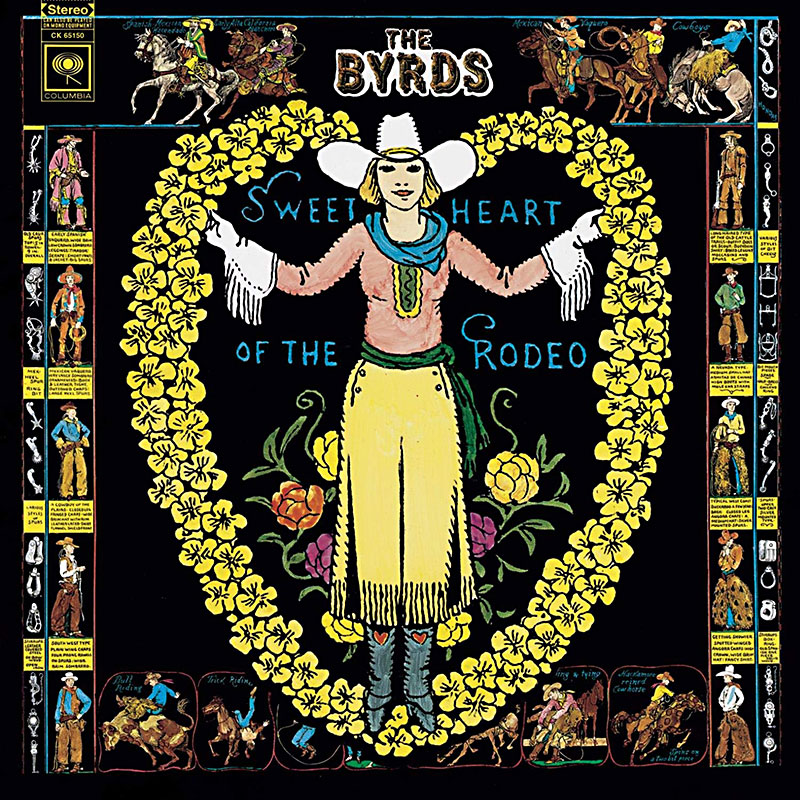

The Byrds' Sweetheart of the Rodeo Turns 50

The landmark album spins at the Moody Theater via two of its makers and their virtuosic friends

By Tim Stegall, Fri., Nov. 9, 2018

"The Byrds were ahead of the curve, and they taught many how to play country music."

So says Marty Stuart, the 60-year-old Mississippi hillbilly rocker with a rhinestone cowboy wardrobe and a Ziggy Stardust mullet, warming up to some favorite subjects: folk rock, its psychedelic architects, and country-rock-pioneering 1968 album Sweetheart of the Rodeo. Stuart and his expert band the Fabulous Superlatives have joined original Byrds Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman in playing Sweetheart and related material live to celebrate the LP's 50th anniversary. Stuart's excited for November 10, the day the tour pulls up to ACL Live at the Moody Theater.

"I think it's pretty cool we're bringing it to Austin," he enthuses. "I distinctly remember back in January, we were in Austin for the day, and Roger reached out from an airport in Buenos Aires. He said, 'I have an idea!' I said, 'Anything you wanna do, let's go! This sounds wonderful.'"

As do McGuinn and Stuart when performing together.

Forged during the filming of an unreleased Dolly Parton IMAX film in 2010, the musical alchemy is obvious to all in a popular YouTube clip of the pair essaying Sweetheart's signature honky-tonking of Bob Dylan's "You Ain't Goin' Nowhere" on a corner of the set for the cell phone of Roger's wife Camilla. Then there's the fact that Stuart possesses a 1954 Fender Telecaster owned by fiery Byrds string-bender Clarence White, purchased in 1980 from his widow. White's pedal steel mimicry drenches Sweetheart, facilitated by a Tele B-Bender, a device he and later Byrds drummer Gene Parsons invented that mechanically raises the pitch of the guitar's B-string.

"That guitar has Clarence's voice inside it," claims its guardian of nearly four decades.

Every bit the one-in-a-million virtuoso as Clarence Joseph LeBlanc (1944-1973), Stuart channels his precursor's voice nightly, honoring an album he loves dearly. Had its group leader executed his original vision for the album – a history of music, all of it – that might not be the case today. McGuinn, 76, recalls his scheme.

"A two-record set of early music from Europe," he begins. "Then the Renaissance and baroque, then the Celtic music that got imported into the Appalachians and became country and folk music. Then, ultimately, rockabilly and rock & roll, followed by jazz and ending with synthesizers and space music. It was a very ambitious project.

"And nobody wanted to do it."

At that juncture, the Byrds were just McGuinn and Hillman, singer/guitarist David Crosby and drummer Michael Clarke having exited during the band's fifth LP, 1968's The Notorious Byrd Brothers. Facing a college tour that same year, Hillman drafted drumming cousin Kevin Kelley into a threepiece Byrds. Their sparse live sound prompted the hire of a pianist by McGuinn (see "Roger's Right Hand," June 27, 1997).

Enter Gram Parsons, scion of a wealthy Southern family who'd been through the same folk scene that spawned the Byrds, beside his own rock & roll outfit, the International Submarine Band.

"Our conversation was mostly about country music, how he wanted to bring it to the youth," says Austinite Earl Poole Ball, the 77-year-old ace country pianist who worked on the ISB's 1968 long-player Safe at Home and later on Sweetheart, which Parsons stealthily made over in his image by picking up a guitar one day at rehearsal and playing George Jones and Merle Haggard tunes.

"We'd hired a pianist," McGuinn laughs now, "but we got George Jones in a rhinestone suit!"

Parsons suggested cutting a country record in Nashville, an idea in line with McGuinn's folk roots and Hillman's bluegrass background. As the latter muses today at 73, "A country record was not a stretch at all." 1965's Turn! Turn! Turn! first flashed twangy via Porter Wagoner's "A Satisfied Mind." McGuinn drawled "Mr. Spaceman" on 1966's Fifth Dimension, while '67's Younger Than Yesterday featured Hillman's countryish "Time Between" and "The Girl With No Name," plus Clarence White's Telecaster brilliance. Byrd Brothers' "Goin' Back" and "Wasn't Born to Follow" were saturated in pedal steel.

"It's different from Bon Jovi making a country record," snorts Hillman. "They don't have that background. They do what they do really well, but a lot of rock bands say, 'Let's go to Nashville.'

"It wasn't the same with us. We had something to draw on."

The Byrds occupied Columbia Records' Nashville studio March 9-15, 1968. Joined by producer Gary Usher, they were supplemented by top Music City sessioneers, including steel guitarist Lloyd Green and fiddler/banjoist/guitarist John Hartford, whose "Gentle on My Mind" had broken Glen Campbell to the masses. Recording followed in the label's Hollywood facility, April 4-May 27, with Ball and another steel whisperer in JayDee Maness, alongside White and Electric Flag keyboardist Barry Goldberg.

The material spanned the Louvin Brothers' "The Christian Life" and Merle Haggard's "Life in Prison," Stax/Volt singer William Bell's "You Don't Miss Your Water," and Woody Guthrie's "Pretty Boy Floyd." Parsons contributed two superb originals, "One Hundred Years From Now" and his future signature tune, "Hickory Wind." Being Dylan's finest interpreters since initial jingle-janglin' 1965 hit "Mr. Tambourine Man," the band continued the tradition with set-opening and -closing extracts from The Basement Tapes: "You Ain't Goin' Nowhere" and "Nothing Was Delivered."

"Lloyd Green said it was the highlight of his musical life," says McGuinn. "He was used to a very structured system of recording in Nashville, where they say, 'Okay, on bar 32, you're gonna play a little lick for two bars, then you go quiet.' We came in and said, 'Hey, man, just play any way you feel like!'"

Ball says the L.A. sessions weren't dissimilar. Then a West Coast studio pro, he'd grown used to the ivory trade on Haggard and Buck Owens sessions at the Capitol Tower.

"Ken Nelson, who produced there, wanted you to get three songs in a three-hour session," recalls the longtime local (revisit "A Honky-Tonk Song," Dec. 24, 1999). "Everybody had to show up on time, be presentable and sober, and get it done! Buck Owens & the Buckaroos would show up on time and dressed in nice sport clothes. They'd be rehearsed, and they'd played a lot of the material on their shows. They knew the tunes, and the ones they didn't were a quick study.

"That's how you had to be.

"With the Byrds, I'd get there on time, and so would JayDee Maness. These people came in when they felt like it. I had to get used to how rock acts had contracts allowing them to take their own developmental creative time. The Byrds would show up eventually, maybe a little stoned. I was afraid to even drink a beer while recording! I wasn't smoking weed at that time.

"I had to adjust, relax, and go with the flow."

The Byrds' long-haired/dope-smokin'/countercultural ways clashed with Nashville's more buttoned-down style, when even Willie Nelson hid his stash and kept regular barber appointments.

"In 1968, we had the Vietnam War and hippies, and people who didn't burn their draft cards down on Main Street," jokes McGuinn, quoting Haggard's "Okie From Muskogee." A Grand Ole Opry appearance arranged by Columbia, for which the band cut their hair, underlined the divide. Audience members heckled them as they played.

"In hindsight, we were very rude and disrespectful," admits Hillman. "They wanted us to do 'Sing Me Back Home,' which Merle Haggard had a huge hit with at the time. I remember Tompall Glaser coming up and saying, 'Fellas, ya gonna do "Sing Me Back Home" for us right now?' And Gram jumps up and says, 'No, we're gonna do "Hickory Wind!"'

"We thought it was hip at the time."

This ensured an instant ban from the Opry, and an appearance on country radio institution Ralph Emery's program didn't go much better. The famed DJ mocked them on-air.

"We went with our single, 'You Ain't Goin' Nowhere,'" McGuinn recalls. "Ralph didn't want to play it. He asked me what it was about. I said, 'I don't know, it's a Bob Dylan song!'"

The incident inspired McGuinn and Parsons to write "Drug Store Truck Drivin' Man," eventually recorded for Dr. Byrds & Mr. Hyde. Other worries plagued post-production. For starters, Parsons proved problematic.

Singer and indie label owner Lee Hazlewood waved an International Submarine Band contract around, so McGuinn had to recut three of their pianist's vocals to ameliorate the pop auteur, for which Parsons held a grudge until his 1973 death. Some reports hold that the latter also wanted top billing over the established hit act. He left the Byrds in London before a South African tour, claiming problems with apartheid. Hillman thinks he really wanted to hang out with the Rolling Stones.

"Roger and I introduced Gram to Mick and Keith," says Hillman. "That was a big mistake. He immediately gravitated to that. One time, during the Flying Burrito Brothers, I had to track Gram down. We had a gig, and he was at a Stones session in L.A. Mick stops the session, goes up to Gram, and says, 'Chris is here. You've got a gig tonight.' Gram's saying, 'Nah, I wanna ... ' and Mick says, 'You're not hanging out with us. We're working. You have a responsibility to your fans.'

"Gram had the talent. He was a bright guy. He was funny. We wrote great songs together in the Burritos. Sweetheart wouldn't have happened without him. I've forgiven him a lot.

"But Dwight Yoakam told me six months ago, 'Y'know, you can't be a country singer with a trust fund.' That's Gram in a nutshell. He was getting $50,000-60,000 per year. He was seduced by the trappings of rock stardom, but he wouldn't put the work in. He didn't have to. He could hire the limos on his own.

"I loved the man, but he had problems."

Most legends are problematic. Only Parsons' vocals on "Hickory Wind," "You're Still on My Mind," and "Life in Prison" made the finished record. White replaced him after the South African tour, and Kevin Kelley was dismissed. The duo were Byrds five months.

Sweetheart spent 10 weeks on the Billboard charts, peaking at No. 77. "Nowhere" reached No. 74 on the singles charts, while follow-up "I Am a Pilgrim" didn't chart. Contemporary reviews dismissed it. This didn't stop the threads binding the Byrds' country rock masterpiece from unraveling and weaving through the greater culture.

Two months later, the Beau Brummels issued their own Nashville disc, Bradley's Barn. Hillman followed Parsons out of the Byrds into the Flying Burrito Brothers, offering their own Sweetheart amplification in February 1969, The Gilded Palace of Sin. Then came Dylan (Nashville Skyline), Parsons' beloved Rolling Stones ("Honky Tonk Women"), and Byrds super spin-off Crosby Stills Nash & Young ("Teach Your Children").

Linda Ronstadt, Poco, and the Eagles all took a page from the Sweetheart playbook. As did Austin's cosmic cowboy wave and anyone calling themselves Americana or alt.country since then. In 2003, Rolling Stone ranked the album No. 117 on its 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.

Ball and Maness became country rock's Wrecking Crew, owing in a large part to their own Sweetheart participation.

"It was the first of a thing that was waiting to happen," reflects the former. "It had a profound influence on ushering in and moving along acceptance of an earthier kind of music that was opposite of the psychedelic crap. It made it all right to be folky and country. But it took awhile."

Maness joined Hillman's highly successful Eighties country act, the Desert Rose Band. Ball played with Johnny Cash, intersecting with Marty Stuart's five-year residency in the band. As bluegrass legend Lester Flatt's teen prodigy sideman, Stuart first heard Sweetheart through bandmate Roland White – Clarence's brother. He also observed Parsons' dissipation from a distance at a 1973 rock festival featuring Flatt.

"The Byrds had such an adventurous musical spirit," says Stuart. "It amazes me that generation after generation, decade after decade, this record will not go away. I've owned it on cassette, 8-track, vinyl, CD, re-releases of vinyl, re-releases of the CD with alternate tracks. It's just one of those things that shows the integrity of the music and the band."

The Sweetheart of the Rodeo 50th Anniversary tour serenades ACL Live at the Moody Theater on Saturday, Nov. 10.

Taking The Byrds 10 Steps Further: Tom Petty Graces The Sweetheart Tour

Besides Gram Parsons' spirit necessarily hanging over proceedings, another deceased rock & roll legend's essence joins the Sweetheart of the Rodeo 50th Anniversary tour nightly: Tom Petty.

Beginning with "American Girl" and "Listen to Her Heart," which rang with a Rickenbacker 12-string guitar, Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers weren't just big on Bob Dylan and early Rolling Stones. They were clearly sons of the Byrds. Roger McGuinn never forgot the first time he heard "American Girl."

"I said, 'When did I record that?'" McGuinn laughed to PhillyVoice contributor Ed Condran upon Petty's death last year. "I was kidding, but the vocal style sounded just like me and then there was the Rickenbacker guitar, which I used. The vocal inflections were just like mine. I was told that a guy from Florida named Tom Petty wrote and sings the song, and I said that I had to meet him."

McGuinn had the band open some 1976 dates and covered "American Girl" on 1977's Thunderbyrd. Petty & the Heartbreakers also featured heavily on the Byrd boss's 1991 solo album, Back From Rio, featuring Petty/McGuinn single "King of the Hill," written in 1987 while all parties toured with Bob Dylan. Included on new multi-disc Petty set An American Treasure, the song is performed by McGuinn in a three-song tribute on this tour.

In fact, all involved in the tour were touched by Petty. Stuart's recent love letter to California country, Way Out West, was produced by Heartbreaker Mike, who graced the current Sweetheart trek by hopping onstage in L.A. for "American Girl," so the bandleader revs up what Hillman calls a "killer" acoustic "Running Down a Dream." Hillman, whose recent Bidin' My Time was produced by Petty, sings "Wildflowers."

"The album came out in the fall of 2017," says Hillman, "about a week before Tom died, and that was just devastating to me. I had gotten real close to Tom. He had taken this project on, and I wasn't even thinking about doing another record. He wanted to do it, and I said, 'You sure?' He said, 'Do you want me to?' I said, 'I'd love to work with you, but you haven't heard any of the songs I have.' He said, 'I'm not worried about it.' I said, 'I am!'

"We had a great relationship. We all have that special bond with Tom. Each of us does a song of Tom's at the end of the set, because Tom was so much a part of the family. He came out of Florida sounding like the Byrds, but he took it 10 steps further."