One, Two, Tres, Cuatro: Found a Job

If your job isn't what you love, then something isn't right

By Margaret Moser, Fri., Jan. 27, 2012

More Songs About Buildings and Food arrived in my mail at the Austin Sun sometime in 1978 and languished in the stacks until one day in early 1979 when my friend Dean Nichols pulled it out. The only thing I knew about it was watching Cindy Williams read a title from it on The Tonight Show With Johnny Carson.

"The Girls Want To Be With the Girls," the Laverne & Shirley star giggled to the talk show host. But Williams wasn't making fun of it. She was noting it with wonder. "The Girls Want To Be With the Girls." It wasn't typical of rock song titles, but then Talking Heads weren't making typical rock music.

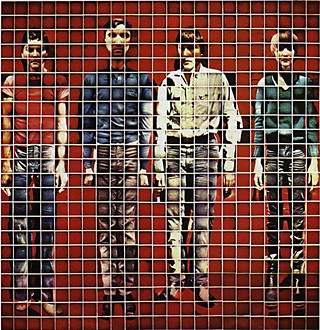

"This record is supposed to be great!" Dean oohed and ahhed. "That's so clever, taking all these Polaroids to make a photo of them. Let's play it."

I looked more closely. It was indeed clever. But Talking Heads were a New York band, a scene I hadn't had much interest in since the Velvet Underground. Blues dominated my life throughout the Seventies, with rock and country close behind, but I had a not-so-secret love of disco. Once Dean touched needle to vinyl, off the turntable came sounds that resembled rock & roll if Picasso had written the beat in bold, black strokes.

Songs peeled off one after another, layer after layer of this sheer, compelling sound. "Thank You for Sending Me an Angel," "With Our Love," "The Good Thing," "Warning Sign," "The Girls Want To Be With the Girls," and the last song on the first side, "Found a Job." That was the song.

Damn that television! What a bad picture!

Don't get upset. It's not a major disaster.

"There's nothing on tonight," he said. "I don't know what's the matter!"

"Nothing's ever on," she said. "So I don't know why you bother."

We've heard this little scene; we've heard it many times.

People fighting over little things and wasting precious time.

They might be better off, I think, the way it seems to me.

Making up their own shows which might be better than TV.

Well! More songs about angsty proto-yuppies? No, the lyrics crooked a finger and led on.

Judy's in the bedroom inventing situations.

Bob is on the street today, he's scouting up locations.

They've enlisted all their family.

They've enlisted all their friends.

It helped saved their relationship and made it work again.

OK, so Bob and Judy presaged reality TV, but that's not what David Byrne was writing about. He hadn't put the point on it until the last verse:

So think about this little scene. Apply it to you life.

If your work isn't what you love, then something isn't right.

I was jobless at the time. The kind of dissolute joblessness with little impetus to find anything better because work meant nothing but toiling for a paycheck so I could afford to go out and see music at Raul's and Soap Creek and the Armadillo and Antone's. Oh yeah, and pay rent and bills, though that was secondary to chasing a good time. Fuck work.

Dean Nichols died of AIDS around 1991; I feel badly that I don't remember the exact year. He had moved to San Francisco, where it seemed all the handsome young men went, and since that was what he wanted, he was home. I saw him one last time when he was quite ill. He wasn't very happy to see me since I'd shown up from Hawaii distinctly uninvited. He didn't want me to see him so wasted away, but I couldn't be dissuaded from putting my arms around my dear friend one more time.

In his prime, Dean was as strapping a symbol of golden gay youth as could be, good-looking enough to be appropriately cast in an Austin production of Norman ... Is That You? in the mid-Seventies. He was slutty and proud and smart to a fault, reeling off cruel comments precise as razor cuts. He once strode into my living room, put on More Songs About Buildings and Food, and plopped on the couch to compose a nasty letter to Edward Albee. They were supposed to meet the day before while the playwright was here visiting Austin, and Albee had stood him up. Dean scrawled a lengthy, crank-fueled tirade that involved then-Vice President Walter Mondale's wife Joan, a sale on lipstick at Walgreens, and a performance by pianist James Dick. All the while, Talking Heads crooned and hiccuped about warning signs and staying hungry.

We drove to the Driskill, and I waited in the car while Dean marched through its marbled columns and delivered his letter to the front desk, ensuring that Albee would receive it immediately. Alas, Dean arrived home hours later that night to find a message from Edward Albee, apologizing for missing their date and asking Dean to contact him. The message's time stamp in those days before cell phones was about two hours before the letter had been dropped at the Driskill.

Some weeks later, Dean and I sat in my living room listening to Talking Heads, still underemployed, the album practically imprinted in my DNA. David Byrne, Tina Weymouth, Chris Frantz, and Jerry Harrison made a record that truly meant something to me, songs of disaffection, yes, but more so songs of yearning. Not just discontent, but a desire for meaning within. At 25, being jobless felt shiftless, underscored by the need to make sense of my obsession with the meaning of music by writing about it. Dean felt pretty stupid about the whole thing with Edward Albee.

If your work isn't what you love, then something isn't right.

Damn! David Byrne was talking to us!

"Maybe I'll move to San Francisco," Dean said aloud, and not particularly to me.

And so he did.