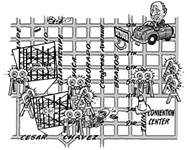

Event Street Closures: Compromise Ordinance Doesn't Solve Barricades

Stakeholders agree on a proposal for closing streets for special events

By Laurel Chesky, Fri., June 5, 2009

A new street closure ordinance, adopted by City Council on April 30, codifies a well-hammered compromise between organizers of outdoor special events and the people and neighborhoods they inconvenience. A task force of stakeholders worked for six months to rewrite the city's street closure ordinance, which regulates the process of obtaining a permit to close city streets. The task force consisted of a race promoter and representatives of nonprofits that stage fundraising events along with neighborhood associations, churches, and business owners.

About 150 festivals and road races take place in Austin each year, mostly in the city's central core. On any given weekend, streets and intersections somewhere in the city are barricaded and drivers rerouted, frustrating residents, churchgoers, and business owners. The draft rules are scheduled to be presented to the Urban Transportation Commission on June 9 and then posted for public comment for 30 days.

The new ordinance and rules would:

• Lengthen the permitting processing period for special events from 60 days to 180 days, giving event organizers and city staff more time to plan.

• Require written notification to all residents living within a half-mile of the event or race course 90 days prior to an event.

• Disallow the closing of Fifth and Sixth streets and Lamar Boulevard in Central Austin and the closing of the Congress Avenue and First Street bridges simultaneously.

• Allow the denial of a street closure permit if 20% of affected residents or a single neighborhood association objects.

"The result is a hybrid ordinance that wasn't a home run for anybody; everyone one on all sides of the issues had to compromise, and that's a good thing," says John Conley, Austin Marathon executive director and a task force member. "Certainly it makes the race production business more challenging, but it's really too early to know what the true impact is."

Conley and other event organizers are more worried about what the ordinance does not do: address the issue of street barricading. Barricade costs have skyrocketed over the past few years, putting many small fundraising events for nonprofits out of business. And the new rules may increase barricading costs because they require traffic-control devices to be set down later and picked up earlier, potentially adding labor costs.

Event organizers must submit a traffic-control plan to the city's Right-of-Way Management office. The plan proposes determining how many traffic-control devices – orange cones, street barricades, and road signs – are needed to block off intersections, warn drivers of closures, mark detours, and delineate the race course. Race directors report that city staff often double the required cones, barricades, and signs – and expense – for the plans. Race organizations pay a rental company to put down and pick up the devices, and it's not cheap. Despite spotless safety records, two of the city's most prominent races have seen their barricading costs soar. The Austin Marathon's traffic-control costs jumped from $40,000 in 2005 to $80,000 in 2007. In 1995, the 3M Half Marathon & Relay paid $126 for barricading. This year it paid $40,000.

A large corporation can still afford to donate money to charity – this year 3M wrote a $30,000 check to Any Baby Can in association with the race. But lacking a major sponsor, the Austin Marathon – which brings in an estimated $15 million to the local economy, Conley says – no longer directly benefits charity, although it does enable individual participants to raise money for nonprofits. And for nonprofit organizations, race costs cut directly into their fundraising. Barricading costs have forced the Susan G. Komen Race for the Cure, a 5K road race that raises money for breast cancer research, to move this year from Downtown to the Domain. "Unfortunately when races have to raise costs by $1,000, $2,000, $3,000, that really impacts the nonprofits and the clients they serve," says Michelle Graham of Bounce Marketing & Events, which stages the Thundercloud Subs Turkey Trot benefiting Caritas.

Jason Redfern, Right-of-Way Management division manager, says tighter cone spacing and additional barricades are necessary to keep event participants safe, as growing traffic and increased population density within the city call for heightened traffic safety measures. A city ordinance passed in December 2007 tried to help small events with barricading costs. It mandated the hiring of 13 city employees to design traffic plans and to set up city-owned traffic cones and barricades, eliminating the need to hire private traffic engineers and rental companies. But the plan was never fully funded, and the city-run barricading service didn't come to fruition.

Redfern says the city is working with barricade companies to seek out lighter, less labor-intensive barricading equipment. His department is also working with the Austin Police Department to possibly increase the use of officers during events. Having police officers directing traffic reduces the need for barricading, and, although events must pay the officers, it's generally a more cost-effective way to control traffic. It's also better for drivers, because officers can allow traffic to flow during lulls in the race.

"We're working on it, trust me," Redfern says. "We want these events to happen in Austin. They're good for the city."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.