Are Dogs Gentrifying East Austin?

Eric Tang’s latest addendum addresses displacement, and dogs, in Eastside tract

By Michael King, Fri., June 1, 2018

In March, UT Austin's Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis issued a report on the effects of Eastside gentrification on longtime residents who have remained in their homes while many of their previous neighbors have moved away. ("Those Who Stayed: The Impact of Gentrification on Longstanding Residents of East Austin," by Eric Tang, et al.) The report was based on interviews with longtime residents of a single central East Austin census block (63 heads of household among 341 homes, selecting residents who have lived in their homes since at least 1999). The authors found that "the drastic reduction in the number of children is perhaps the most profound and troubling marker of gentrification: the neighborhood we surveyed lost half of its child population between 2000 and 2010."

In starkly demographic terms: "Between 2000 and 2010, this neighborhood's Black population decreased by 66 percent, its Latino population decreased by 33 percent, and its white population increased by 442 percent."

The researchers asked longtime residents – "mostly older, retired Black and Latino residents who live in the same homes in which they were raised and in which they raised their own children" – why they've decided to stay when so many of their longtime neighbors have moved elsewhere. Most of those surveyed described the recent changes as either negative, or primarily for the benefit of (mostly higher-income, white) newcomers. Yet they say they have stayed for more intangible reasons. "Nevertheless," write the authors, "these longtime residents remain because they feel a deep sense of connection – a historical rootedness – to their communities. They affirm a responsibility to stay in East Austin and they do so despite gentrification, not because of it."

One curious detail in the survey responses was a perception that there are now more neighborhood dogs than children. The impression was repeated often enough that the researchers decided to document it. This week they released an "addendum" to the March report, addressing the question, "Are There More Dogs Than Children in East Austin?" The answer is yes, with a notable qualifier: "Longstanding residents are correct in their perceptions. Dogs now outnumber children in the neighborhood nearly two to one. A profound absence of children, not an abundance of dogs, explains the disparity. Dog ownership rates in the neighborhood appear to be on par with national averages. However, the 17-and-under population in the neighborhood falls well below the city and regional averages."

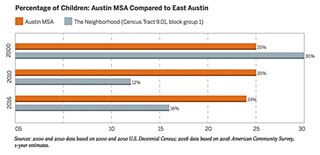

Researchers surveyed 171 households in the neighborhood, and counted 66 children and 116 dogs. "The absence of children leaves one with the impression that there is an abundance of dogs," the researchers write, "but our findings suggest that the former factor, not the latter one, tells the truer story about gentrification." From 2000 to 2016, according to census data, the percentage of children in the studied neighborhood dropped from 30% to 16%, in contrast to the broader Austin metropolitan statistical area (roughly constant at 24-25%).

The authors recommend "public intervention" – e.g., "the creation of new affordable housing (as well as the maintenance of existing affordable units)" as "the key factor that will allow for the repopulation of families with children in the neighborhoods of central East Austin."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.