Developing Stories: What's Wrong With the Super PUD

The proposed PUD amendments won't fix the problems without a plan

By Katherine Gregor, Fri., June 6, 2008

That's the core issue at stake in a well-intentioned, long-belabored, but incomplete new planned unit development zoning ordinance heading to City Council June 17. After enduring long, grisly 2006-2007 neighborhood-developer battles over PUDs – the East Avenue/Concordia PUD, the Fairfield/Hyatt PUD, the St. David's PUD – Council Members Mike Martinez, Brewster McCracken, and Lee Leffingwell took action to fix the inadequacies exposed in the PUD ordinance. Martinez said recently that the members had seen the need to put neighborhoods on more equal footing with developers and to shape large projects to reflect community values.

What they haven't yet seen is the need to explicitly require stronger urban design plans for these massive (10 acres and more) mixed-use projects. That's the essential "Super PUD" amendment missing from the draft currently slated for a public hearing and likely first-reading vote.

The proposed Super-PUD amendments (which apply to both planned unit developments and planned development agreements) address these special zoning categories. They would require or encourage mixed-use PUDs to incorporate the city's Commercial Design Standards, affordable housing, locally owned businesses, public art, enhanced green building, and more. The public benefit of having PUD zoning at all is to provide the design flexibility needed to produce "superior" projects by allowing a project plan that treats the site as one holistic unit. Toward this end, PUD and PDA zoning free a developer from adhering to the city's lot-by-lot zoning requirements and protections: height restrictions, impervious cover restrictions, and so forth.

Therein lies the problem. To developers angling to get more entitlements on their land, P-U-D offers an alternate spelling of L-O-O-P-H-O-L-E. A request for PUD rezoning typically has resulted in an owner/developer gaining significant entitlements to build bigger and taller – while doing very little to truly create a superior project. Inappropriately, the zoning is sought even on small sites. After the East Avenue/Concordia debacle, Brewster McCracken memorably called PUDs "the path of least resistance for doing the wrong thing."

"St. David's PUD is an example of a very bad PUD," noted Bart Whatley, an architect and stakeholder group participant. He said the hospital gained entitlements to double the project's density "largely on an integrated pest-management plan and a low level of green building for any new structure. A PUD that allowed the hospital not to have to bother with certain city codes and surrounding citizens was granted largely because of St. David's political pull."

It's the planning, stupid

The tools that could actually solve the underlying problems with PUDs reside in the urban design and planning tool kit. Like other heavy equipment – surgical saws, appellate lawsuits, construction cranes – they require the guiding hands of trained professionals. But the proposed amendments (resulting from a yearlong, council-led stakeholder process) don't require an urban design plan. Instead, they're focused on two changes: 1) giving elected officials an early voice when PUD zoning is first requested and 2) defining required Tier I features (baseline requirements) needed to qualify as "superior," plus optional Tier II "density bonus" features, needed to earn increased entitlements.

Missing is the structure that organizes the parts. "Isn't urban design a community value?" asks Jana McCann, an urban planner with ROMA Austin.

A "superior" PUD project results from superior planning. The insufficient site plan detail required by the city from a PUD developer is the great weakness in Austin's current PUD ordinance – yet it's unaddressed in the amended version. Since the fight over the East Avenue PUD – the redevelopment of the Central Austin Concordia University campus – lit the fire to the whole PUD amendment process, it's worth refreshing our civic memory of how that unhappy dispute was finally resolved (see "Developing Stories: Concord – At Last," March 30, 2007). Not with affordable housing units. Not by a standard facilitator. Not by council members. By good urban design. Resolution emerged only when ROMA crafted a responsive, detailed, and clear master "framework plan" for the 22-acre infill project.

Why then don't the ordinance amendments reflect this lesson learned, by requiring a master plan? Because developer and real estate interests fought it. Neither they nor city staff leading the effort seem to understand how a master plan protects all interests, public and private. So council members and staff settled for a political/policy solution, rather than an urban design tool. One might eventually drive a nail into a two-by-four by banging at it with a screwdriver. But why overlook the hammer lying next to it?

Density Bonuses

Starting with the idea that an idiot-proof matrix or point system could solve land-use planning problems was the fatal flaw. Council and staff approached PUDs as a "density bonus" problem: How to trade increased entitlements (such as height) for features that embody community values (such as parks and low-income housing). Insisting the developers "give back" is good policy, and a checklist or point matrix can work for a Downtown high-rise condo tower. But it misses the mark for a complex, large-scale urban infill development.

"The PUD ordinance as currently drafted is more of a prescriptive density-bonus program, based on existing zoning, than a flexible design tool," noted Richard Weiss, an architect in the stakeholder group and a Design commissioner. "Defining uniform criteria for 'superiority' is extremely difficult when every site and project is different, given that the basis of PUD zoning is to allow for flexibility both in design and execution."

These problems aren't solved by inserting an early review by council members – who have no formal urban design training. Now that we're a big city, Austin badly needs a high-level, empowered city architect or city planner to advise council and other staff. It also needs to use its staff planners – and add certified urban design professionals – to advise the city on such matters.

Kill The Gatekeepers

Stakeholder group participants praise the community-benefit requirements as a big step in the right direction. But some remain unhappy with the specifics – particularly for affordable housing. A recent Community Development Commission resolution called for PUD affordability levels in the amended ordinance to be lowered to a citywide standard of 60% (rather than 80%) of median family income for rentals and 80% MFI for ownership. Commissioners also recommended raising the low $6-per-square-foot fee allowable in lieu of on-site units.

Also dissatisfied is the Real Estate Council of Austin. Unsurprisingly, its developer-heavy membership (represented on the stakeholder group by Jeff Howard) wants to preserve the freewheeling latitude enjoyed to date. "RECA has consistently maintained that the PUD zoning district rules did not need to be amended," states a May 29 letter to council from RECA President Tom Terkel.

Citing good examples (such as the Lakeline Station PUD), RECA basically says "trust us." But that project sailed through smoothly because it had a top-tier urban designer, Peter Calthorpe. The letter alleges "serious legal, procedural and practical problems" with a gatekeeping council subcommittee and with required affordable housing. Although acting out of self-interest, RECA may be right in urging council not to pass the amendments as drafted. Certainly a subjective council review works against predictability for developers. But RECA could best protect members' interests by supporting a PUD master plan requirement – the tool to produce better, more marketable projects while preventing expensive mistakes, battles, and delays. Certainly it makes more sense for council members (supported by urban design staff) to review a cohesive, project-specific master plan than to impose a one-size-fits-all checklist.

Stakeholder Cory Walton, active in the Bouldin Creek neighborhood, also objected to the council subcommittee – but for reasons opposite to RECA's. While lauding the community benefits specified, he said, "In effect, these 15 pages of lofty language and matrixes for compliance to superior standards are meaningless, because the council can still play Let's Make a Deal with the developer behind closed doors to waive any part of these standards."

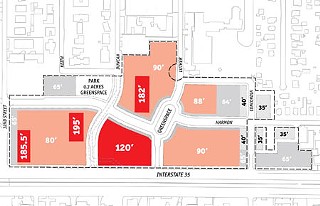

In the East Avenue PUD, Austin has a great model for a framework plan. Its essential elements: streets and other infrastructure, pedestrian-oriented uses, open space, sites for each parcel and building type, a circulation/transit plan. The city can prevent fights by requiring PUD/PDA developers to show precisely how their big, dense new project will be sensitively integrated into the surrounding neighborhoods and urban fabric, including roadways and transit.

It wouldn't take much to fix the PUD amendments. To require adequate master planning, noted McCann: "All it would take is one more paragraph that says, 'Let there be design.' Require developers to integrate all of these various menus of community values into an overall urban design framework plan." As she noted, "It's the master plan or framework plan that synthesizes all of those community values into a physical form."

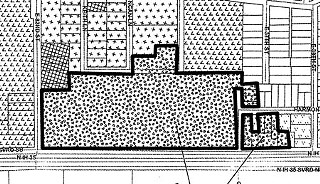

Bad Plan, Good Plan: East Avenue PUD

Top: A mysterious "black box" site plan was all the city's PUD ordinance required (and still does). Its inscrutability contributed to a long neighborhood-developer battle royal.

Bottom: A council-ordered urban design "framework plan" worked out the missing details. Its thoughtful features won neighborhood approval for the development.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.