some of them may reflect a misuse of the city's power to support deportations," he said.

Filings in federal district court, obtained by the Chronicle, show a relationship between ICE and APD that appears cozier than that which SB 4 "compels." According to these documents, at least six APD officers allegedly helped ICE investigate, track, and target an undocumented immigrant for deportation. A 27-page motion filed in February requests that U.S. District Judge Lee Yeakel's court suppress information obtained as a result of an illegal warrant. It claims an ICE officer, relying on APD interactions that ICE helped orchestrate, issued a false and unlawful arrest warrant that failed to establish probable cause. The ICE officer "knowingly misrepresented material facts" in order to obtain the warrant, and as a result violated First and Fourteenth Amendment rights.

ICE officers investigated Luis Guevara-Gonzalez, even using his Facebook posts and photos, and enlisted the assistance of APD, who, after being given his street address, assured ICE officers that they would "be actively looking for Guevara." Following ICE's request for help, APD officers "coincidentally" entered the home address ICE had provided them. "Another officer went to this house tonight on a completely unrelated call (mental health call and it was a wrong address)," an officer wrote to ICE. "If we are able to get an arrest on him should we contact you or will Travis County notify [ICE] automatically?" Working with APD "paid off," an ICE officer wrote to his colleagues afterward.

A couple of months later, APD was dispatched to the same address after a 911 call reported gunshots; Guevara, a victim, had been shot while seeking to protect his brother from a gunman. Guevara and his pregnant girlfriend, who went into a seizure, were taken to Dell Seton Medical Center for treatment, where an APD officer collected a report from Guevara. Two weeks after the shooting, an "Officer Valentin" with ICE submitted a criminal complaint to U.S. Magistrate Judge Mark Lane, seeking an arrest warrant against Guevara – who at this point had never interacted directly with ICE, and the agent had neither verified Guevara's presence nor confirmed his identity. In other words, immigration authorities did not have and should not have had actual knowledge that Guevara was physically present in the U.S., making his warrant misleading and unlawful, according to the court documents.

That's why, the motion claims, ICE's Valentin had attempted to "orchestrate" an "encounter" between APD officers and the address ICE provided them, and then conduct a "post hoc verification of identity through multiple layers of APD officers." Guevara was "lulled into believing APD officers were assisting him as a crime victim; in actuality, APD contact with Mr. Guevara constituted investigation on behalf of ICE." In an attempt to locate Guevara, ICE reached out to APD; pulled AISD school records for Guevara's daughters, who are U.S. citizens; and sought to get his girlfriend's hospital records from Dell Seton to see what info she "gave up" after she was admitted for her seizure.

APD arrested Guevara on his front lawn, on the federal warrant obtained by Valentin, on July 7, 2018. It remains unclear why Guevara was targeted by ICE in the first place. He and his attorneys plan to be in court to fight the warrant this May.

"This is a clear case of how laws like SB 4 can damage people's lives," says Casar, adding that the law doesn't require police departments to "go out of their way" or use abundant resources to assist ICE. "It shows exactly why people in the immigrant community are afraid of police interaction. Anything from a broken taillight, or just being in your home as in Luis' case, can lead to arrest and deportation." Casar says he has approached Chief Manley about the case and is seeking answers regarding whether the cooperation was compelled by SB 4 or discretionary.

The Right of Sanctuary

The term "sanctuary" itself refers to a "holy place," the worship space of a church; the freedom from arrest granted under English common law to those taking refuge in churches gave rise to the legal concept that SB 4 seeks to invalidate. Alirio Gámez, who fled violence and threats to his life in El Salvador, along with Hilda Ramirez and her 12-year-old son Ivan, has taken refuge in two Austin churches, St. Andrew's Presbyterian and First Unitarian Universalist, for more than a year. The undocumented asylum seekers and leaders of the Austin Sanctuary Network were notified in mid-March that their respective requests for deferred-action extensions on their deportations were denied, without an explanation. They were scheduled for a check-in with ICE on March 19, the day after their current temporary stay of deportation expired.

Ramirez and Gámez feared they would be taken to detention and deported if they met with ICE, due to the growing pattern of retaliation. Immigration advocacy group Grassroots Leadership points to the examples of Samuel Oliver-Bruno, a North Carolina church sanctuary leader who was detained and deported after appearing for his ICE check-in in November, and Claudio Rojas – featured in the Sundance award-winning film about Dreamers, The Infiltrators – who was detained by ICE in February during what was supposed to be a routine check-in.

Claudia Muñoz, immigration programs director at Grassroots Leadership, notices the uptick in pushback against migrants who advocate for their rights. "It seems like ICE field officers are now more emboldened than ever to do what they want, thanks to SB 4 and the anti-immigrant tone overall that has changed the culture," says Muñoz, "even in a progressive city like Austin."

U.S. Reps. Joaquin Castro and Lloyd Doggett contacted ICE Field Director Daniel Bible to request reconsideration of Gámez and Ramirez's deferred action; however, Bible declined. Warrants for their arrest will be issued and their cases have been referred to fugitive operations in Austin, Muñoz was told. The three Austin residents have returned to sanctuary and will continue to remain there for the "foreseeable future."

"If thousands of community members and elected officials determine that we are welcome in this community, why is ICE not listening to them and terrorizing us?" asks Ramirez. "They know we are not a priority for deportation and granted us discretion, and then, without reason, they took it away. ICE doesn't think they have to listen to anybody, and that's dangerous. I am going to continue fighting because I have a community behind me and because my faith is bigger than any terror they can inflict on me."

Immigration attorney Kate Lincoln-Goldfinch says she's seen a rise in non-criminal arrests leading straight to deportation proceedings. (Simply being present in the U.S. without documentation is not a crime, but a civil violation.) In the past, a mother of U.S. children with no criminal record, for instance, would get to bond out immediately and not face proceedings; but within the past year, Lincoln-Goldfinch is witnessing nearly every person apprehended transferred to ICE custody, detained, and sent to immigration court. "There seems to be no exercise of prosecutorial discretion – every person is in the purview of being detained and deported," she says. Nationally, ICE has set a new record for arresting undocumented people with no criminal history: In December, 63.5% of undocumented people arrested by ICE had a criminal record, the lowest number since the federal agency began keeping compiling the data in 2012. That means more than one-third of those arrested by ICE are people who have committed no crime, despite the president's campaign trail vow to go after "violent" criminals gaining unlawful entry.

Legislators Try to Push Back

On March 14, more than 100 immigrant rights advocates converged on the Capitol's south steps to urge for the repeal of SB 4 and the protection of the nearly 20-year-old Texas DREAM Act (which helps undocumented Texas residents attend college), and also to ensure no state funding flows to Trump's proposed border wall. "SB 4 has got to go!" the crowd chanted following encouraging speeches from lawmakers including Rep. Armando Martinez, D-Weslaco, and Rep. Ramon Romero, D-Ft. Worth, and passionate stories from undocumented immigrants who expressed the constant fear they and their families experience daily. The rally followed a similar gathering in early March where 100 advocates outlined their legislative agenda, which includes a full repeal of SB 4, outside the Capitol.

These advocates are getting behind SB 672 by Sen. José Menéndez, D-San Antonio, which would prevent police from racial profiling or enforcing federal immigration law, and its companion House Bill 2266 by Rep. Rafael Anchía, D-Dallas. (Both bills have been referred to the State Affairs Committee in their respective chambers.) Anchía, chairman of the Mexican American Legislative Caucus, notes the damage SB 4 and the statewide anti-immigration fervor that spawned it have inflicted on communities throughout Texas. At the time of its passage, the legislation was declared an "emergency" by Gov. Greg Abbott, but in reality was a manufactured solution to a problem that didn't exist, Anchía told the Chronicle; across the nation, fewer than 1% of ICE detainers that were not honored by law enforcement agencies came from Texas, according to ICE's own data.

Part of the aim of Anchía's HB 2266 is to eliminate the "unprecedented power" that SB 4 grants to the Texas attorney general over local authorities. In November, A.G. Ken Paxton sued San Antonio Police Chief William McManus, his department, and City Manager Sheryl Sculley for purportedly failing to comply with SB 4, requesting $11 million in civil penalties. "I find it very ironic that the same people that support local control believe a politician in Austin is going to know better than their own police chiefs and sheriffs when it comes to how to keep their local communities safe," Anchía said.

More than halfway to its finish line, the current legislative session has seen a relative calm surrounding immigration – but the next two months, of course, could change that. Advocates are keeping eyes on HB 413 by Rep. Kyle Biedermann, R-Fredericksburg, which seeks to repeal in-state tuition for undocumented immigrants, part of the Texas DREAM Act that's been in place with bipartisan support since 2001. While the general tenor in the House has been respectful so far, Anchía points to efforts by top Texas Republican officials to suppress voting rights among the Latino community with the bungled "voter fraud" panic unleashed by Secretary of State David Whitley, along with the pro-border wall drumbeat taken up notably by Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, as reasons for the pro-immigrant side to constantly keep its "guard up."

Despite all the terror SB 4 and other attacks on immigrants have caused the community, Workers Defense Project's Garza stresses that the pressure has also led to a "stronger, more sophisticated and durable" organizing and mobilization structure among immigrant advocacy groups, who have been pushed to work together in a united front. "We should make no mistake, there are mothers and fathers living in fear as they drive their children to school. There are so many families living with mass anxiety wondering if their sibling or parent will come home from work safely," he says. "But at the same time, there is an enormous amount of hopefulness and resilience from the community – when we stand together, we have unlimited power."

SB 4’s Impact on Law Enforcement: By the Numbers

“Senate Bill 4 has tied our hands,” says Travis County Sheriff Sally Hernandez, forcing her office to hold more jail inmates – including nonviolent offenders and those not ultimately charged with crimes at all – for eventual deportation by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Meanwhile, the bill’s chilling effect on immigrant and Latino/a cooperation with law enforcement may explain a 12% year-over-year drop in reporting of serious crimes to Austin police.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.